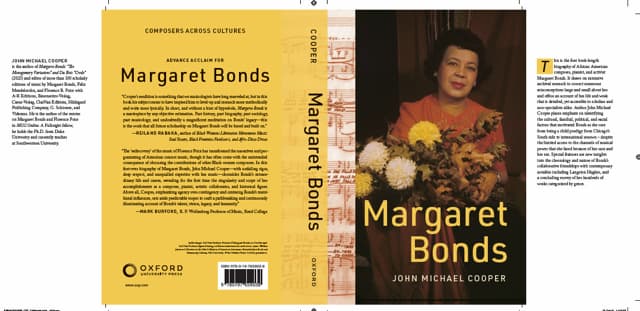

Dr. John Michael Cooper is a distinguished musicologist, scholar, and professor at Southwestern University in Georgetown, Texas. With a prolific career, he has made substantial contributions to music scholarship, including the publication of influential research and critical editions of works by composers like Florence B. Price and Margaret Bonds. Bonds (1913–1972), a prominent figure during the Civil Rights Movement, was an advocate for social justice and a passionate supporter of African-American artists. Dr. Cooper’s latest book, Margaret Bonds, is the culmination of years of archival research, offering a comprehensive biography of this groundbreaking composer. In our interview, Dr. Cooper shares his insights into the research process and his dedication to bringing Bonds’s legacy back to life.

Three Dream Portraits performed by Reginald Smith, Jr. (Baritone) and Llŷr Williams (Pianist)

How did you begin your research about Margaret Bonds? How long did it take?

Dr. John Michael Cooper

I fell in love with Margaret Bonds’s music in the late 1980s when I stumbled into a recital in a church in Tallahassee, Florida. The performance of Three Dream Portraits left me stunned—and frustrated. Despite my strong musical education, I had never encountered Bonds’s name or work. This powerful experience led me on a long journey to uncover more of her music, though I found that the biases of the publishing world had left much of her prolific output inaccessible. Over time, I pursued my formal work as a musicologist while also educating myself on African American perspectives and hoping someone would begin publishing Bonds’s compositions, but no new publications came. By the early 2010s, it became clear that her legacy required dedicated research and new scholarship. I started compiling an inventory of her works and, by 2018, considered writing a more accurate biography. When Oxford University Press invited me to write a full-length biography for their Composers Across Cultures series, I decided it was time to bring Bonds’s extraordinary life and music to light: I had to try my hand at it.

In many ways, this book has been decades in the making.

Bonds’s transposition of her “Revolutionary” (her word) setting of “You Can Tell the World”

What were the challenges of writing her biography?

The two main challenges were mastering the enormous and geographically far-flung body of primary sources that collectively trace Bonds’s life and then – in some ways even more difficult – allowing those primary sources to speak for themselves untainted by the many familiar conventional wisdoms about her life and work. Unfiltered, those sources told a story that was profoundly different than what’s commonly believed and said about Margaret Bonds and her music – and the new story was, if anything, even more inspiring than the familiar one.

And all that produced a third main challenge: how, in only about 350 pages (which is not a long biography), to simultaneously disabuse readers of the unfortunate false and misleading information they’ve been taught so far (“forget almost everything you thought you knew about Margaret Bonds”) while also telling the new, richer, and much more complex story that better represents who she was and how she pursued what she called her “Destiny” (upper-case D) over the course her exceedingly full fifty-nine years.

What surprised you the most when you were researching about her?

First, the conventional portrayal of her late California period (November 1967-1972) as a creative decline triggered by the death of Langston Hughes and fueled by alcoholism and depression is totally false – utterly unsubstantiated by any reliable source. Second, this conventional portrayal itself is basically an enactment of a widespread biographical trope that contradicts the facts of the matter. This trope hastens to attach women’s lives and women’s work to Significant Men – in this case, Langston Hughes – as early as possible, then grafts a portrait of inexorable decline or dissolution on those women if the Significant Men for any reason exit their lives. Generally speaking, that trope diminishes women’s agency in their own greatness and gives far more credit to the Significant Men than they actually deserve. More specifically, in the case of Bonds, it has created a misleading portrait of the relationship between her creative ascent and her friendship with Hughes, as well as inviting that abovementioned false understanding of what she did after his death and the significance of her work in those late years. If we set aside the trope and let her life and work speak for themselves, a new and, in many ways, surprising portrait of Margaret Bonds emerges. Finally, I’d like to emphasise that Bonds’s commitment to activism on behalf of African Americans comes at least as much from her father’s side of the family as from her mother’s – if not more so. Among other things, there is actually a remarkably direct and substantive connection, via her father and her nephew, the Rev. Hamilton T. Boswell, to U.S. Vice President Kamala Harris.

Credo performed by Conspirare, conducted by Craig Hella Johnson

In your opinion, what pieces of her writing expressed her personality and some of the moments of her life?

The obvious candidates here are the big social-justice masterpieces – the Credo and The Montgomery Variations – and her art songs on texts of Frost, Hughes, and Edna St. Vincent Millay, as well as her thirty-one known solo settings of spirituals, the choral arrangements of some of these, and the several choral spirituals. But those are only the “classical” side of Bonds’s creative imagination; to her, the line between “classical” and other music was basically fictitious and counterproductive: the popular songs (many of which have much in common with her “classical” music) also offer vivid portraits of her life and personality, and so do her many theatrical collaborations. Those songs range from an early popular song that she and her father co-wrote after Herbert Hoover (!) added an anti-lynching platform to his campaign for the U.S. presidency in 1928, through a number of blues songs that in some ways chronicle that huge stylistic changes in the blues as a genre from the 1930s to the early 1960s, to a set of late popular songs (my favorite is “Bunker Hill,” which focuses on the social issues and problems of gentrification in the titular Los Angeles neighbourhood). And the biggest challenges are posed by the stage collaborations, beginning with the mostly missing music to Romey and Julie (1937), through several big collaborations in the 1940s and 1950s, and ending with the nineteen-number musical Bitter Laurel (later retitled Lizzie), written in 1969-71 on the subject of the remarkable story of Elizabeth Keckley. We can’t really understand Margaret Bonds’s life without having a handle on the popular songs and theatrical works that collectively trace that life.

Dr. Cooper’s goal with this book is to bring Margaret Bonds’s legacy to a wider audience. He emphasises that Bonds’s story represents the brilliance of many marginalised composers whose contributions have been overshadowed by structures favouring white male composers. By embracing Bonds’s work, Dr. Cooper suggests, we not only deepen our understanding of 20th-century music but also open ourselves to a more inclusive and relevant view of today’s world.

Learn more about Dr. John Michael Cooper.

The book will be published on 28 January 2025, click here for more details.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter