We think of musical notation as an object to be realized by a performer. As it sits on the page, there’s little there for someone who’s not musically educated to understand. You need the knowledge to read the notes.

And yet, musical notation can be a thing of art. There’s a German term for it: Augenmusik or Eye Music. Music that has visual messages along with the musical ones.

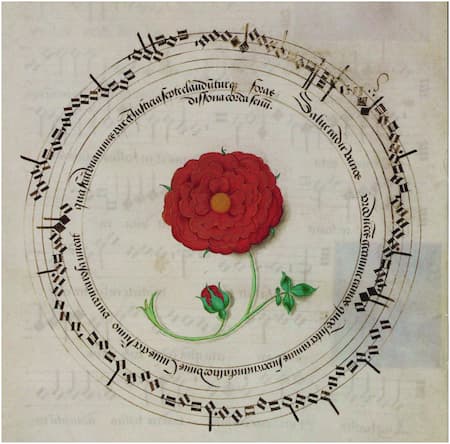

In the choirbook compiled in 1516 for King Henry VIII and Katherine of Aragon, the first wife of Henry VIII, the opening pages have a canon on the text ‘Salve radix’. The work is known as The Rose Canon because of the Tudor rose that sits in the middle of each of the encircling canons. The work is on two facing pages, the lower parts on the left page and the upper parts on the right-hand page. The music starts at about 2 o’clock on the page and the little pothook above the third note signals the second voice to start once the first voice reaches that note.

The Rose Canon (Contratenor parts) (British Library)

Richard Sampson: Salve Radix (Andrew Lawrence-King, harp; Alamire; Quintessential; David Skinner, cond.)

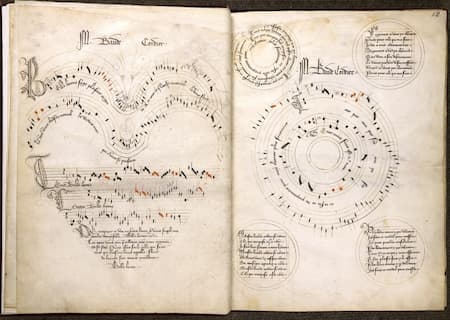

Two pages at the beginning of the Chantilly Codex have always grabbed readers’ attention because of their beauty.

They are both by the French composer Baude Cordier (ca 1380-ca1440) and each takes the idea from the text and creates an image. The first, “Tout par compas suy composés” (“With a compass was I composed”) sets the music in a circle in the middle and has addition circles at what might be considered the cardinal points on a compass.

Baude Cordier pages in the Chantilly Codex

Baude Cordier: Tout par compas suy composes (Ensemble Organum; Marcel Pérès, cond.)

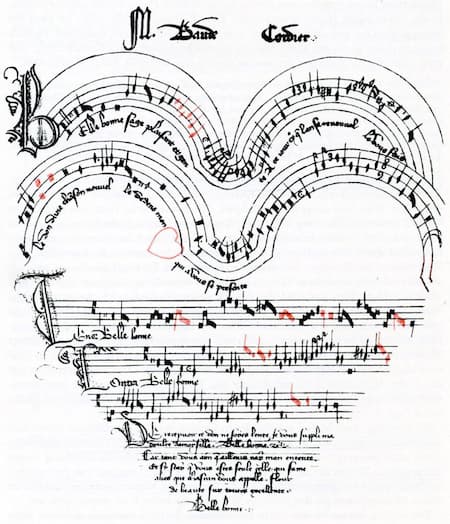

In Baude Cordier’s heart-shaped rondeau, Belle bonne sage plaisant, all the voices are on the same page: The top 2 lines are the top voice, the first horizontal line is the tenor, the second horizontal line is the Contratenor. Only the top voice has a complete text, the other two voices just have the first 2 words. Below the Contratenor lines are the rest of the poetic lines to be sung.

Baude Cordier: Belle Bonne (Chantilly Codex)

Baude Cordier: Belle bonne, sage, plaisant (Ensemble Organum; Marcel Pérès, cond).

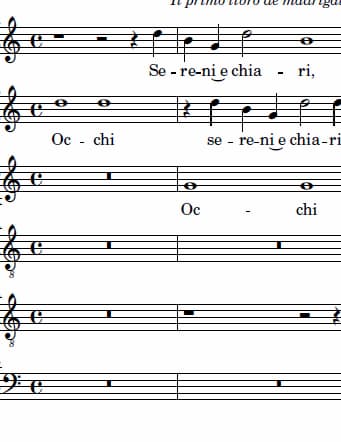

Moving into the Renaissance, we see fewer examples of this kind of notation, but composer still hid it in their music. For example, in his madrigal ‘Occhi sereni e chiari,’ (Eyes serene and clear) composer Luca Marenzio gives us the two long notes of the opening to represent eyes.

Score of Marenzio’s ‘Occhi sereni e chiari’

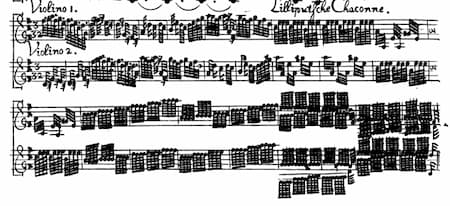

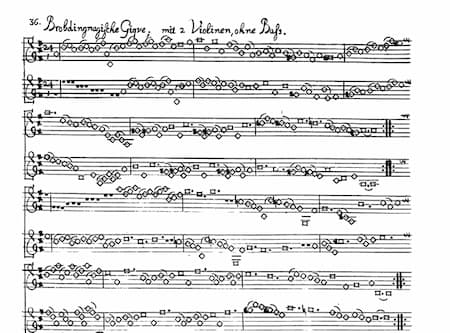

In his Gulliver Suite for 2 violins, Georg Philipp Telemann had a bit of fun in his score. For the two middle movements that portray the smallest and largest people that Gulliver met on his travels, we have the Lilliputsche Chaconne and the Brobdingnagische Gigue. Although these sound like a very brief (26 second) Chaconne and a longer length Gigue, the score tells a very different story.

What you can’t hear is that the Lilliputian chaconne is written in truly tiny notes (in length, not in size). The time signature is a very unusual one of 3/32, which reduces to the perfectly reasonable time signature of 3/4.

Lilliput Chaconne

Georg Philipp Telemann: Suite for 2 Violins, “Gulliver” – II. Lilliputsche Chaconne (Andrew Manze and Caroline Balding, violins)

On the other side of the scale, we have the Brobdingnags. In the Defoe novel, Gulliver estimates the Brobdingnags are 72 feet (22 m) tall, and normal-sized Gulliver is exhibited as a curiosity. In his music for the Brobdingnag Gigue, Telemann uses notes that are correspondingly large (whole notes in modern notation), but then gives them a highly unusual 24/1 time signature that would become a perfectly legitimate 12/8 gigue time signature.

Brobdingnag Gigue

Georg Philipp Telemann: Suite for 2 Violins, “Gulliver” – III. Brobdingnagische Gigue (Andrew Manze and Caroline Balding, violins)

The music doesn’t at all sound like it looks, and that’s the whole purpose of Augenmusik – it’s a private communication between the composer and the performer, with the listener left none the wiser for their discussion.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter