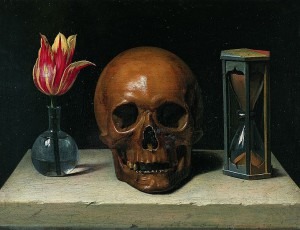

Leiden master, ca. 1635,

Vanitas still life with skull

The phrase comes from Ecclesiastes in the Bible: ‘Vanity of vanities, all is vanity’ where vanity refers to the ephemeral nature of our earthy pursuits and the futility of life on earth – heaven was always the better option.

In a typical Vanitas painting, there would be a skull, a reminder of the death to come; rotten fruit, symbolizing decay; and other images denoting the brevity of life: bubbles, cut flowers, smoke, or hourglasses. Musical instruments would also make an appearance due to their transitory sound. Food imagery was also popular: lemons and fish both being lovely to behold but bitter to taste.

Philippe de Champaigne:

Still-Life with a Skull (ca. 1671)

In music of the period, a similar remorsefulness about life also came into fashion. Composers wrote works such as laments, which was a song or poem expressing deep grief or mourning, or elegies, which were similar to laments but specifically about the death of a particular person.

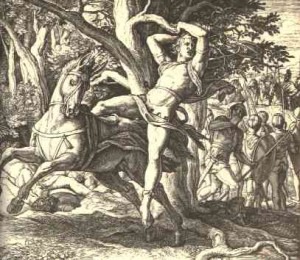

The best source, of course, for subjects, was the Bible, filled with reproaches about bad living or describing the death of seemingly favoured characters. One such person was Absalom, beloved third son of King David. He was rumoured to be the handsomest man in the kingdom. He was charming, was personally beautiful, and was famous for his long flowing hair. After living a charmed childhood, he tried to overthrow Kind David but was defeated and, in retreat, his beautiful long hair caught in the branches of a tree where he was killed. Here’s someone who truly died because of his vanity. A more excellent moral subject for a vanity song cannot be imagined, and this subject was taken up by a number of English madrigalists, including Orlando Gibbons (1583-1625), Robert Ramsey (1612-1644), Thomas Weelkes (d. 1623), and Thomas Tomkins (1572-1656). The text is very simple and comes from the second book of Samuel:

King David’s Lament

When David heard that Absalom was slain,

He went up to his chamber over the gate, and wept.

And thus he said: O my son Absalom,

Would God I had died for thee

Absalom my son.

Absalom

Whitacre: When David Heard

We’ve given you two very different recordings of King David’s Lament. Weelkes’ elegy, written after 1601, is a kind of sacred madrigal that becomes increasingly dissonant, as if we are in the person of King David as he realizes the extent of his loss.

Eric Whitacre’s modern version of ‘When David Heard’ becomes even more emotional, lingering at its climax on David’s heartfelt lament for his lost ambitious son.

Vanity led to Absalon’s fall and contemporary listeners could see in Weelkes’ setting the sorrow that self-focused vanity could cause.