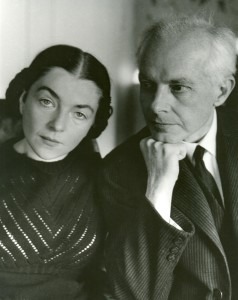

Béla Bartók had always been interested in young girls. His first wife Márta was only sixteen when they married, and he did have an extramarital affair with the fifteen-year-old poetess Klára. Bartók also vigorously but unsuccessfully pursued the young violinist Jelly d’Aranyi, grandniece of Joseph Joachim. But when he felt a strong attraction towards Ditta Pásztory, a gifted student in his Academy piano class, his marriage to Márta Ziegler came to an abrupt end. Predictably, Ditta was only 19 and Bartók 42 when they married on 28 August 1923. A fellow student relates the circumstances of this whirlwind romance and marriage. “Like myself, Ditta was a piano pupil of Bartók’s. Her lesson was the last of the day and one evening Bartók asked to walk her home. He said nothing at all until they reached her door when, without warning, he asked her to marry him. He gave her three days to make up her mind. She was totally flabbergasted but very proud of the invitation so she agreed. Somehow he acquired a special license, which enabled them to be married within one week.”

Béla Bartók had always been interested in young girls. His first wife Márta was only sixteen when they married, and he did have an extramarital affair with the fifteen-year-old poetess Klára. Bartók also vigorously but unsuccessfully pursued the young violinist Jelly d’Aranyi, grandniece of Joseph Joachim. But when he felt a strong attraction towards Ditta Pásztory, a gifted student in his Academy piano class, his marriage to Márta Ziegler came to an abrupt end. Predictably, Ditta was only 19 and Bartók 42 when they married on 28 August 1923. A fellow student relates the circumstances of this whirlwind romance and marriage. “Like myself, Ditta was a piano pupil of Bartók’s. Her lesson was the last of the day and one evening Bartók asked to walk her home. He said nothing at all until they reached her door when, without warning, he asked her to marry him. He gave her three days to make up her mind. She was totally flabbergasted but very proud of the invitation so she agreed. Somehow he acquired a special license, which enabled them to be married within one week.”

Edith (Ditta) Pásztory was the daughter of a piano teacher and a high school teacher. She studied piano at the Budapest Conservatory, and gained a diploma in 1921. By 1922, she enrolled at the Royal Academy of Music and became a student of Bartók’s. Ditta was an exceptional pianist, with a New York Times reviewer subsequently reporting, “Mme. Bartok sounds as if her hands are made of steel. Her technical accuracy is absolute – and the playing is cold as charity. Strangely enough, the result is neither cold nor off-putting…” Marrying Bartók, Ditta had to put her career as a pianist on hold. For one, she gave birth to their son Péter in 1924. In addition, as Bartók continued his previous routine of extensive traveling in the name of musical research, Ditta somehow had to fit into his busy professional schedule. She willingly accepted the fact that it would never be an equal partnership, focusing instead on providing an emotional haven for her husband.

Since Bartók was away from home with some frequency, he wrote a large number of letters to his wife. These letters cover a wide array of topics, ranging from ethnomusicology to nature and his impressions of foreign lands. They are always playful in tone, and reveal important dimensions of his personality and his interaction and reaction to people and situations. There is no doubt that his marriage to Ditta was the catalyst for a newly found professional optimism, as he writes on 21 June 1926: “Somehow I felt now, after a long time of no work, like a man who lies in bed over a long, long period, and finally tries to use his arms and legs, gets on his feet and takes one or two steps… Because, to be frank, recently I have felt so stupid, so dazed, so empty-headed that I have truly doubted whether I am able to write anything new at all anymore. All the tangled chaos that the musical periodicals vomit thick and fast about the music of today has come to weigh heavily on me: the watchwords linear, horizontal, vertical, objective, impersonal, polyphonic, homophonic, tonal, polytonal, atonal, and the rest; even if one does not concern one’s self with all of it, one still becomes quite dazed when they shout it in our ears so much… But now things are all right; you can imagine how pleased I am that at last there will be something new.”

Béla Bartók: Sonata for 2 Pianos and Percussion, BB115

For her husband and family Ditta had willingly sacrificed her own solo career. Béla was well aware of that fact, and eventually encouraged his wife to perform piano duets with him. The perfect vehicle for this artistic collaboration between husband and wife was the Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion, BB 115. Bartók had been planning to compose a work for piano and percussion. “Slowly, however,” he reports, “I have become convinced that one piano does not sufficiently balance the frequently very sharp sounds of the percussion.” The final version requires four performers; two pianists and two percussionists who play seven instruments between them. The work premiered, with Béla and Ditta at the keyboards, at the International Society for Contemporary Music on 16 January 1938 in Basel, Switzerland. It was enthusiastically received, and the couple used the work to introduce themselves to the American public in New York City’s Town Hall in 1940. Their American years were full of financial and medical hardships, and the couple last appeared on stage on 31 January 1943 at Carnegie Hall. Once Béla had passed away, Ditta returned to Budapest in 1946 and outlived her husband by 37 years.

You May Also Like

- Playing in Pairs: Bartók’s Concerto for Orchestra Béla Bartók’s Concerto for Orchestra challenges the educated listener on several fronts, starting with the title itself.

- Béla Bartók

“Competitions are for horses, not artists” Bartók wrote, “The Dance Suite is the intimate result of my researches and love for folk music.” -

Béla Bartók—Composer, Countryman and Collector Béla Bartók my father’s Hungarian countryman, is considered a composer of profound influence in the 20th century.

Béla Bartók—Composer, Countryman and Collector Béla Bartók my father’s Hungarian countryman, is considered a composer of profound influence in the 20th century. - Rebound from a Break Up

Béla Bartók and Márta Ziegler When Stefi Geyer rejected Béla Bartók’s proposal of marriage, the composer fell into a deep depression.

More Love

- Untangling Hearts

Klaus Mäkelä and Yuja Wang What happens when two brilliant musicians fall in love - and then fall apart? -

The Top Ten Loves of Franz Liszt’s Life Marie d'Agoult, Lola Montez, Marie Duplessis and more

The Top Ten Loves of Franz Liszt’s Life Marie d'Agoult, Lola Montez, Marie Duplessis and more - Mathilde Schoenberg and Richard Gerstl

Muse and Femme Fatale Did the love affair between Richard Gerstl and Mathilde Schoenberg served as a catalyst for Schoenberg's atonality? - Louis Spohr and Marianne Pfeiffer

Magic for Violin and Piano How did pianist Marianne Pfeiffer inspire a series of chamber music?