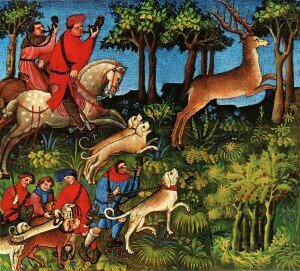

Evolution has given human beings four types of teeth, each with a specific function. Incisors cut the food, canines tear the food and molar and premolars crush the food. Given that kind of evolutionary structure, it seems rather reasonable to assume that the human being is omnivore. Besides crushing and grinding wild berries, we are also perfectly equipped to cut and tear flesh. As such, hunting for survival and nourishment is one of the fundamental and most ancient parts of human behavior. And just as fundamental is an extensive code of musical signals, which relates specifically to the process of hunting. It’s hardly surprising that composers throughout the centuries have utilized this particular musical symbolism of the outdoors.

Evolution has given human beings four types of teeth, each with a specific function. Incisors cut the food, canines tear the food and molar and premolars crush the food. Given that kind of evolutionary structure, it seems rather reasonable to assume that the human being is omnivore. Besides crushing and grinding wild berries, we are also perfectly equipped to cut and tear flesh. As such, hunting for survival and nourishment is one of the fundamental and most ancient parts of human behavior. And just as fundamental is an extensive code of musical signals, which relates specifically to the process of hunting. It’s hardly surprising that composers throughout the centuries have utilized this particular musical symbolism of the outdoors.

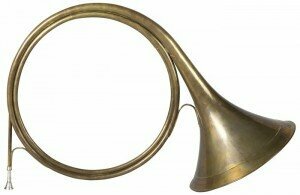

Hunting horn

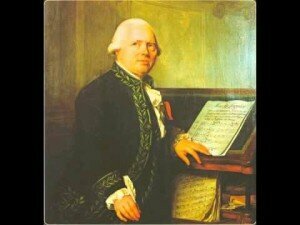

Gossec, François-Joseph: Symphony in D Major, Op. 13, No. 3 “La Chasse”

François-Joseph Gossec

Joseph Haydn: Symphony No. 73 in D major “La Chasse”

Mozart’s string quartet in B flat, K. 458 is nicknamed “The Hunt” and belongs to a group of six quartets composed in Vienna between December 1782 and January 1785. It appeared in print by Artaria and included an extensive dedication page. Mozart writes, “To my dear friend Haydn, a father who had resolved to send his children out into the great world took it to be his duty to confide them to the protection and guidance of a very celebrated Man, especially when the latter by good fortune was at the same time his best Friend. Here they are then, O great Man and dearest Friend, these six children of mine. They are, it is true, the fruit of a long and laborious endeavor, yet the hope inspired in me by several Friends that it may be at least partly compensated encourages me, and I flatter myself that this offspring will serve to afford me solace one day.” Neither Mozart nor Artaria called the K. 458 quartet “The Hunt.” Yet, for Mozart’s contemporaries the first movement seemingly evoked the “chasse” topic. With its 6/8 time signature and triadic melodies—making reference to the physical limitations of actual hunting horns—it clearly suggested not only a conscious effort to connect with the popular hunting trope, but was a compositional nod to Haydn’s hunting invocations as well.

Mozart’s string quartet in B flat, K. 458 is nicknamed “The Hunt” and belongs to a group of six quartets composed in Vienna between December 1782 and January 1785. It appeared in print by Artaria and included an extensive dedication page. Mozart writes, “To my dear friend Haydn, a father who had resolved to send his children out into the great world took it to be his duty to confide them to the protection and guidance of a very celebrated Man, especially when the latter by good fortune was at the same time his best Friend. Here they are then, O great Man and dearest Friend, these six children of mine. They are, it is true, the fruit of a long and laborious endeavor, yet the hope inspired in me by several Friends that it may be at least partly compensated encourages me, and I flatter myself that this offspring will serve to afford me solace one day.” Neither Mozart nor Artaria called the K. 458 quartet “The Hunt.” Yet, for Mozart’s contemporaries the first movement seemingly evoked the “chasse” topic. With its 6/8 time signature and triadic melodies—making reference to the physical limitations of actual hunting horns—it clearly suggested not only a conscious effort to connect with the popular hunting trope, but was a compositional nod to Haydn’s hunting invocations as well.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: String Quartet No. 17 “The Hunt”

Apparently, French critics appended the nickname “La Chasse” to Beethoven’s Sonata No. 18 in E-flat Major, Op. 31, No. 3. Although there is nothing on the documentary side to suggest that Beethoven was aiming for an evocation of a hunt, the nickname has stuck. In fact, Beethoven wasn’t in a particular bright and happy mood by 1801. What had begun as a slight ringing in his ears around 1789 had progressively turned to partial deafness. He even wrote his last will and testament in the form of a philosophical statement about his art and his physical disability. Eventually, Beethoven took heart and began to self-critically evaluate his compositions. He told his friend Werner Krumpholz, that he was dissatisfied with his earlier compositions, and that henceforth, “he would compose in a completely new way.” Overall, Op. 31, No. 3 emphasizes a much more lyrical and tender side of Beethoven’s craft. However, it is the extraordinary rush of energy flooding into the concluding movement, a highly energetic “Presto” that elicited the hunting nickname. Hunting horns blissfully join this extroverted gallop, and this sonata, which experimented with the customary arrangement of movements, concludes in an entire friendly and upbeat manner. I think the hunting references are a bit thin, but I’ll let you be the judge!

Apparently, French critics appended the nickname “La Chasse” to Beethoven’s Sonata No. 18 in E-flat Major, Op. 31, No. 3. Although there is nothing on the documentary side to suggest that Beethoven was aiming for an evocation of a hunt, the nickname has stuck. In fact, Beethoven wasn’t in a particular bright and happy mood by 1801. What had begun as a slight ringing in his ears around 1789 had progressively turned to partial deafness. He even wrote his last will and testament in the form of a philosophical statement about his art and his physical disability. Eventually, Beethoven took heart and began to self-critically evaluate his compositions. He told his friend Werner Krumpholz, that he was dissatisfied with his earlier compositions, and that henceforth, “he would compose in a completely new way.” Overall, Op. 31, No. 3 emphasizes a much more lyrical and tender side of Beethoven’s craft. However, it is the extraordinary rush of energy flooding into the concluding movement, a highly energetic “Presto” that elicited the hunting nickname. Hunting horns blissfully join this extroverted gallop, and this sonata, which experimented with the customary arrangement of movements, concludes in an entire friendly and upbeat manner. I think the hunting references are a bit thin, but I’ll let you be the judge!

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 18, Op. 31, No. 3