Scott Joplin was the pre-eminent composer of piano ragtime. In fact, one of his first and most popular pieces, the “Maple Leaf Rag,” became one of the genre’s most influential mega hits. Joplin considered the ragtime a form of classical music meant to be played in concert halls, and he did not appreciate its association with dance halls and honky-tonk bars. As a scholar writes, “Although he primarily worked in a popular idiom, Joplin strove for a classical excellence in his music and recognition as a composer of artistic merit.” Besides composing more than 40 ragtime pieces, he also created a ragtime ballet and wrote two operas. Even more reasons to take a closer look at the “King of Ragtime and Opera Pioneer” and his music.

Scott Joplin: “Maple Leaf Rag”

Early Experiences

There is a good bit of scholarly disagreement as to when and where Scott Joplin was actually born. We do know that he was the second of six children born to Giles Joplin, a former slave from North Carolina, and Florence Givens, a freeborn African-American woman from Kentucky. His birth date is frequently given as 24 November 1868, but that date has been recently challenged. As for his place of birth, both Texarkana, Arkansas, or Linden, Texas, have been proposed.

His father was a railroad labourer, and his mother a cleaner. Both were musically active, with his father playing the violin for plantation parties in North Carolina and his mother singing and playing the banjo. By the age of 7, young Scott was certainly taking piano lessons from a German immigrant musician. That encounter, according to a scholar, “seems to have played a significant role in the formation of his artistic aspirations.”

Scott Joplin: “Please say you will” (Raffaella Benetti, soprano; Giannantonio Mutto, piano)

Maple Leaf Rag

Painting of Scott Joplin

Joplin started working as a traveling musician and subsequently appeared with a minstrel company. He traveled far and wide with his vocal group, the “Texas Medley Quartette,” even performing at the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893. Joplin also started to issue his first publications, a couple of songs that were printed in Syracuse in 1895. After gaining further experience in a 12-piece ensemble, he attended music classes at a College in Sedalia, and performed as a pianist at the “Black 440 Club,” and the “Maple Leaf Club.”

Joplin published his first piano rag, “Original Rags,” in 1899 but was unhappy with the business arrangement whereby the publisher bought popular music outright for $25 dollars or less. With the aid of a lawyer, Joplin challenged this convention, and his next publication, the “Maple Leaf Rag,” turned out to be an extraordinary success. Collecting a percentage on every copy sold, the piece had sold half a million copies by 1909.

Scott Joplin: “Original Rags” (Alessandro Simonetto, piano)

Towards the Stage

In short succession, Joplin composed highly popular rags around the turn of the century, including the “Sunflower Slow Drag,” “The Easy Winners,” “The Strenuous Life,” and “The Entertainer.” Joplin enjoyed popular and limited commercial success as a composer of ragtime, but his ambition had always been to write for the lyric theatre. The Ragtime Dance scored for a ballet for dancers and a singer-narrator providing a theatrical glimpse of an African American Ball, was first staged in 1899 and published in 1902.

Joplin’s first attempt at opera followed the events surrounding the 1901 White House dinner hosted by President Theodore Roosevelt for the civil rights leader and educator Booker T. Washington. The event provoked vicious racist reactions from politicians and the Southern press, and no other African American was invited to dinner for almost thirty years.

Scott Joplin: “The Ragtime Dance” (arr. I. Perlman) (Itzhak Perlman, violin; André Previn, piano)

A Guest of Honor

A Guest of Honor advertising poster

The opera featured two acts and was modelled on the idea of grand opera. A copyright application was filed with the Library of Congress in 1903, but the application did not include a copy of the score. It was first informally presented in April 1903, and the performance had apparently taken place “in a large hall where they often gave dances at the Crawford’s Theatre in Louisiana.”

Joplin created the “Scott Joplin’s Ragtime Opera Company” of about 30 people to take A Guest of Honor for a national tour. It is unknown how many productions were staged, but on a tour stop, somebody stole the box office receipts. The endeavour quickly turned into a financial disaster, and scholars believe that the score for the opera was confiscated with Joplin’s belongings due to non-payment of his bills. Until today, no copy of the score of A Guest of Honor has surfaced, and it is considered lost.

Scott Joplin: “Sarah Dear” (Raffaella Benetti, soprano; Giannantonio Mutto, piano)

Treemonisha

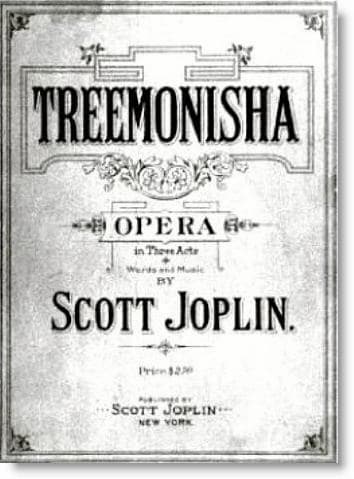

Treemonisha score cover

With his opera company disbanded, Joplin composed a number of notable rags, including “The Cascades” named after the attraction at the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904, and “The Chrysanthemum,” dedicated to his second wife Freddie Alexander. In addition, he was working on a new opera in three acts to his own libretto, titled Treemonisha. Joplin set the action of Treemonisha in a former slave community in an isolated forest near his childhood town of Texarkana in September 1884.

Ned (bass) and Monisha (mezzo-soprano) have a foundling daughter named after the tree under which she was discovered. They have been at great pains to give Treemonisha (soprano) a proper education, and she is taught to read by a white woman. As she has grown into an 18-year-old woman, she comes into conflict with the local witch doctors who cater to the superstitions of her people.

Scott Joplin: “Treemonisha” (Franca Mazzola, piano)

Plot and Music

Treemonisha is kidnapped by the witch doctors and about to be thrown into a wasps’ nest. However, she is rescued by her friend Remus (tenor) and brought home. At Treemonisha’s insistence the kidnappers are let off with a good talking to, and the community realises the value of education. The community also recognises that ignorance is a liability, and they elect her as their teacher and leader. In the end, she joins them in a celebratory dance, “A Real Slow Drag.”

In writing his libretto, Joplin followed the outlines of European opera and employed conventional arias, ensembles, and choruses. Joplin knew some works by Richard Wagner, and the themes of superstition and mysticism are well presented. It is certainly not a ragtime opera, “because Joplin employed the styles of ragtime and other black music sparingly, only using them to convey racial character and to celebrate the music of his childhood at the end of the 19th century.”

Scott Joplin: Treemonisha (arr. G. Schuller) – Overture (Houston Grand Opera Orchestra; Gunther Schuller, cond.)

Scott Joplin: Treemonisha (arr. G. Schuller) – Act I: The sacred tree (Betty Allen, mezzo-soprano; Houston Grand Opera Orchestra; Gunther Schuller, cond.)

Staging and Publishing

A Scott Joplin mural in Texarkana, Arkansas

Scott Joplin moved to New York City in 1907, hoping to find a producer and publisher for his new opera. Unable to find either, he published the score in piano-vocal format himself in 1911. It was favourably reviewed in the American Musician and Art Journal in 1911, but an actual staging could initially not be arranged. There was an informal run-through in 1911 and some excerpts performed in 1913 and 1915.

Eager to see his work on stage, Joplin invited a small audience to hear the opera in a rehearsal hall in Harlem. As a scholar writes, “Poorly staged and with only Joplin on piano accompaniment, it was a miserable failure to a public not ready for crude black musical forms—so different from the European grand opera of that time.” The audience, including potential backers, was indifferent and walked out, and as a result, Joplin suffered a breakdown.

Scott Joplin: Treemonisha (arr. G. Schuller) – Act II: Treemonisha in Peril (Raymond Bazemore, narrator; Dorceal Duckens, vocals; Ben Harney, vocals; Dwight Ransom, vocals; Houston Grand Opera Chorus; Houston Grand Opera Orchestra; Gunther Schuller, cond.)

Scott Joplin: Treemonisha (arr. G. Schuller) – Act II: Frolic of the Bears (Houston Grand Opera Orchestra; Gunther Schuller, cond.)

By abandoning commercial music in favour of art music, Joplin had ventured into a field that was essentially closed to African Americans. Today, Treemonisha occupies a special place in American history, “with its heroine a startlingly early voice for modern civil rights causes, notably the importance of education and knowledge of African American advancement.” In essence, it offered a celebration of literacy, learning, hard work, and community solidarity.”

A scholar describes the work as “ a fine opera, certainly more interesting than most operas then being written in the United States,” while suggesting that the composer was not a competent dramatist, “with the text not up to the quality of the music.” In the event, Treemonisha was quickly forgotten and not produced until the 1970s. Joplin’s orchestration has been lost, but three modern attempts have been produced by J. Anderson, William Bolcom and Gunther Schuller. It is celebrated today as a valuable record of rural black music from the late 19th century, recreated by a “skilled and sensitive participant.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter