Genoveva in the Forest Seclusion 1841 by Adrian Ludwig Richter

Robert Schumann (1810-1856) devoted his formative years primarily to literature. Already at the age of 13, he had published articles, written large anthologies of poetry, a five-act tragedy, and translated many Latin works into German. He even tried his hands at writing novels and dramas. He also became acquainted with the medieval legend “Genoveva” through Ludwig Tieck’s dramatized fairy tale. His youthful love of writing drama and poetry found an operatic outlet in 1847, when he commissioned the poet Robert Reinick to write a libretto based on Tieck’s play. However, when Schumann came across Friedrich Hebbel’s play, he asked Reinick to rewrite the libretto by fusing both plays.

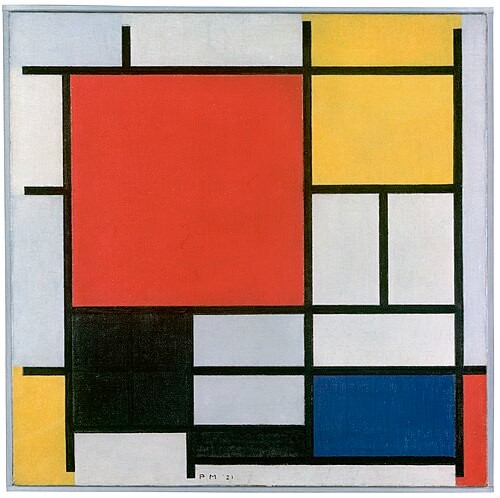

Schumann’s Genoveva

While Tieck focused on the legendary character of the Genoveva subject in a broadly designed historical picture orientated towards Shakespearian dramatic construction, Hebbel excluded all aspects relating to the story of the saint. Instead he concentrated on the explosive psychology of Genoveva’s antagonist Golo, whose development into a diabolical criminal is displayed with pitiless realism. Reinick refused Schumann’s request, and even Hebbel wanted nothing to do with the libretto. As such,

Schumann wrote the text for the opera himself, which inevitably lead to artistic disaster.

Robert Schumann: Genoveva, Op. 81 (Harald Stamm, bass; Alan Titus, baritone; Julia Faulkner, soprano; Keith Lewis, tenor; Renate Behle, soprano; Carl Schultz, vocals; Johann Tilli, bass; Hamburg State Opera Chorus; Hamburg Philharmonic State Orchestra; Gerd Albrecht, cond.)

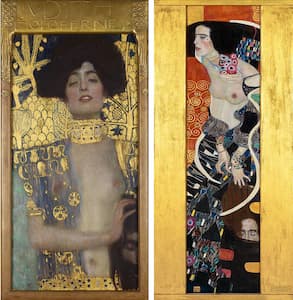

Gustav Klimt: Judith I & Judith II

Friedrich Hebbel’s theatrical plays added a new psychological dimension to drama by combining realistic presentation with theoretical and philosophical principles. He freely used Hegel’s concepts of history to dramatize conflicts in his historical tragedies. His first play “Judith” was written in 1840, and it made him famous throughout Germany. Based on the Book of Judith from Deuteronomy, Hebbel changes the political plot of the biblical story into a psychological investigation.

Siegfried Matthus

He imbues Judith with a sexuality and beauty that proves fatal to the men around her. She is left a virgin on her wedding night because her beauty renders her husband impotent, and she subconsciously exercises her repressed sexual desire, leading Holofernes to rape her so that she can subsequently behead him. “Holofernes prefigures the misogynist ideology of the fin-de-siecle, and while Judith resists the traditional female role she is given, she cannot transcend its restrictions.” Gustav Klimt painted two canvases with Judith as his focal point. While his first presentation focuses on the greatest degree of intensity and seduction, he abandons this magnetic fascination with sensuality in Judith II. Here she acquires sharper traits and a fierce expression, characteristics also brought into the foreground by the German composer Siegfried Matthus.

Siegfried Matthus: Judith, Holofernes’s Aria (Aris Argiris, baritone; Württembergische Philharmonie Reutlingen; Siegfried Matthus, cond.; Ola Rudner, cond.)

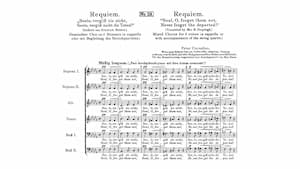

Peter Cornelius’ Requiem

Max Reger (1873-1916) considered his “Requiem” the most beautiful thing” he’s ever written. Dedicated to the “memory of the German heroes who fell in the 1914/15 War,” it does not rely on the common liturgical text, but he set the “Requiem” poem by Friedrich Hebbel. That particular poem had already served Peter Cornelius (1824-1874), who enjoyed a close friendship with the poet, as the foundation for one of his most personal, profound, and intense musical expression.

Soul, forget them not,

Soul, forget not the dead!

See, they hover around you,

Shuddering, abandoned.

And in the holy glow

which love stokes for the poor,

they breathe in relief and warm again

And enjoy for a last time

their dimming life.

Soul, forget them not,

Soul, forget not the dead!

See, they hover around you,

Shuddering, abandoned.

And if you coldly

shut yourself up to them, they stiffen

up into the deepest.

Then the storm of the night grips them,

which they, cramped together,

defied in the bosom of love.

It chases them impetuously

through an endless wasteland,

Where there is no more life,

only fight of unleashed forces

for renewed existence!

Soul, forget them not,

Soul, forget not the dead!

Peter Cornelius: Requiem (Seele, vergiss sie nicht) (Saarbrucken Chamber Choir; Georg Grun, cond.)

Max Reger’s Requiem

Under the immediate impact of WWI, Max Reger turned his attention to a setting of the liturgical Requiem in 1914. He quickly composed several sections and sent them to his friend Karl Straube for review. Straube was a respected church musician, organist and choral conductor who had taken up the position of organist at the Thomaskirche in Leipzig. Straube was highly critical of Reger’s effort, suggesting that the composer had failed to properly understand the Latin words. Reger was devastated and in order to break free from his crisis of confidence, turned to a 1912 motet for male chorus he had published as part of his Op. 83. That motet already made use of Hebbel’s Requiem poem. Reger now transferred Hebbel’s message, invested with a clear Christian dimension, into a setting for alto or baritone solo, chorus and orchestra. The work contains much lyrical beauty, “dramatic compactness, and economy of musical means.” Always combative, Reger once wrote, “If you want to know what I want and who I am, have a look at what I’ve written. If that doesn’t make you wiser then that’s not my fault.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Max Reger: Requiem, Op. 144b (Christoph Prégardien, tenor; Camerata Vocale Freiburg, choir; Basel Chamber Orchestra; Winifried Toll, cond.)