Gabriel Fauré’s mélodies represent a pinnacle of French art song, distinguished by their lyrical refinement, harmonic subtlety, and profound sensitivity to poetic texts. Fauré’s vocal compositions number over 100, and they demonstrate a melodic inventiveness that balances emotional expressivity with structural economy.

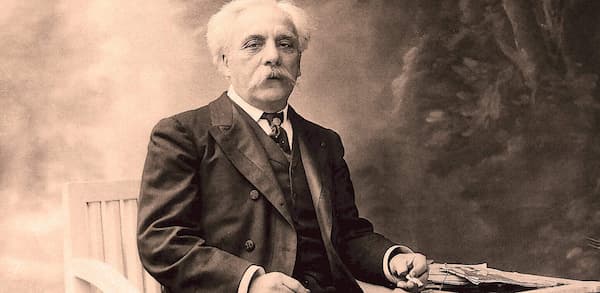

Gabriel Fauré

According to scholars, “this equilibrium reflects his ability to convey profound sentiment within tightly controlled musical frameworks,” avoiding the excesses of Romantic exuberance while maintaining a deeply affecting lyricism.

His structural economy is evident in his harmonic language, which often employs subtle modulations and modal mixtures to underscore emotional nuances without disrupting the melodic flow. The use of pivot chords and understated chromaticism “allows for expressive flexibility within a cohesive tonal framework.”

Prioritising suggestion over declaration, Fauré’s melodies achieve their emotional impact through the precision of their means, not through grandiose gestures. He was able to distill complex emotions into concise and carefully crafted musical forms, creating songs that invite introspection.

Fauré crafted mélodies that are intimately tied to their literary sources and universally evocative. They reveal his mastery of vocal writing and his influence on later composers. To celebrate his birthday on 12 May, let’s sample ten of his most sublime melodies.

“Après un rêve” (Op. 7, No. 1)

Published in 1878 as part of Trois Mélodies, Op. 7, “Après un Rêve” reflects Fauré’s early attempt to establish himself in Parisian musical circles. This particular mélodie emerged in the context of French salon culture, where intimate and expressive music was performed for educated audiences.

The text was adapted by Romain Bussine from an anonymous Italian poem, and it evokes a dreamlike journey toward an ethereal light, only to end in the pain of awakening. This particular theme resonates with the Symbolist movement’s interest in the ephemeral and ineffable. The use of lies in the final line introduces a subtle ambiguity, as the speaker acknowledges the dream’s falsity yet still craves its illusion.

The universal desire to reclaim idealised moments is amplified by musical means in this famous setting. The lyrical and conjectural melody evokes the fluidity of a dream, while the harmonic language is both tonal and subtly chromatic. Fauré’s setting is a model of word painting, and the role of the piano is dialogic, reinforcing the text’s imagery. A scholar writes, “Après un Rêve is significant for its embodiment of Fauré’s early aesthetic, which prioritizes subtlety and refinement over dramatic excess.”

“Clair de lune” (Op. 46, No. 2)

Jean-Antoine Watteau: The Scale of Love

Gabriel Fauré’s setting of “Clair de Lune” dates from 1887, composed during a period of his growing recognition in Parisian musical circles. By that time, Fauré had established himself as a composer of intimate and refined works that prioritised poetic nuance and musical elegance.

Part of the Deux Mélodies, Op. 46, “Clair de Lune” reflects the aesthetic of the French fin-de-siècle, “with its fascination for delicate and evocative imagery and the emerging Symbolist movement, which sought to capture fleeting impressions and inner emotions.” The poetry is by Paul Verlaine and is inspired by the commedia dell’arte tradition and the paintings of Antoine Watteau. The poem juxtaposes playful, theatrical imagery with an undercurrent of melancholy, creating a serene yet sorrowful spell that bends beauty with longing.

“Clair de Lune” is one of Fauré’s most celebrated melodies, admired for its delicate balance of text and music and its evocation of Verlaine’s ethereal imagery. The setting explores the tension between surface gaiety and underlying melancholy, and it amplifies this duality by using delicate textures and chromatic harmonies to evoke both the playful dance and the poignant atmosphere.

“En sourdine” (Op. 58, No. 2)

Frédéric Bazille : Portrait de Verlaine

Composed in 1891, “En sourdine” once again uses poetry by Paul Verlaine. Part of the Cinq melodies, composed during and after a trip to Venice, Fauré had refined his distinctive style, known for its harmonic subtlety, melodic fluidity, and a deep affinity for poetry. Fauré’s immersion into Verlaine’s Symbolist poetry and his exploration of refined and atmospheric textures created a masterful mélodie of hushed intimacy and transcendent longing.

Fauré focuses primarily on the visual imagery, creating a dimly lit and subdued atmosphere. He infuses the quiet environment with a gentle breeze of arpeggiated figuration that wanders through his entire setting. For scholars, Fauré’s choices of tonalities “convey comfort and calm intimacy, and the trust and reciprocation between man and woman…”

A cornerstone of the French arts song repertoire, “En sourdine” exemplifies Fauré’s ability to translate Symbolist poetry into a musical language of understated elegance and emotional depth. Its introspective tone aligns with the Symbolist fascination of the inner experience. The Venetian inspiration adds a layer of cultural context, evoking the city’s serene and reflective ambience.

“Chanson d’amour” (Op. 27, No. 1)

Armand Silvestre

This joyful and ardent love song dates from 1882 and sets a poem by Armand Silvestre. The poem is a passionate declaration of love, celebrating the physical and spiritual qualities of the beloved. The tone is celebratory yet intense, with the repeated “J’aime” creating a rhythmic pulse that drives the text forward.

Fauré’s setting amplifies this ardour through vibrant melodies and dynamic contrasts, while subtly hinting at the tension implied “by the beloved’s wildness.” The vocal melody is lyrical and declamatory, with the ascending phrases reflecting the speaker’s passionate declarations. Fauré’s harmonic language is tonally clear but subtly enriched with chromatic inflexions.

The piano accompaniment creates a lively and supportive texture that drives the song’s momentum. It is a significant early work in Fauré’s mélodie catalogue, showcasing his ability to craft emotionally direct songs within the constraints of the salon repertoire. By emphasising lyrical expressivity and textual clarity over dramatic narrative, Fauré also contributed to a genre distinct from the German lied.

“Automne” (Op. 18, No. 3)

Also dating from the early stages of Fauré’s career, and once again based on poetry by Armand Silvestre, “Automne” conveys deep emotion within a concise and accessible form. Its melancholic tone and evocative text-setting distinguish it from the more exuberant songs of the same period.

The poetry laments lost youth, happiness, and vitality by using autumn as a metaphor for decline. The repeated imagery of flowing water, weeping wind, and falling leaves reinforces the theme of inexorable loss, while the direct address in the final stanza personalises the season as both a mirror and a force of destruction.

Fauré’s setting is a model of word painting and emotional alignment. A descending melody and minor harmonies dominate the first verse, while a trembling melody underscores the speaker’s regret in the second. The dynamic climax in the third verse reflects the speaker’s confrontation with loss, and the postlude evokes the leaf being carried away by the wind.

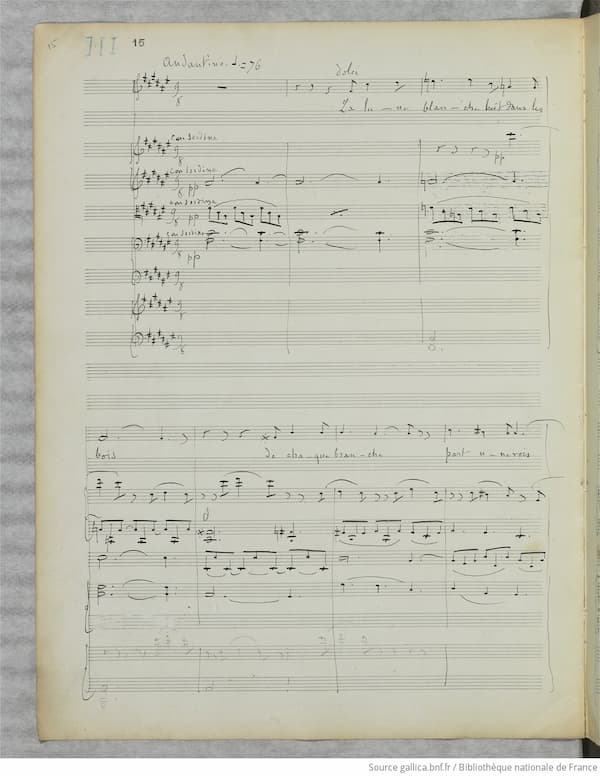

“La Lune blanche luit dans les bois” (Op. 61, No. 3)

Gabriel Fauré: La Lune blanche luit dans les bois

Gabriel Fauré composed “La Lune blanche” between 1892 and 1894, when he was at the height of his creative powers and increasingly recognised as a leading French composer.

This is the third of nine songs in his La Bonne Chanson collection. The entire cycle is based on Verlaine’s poetry collection of the same name.

The poem paints a tranquil and moonlit scene in a forest, with the speaker addressing the beloved, inviting them to dream of peace and tenderness. Verlaine’s Symbolist imagery creates a delicate, almost mystical atmosphere emphasising sensory impressions and emotional intimacy over narrative.

“La Lune blanche” is a standout mélodie, admired for its luminous beauty and seamless integration of poetry and music. As part of the cycle, it contributes to a cohesive narrative of love and optimism, yet it can stand alone as a miniature masterpiece of Symbolist evocation. As a pinnacle of Fauré’s mature style, it exemplifies the composer’s ability to translate Symbolist poetry into a musical language of luminous beauty and emotional depth.

“Mandoline” (Op. 58, No. 1)

“Mandoline” from Cinq mélodies de Venise, is a quintessential Fauré mélodie blending Verlaine’s poetry with a musical language of playful elegance and subtle charm. The poetry creates a whimsical and theatrical scene reminiscent of Watteau’s paintings, with serenaders and their listeners engaging in flirtatious and superficial exchanges under a moonlit, pastoral setting.

Verlaine evokes a timeless, almost artificial world of courtship, where joy and elegance mask an undercurrent of fleeting pleasure. Fauré’s lyrical and buoyant melody, cast in playful phrases, mirrors the poem’s light-hearted banter, while the harmony creates a balance between pastoral brightness and Symbolist ambiguity.

Unsurprisingly, the piano accompaniment is reminiscent of a mandolin, but as the singer is acting as a narrator rather than a character in the scene, Fauré’s setting implies a certain degree of emotional separation from the text. As Charles Koechlin writes, “Fauré’s music does not adapt itself to its subject, but it constitutes the essence of it; a magic mirror, his music becomes the subject itself.”

“Prison” (Op. 83, No. 1)

The mid-1890s were a time of personal and artistic transition, marked by the end of his engagement to Marianne Viardot. “Prison” reflects Fauré’s fascination with Verlaine’s introspective and melancholic verse, as well as his evolving musical style that combined tonal clarity with increasing chromatic complexity.

Composed shortly after “La Bonne Chanson,” its sombre tone contrasts with the cycle’s optimism, showcasing Fauré’s ability to adapt this music to varied emotional landscapes. The poem is a poignant reflection on confinement, contrasting the serene beauty of the external world with the speaker’s inner turmoil and regret.

The emotional arc of the poem is amplified by stark harmonies and a restrained vocal line. Through-composed, each of the four stanzas sets distinct musical material that reflects the poem’s emotional progressions. Avoiding strophic repetition to emphasise the text’s evolving mood, Fauré employs recurring motifs in the piano to provide unity.

“Au bord de l’eau” (Op. 8, No. 1)

Fauré composed “Au bord de l’eau” in 1875, having recently returned from military service in the Franco-Prussian War. It sets a poem by Sully Prudhomme, a French poet and the first recipient of the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1901. Known for his introspective and sentimental verse, the poem depicts two lovers sitting by a flowing stream, lost in a shared reverie.

It is a significant early mélodie in Fauré’s oeuvre, detailing his ability to craft lyrical and emotionally resonant songs within the accessible framework of the salon repertoire. Fauré writes a lyrical and flowing melody, gently arching, that mirrors the poem’s serene imagery. The harmony, balancing tonality with chromatic inflexions, creates an equilibrium between melancholy and warmth to complement the poem’s mood.

The song’s enduring popularity in vocal recitals, its frequent inclusion in pedagogical repertoires, and its arrangements for instruments like cello and piano highlight its timeless appeal and technical suitability for developing singers. As one of Fauré’s first published mélodies, it marks the beginning of his “lifelong contribution to the French art song tradition.”

L’Horizon chimérique (Op. 118)

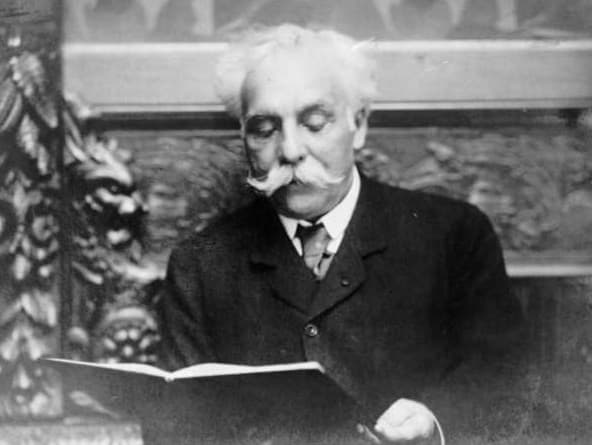

Gabriel Fauré, 1907

Gabriel Fauré composed L’Horizon chimérique, Op. 118, in the autumn of 1921, during the final years of his life. It was a period of reflection, marked by stylistic economy, harmonic daring, and contemplative intensity.

As a scholar writes, in “L’Horizon chimérique” Fauré blended a lifelong refinement with a forward-looking harmonic language.” The cycle’s maritime themes originate from the poetry collection by Jean de La Ville de Mirmont, a young Bordeaux poet who died in the first year of World War I. Fauré selected four poems, each evoking the sea, ships, and the lure of the unattainable horizon.

“L’Horizon chimérique” is a landmark in Fauré’s oeuvre, representing his final contribution to the mélodie genre and showcasing his late style’s harmonic innovation and emotional depth. Blending tonal and modal elements, Fauré creates a harmonic language that is both innovative and evocative. It underscores Fauré’s contribution to the mélodie as a genre distinct from the German lied, emphasising poetic imagery and atmospheric evocation over narrative drama.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter