George Frideric Handel’s first season at the Royal Academy of Music was a huge success. By staging Rinaldo, Teseo, Amadigi, and Radamisto, he had quickly reached the commanding position he sought. In fact, Handel considered the aria “Ombra cara” from Radamisto his finest melody ever. The composer had been highly active in shaping the agenda of the Academy. He attended all meetings of the board, and he was closely involved in general administration and the engagement of singers. Handel also made decisions on scenery and staging and rehearsed the orchestra and the singers. He busily arranged the music of other composers and, in his spare time, found time to compose himself.

George Frideric Handel

The directorate of the Academy, however, did not want to put all their eggs into one basket and refused to exclusively back Handel. They were stockholders, after all, and the Academy was, above all, a business enterprise that had to be profitable. As such, they dispatched Lord Burlington to Italy to find an additional resident composer of stature. The choice fell on Giovanni Bononcini, and when he arrived in London in the autumn of 1720, the stage was set for a protracted opera war.

George Frideric Handel: Radamisto, HWV 12 (Ralf Popken, counter-tenor; Juliana Gondek, soprano; Lisa Saffer, soprano; Dana Hanchard, soprano; Monika Frimmer, soprano; Michael Dean, bass-baritone; Nicolas Cavallier, bass; Freiburg Baroque Orchestra; Nicholas McGegan, cond.)

Giovanni Bononcini

Giovanni Bononcini (1670-1747) was part of a distinguished musical family, and his father was a versatile composer and writer “whose fine cantatas and church music Handel had heard in Italy.” Padre Martini considered Bononcini’s brother Antonio Maria the most widely influential teacher of his age, and the two Bononcini were excellent instrumentalists who often served together in the same place and frequently wrote operas on the same libretti. The history of music did not have a particularly high opinion of Giovanni Bononcini, but this should not cloud the fact that he was a highly competent composer whose popularity initially did rival Handel’s. While in London, Bononcini produced eight operas, including the successful Astrato, Crispo, and Griselda. His simple and fluent melodic style and ability to write idiomatically for his singers made him popular with London audiences.

Giovanni Bononcini: Griselda (excerpts) (Lauris Elms, mezzo-soprano; Joan Sutherland, soprano; Monica Sinclair, contralto; Margreta Elkins, mezzo-soprano; Spiro Malas, bass; Ambrosian Singers; London Philharmonic Orchestra; Richard Bonynge, cond.)

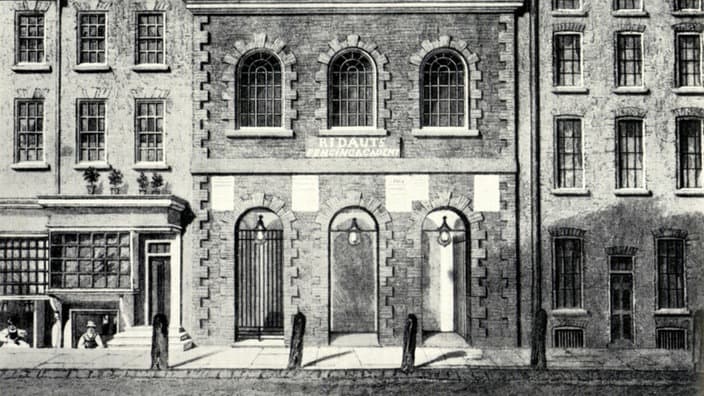

King’s Theatre in London, Haymarket

Initially, the directors of the Academy were delighted that Bononcini accepted the post of artistic co-regent with Handel. However, Bononcini’s success quickly engendered a heated divide emotionally enforced by self-appointed partisans. The directors soon wondered if that rivalry might hurt rather than help the business. Initially, the animosity between Handel and Bononcini wasn’t exclusively personal or professional; it was, above all, political. While the King steadfastly backed Handel, Bononcini was passionately supported by a group of noblemen. Handel was German and a former musician to the unpopular Hanoverian king, and when the Prince of Wales joined the Bononcini camp because of his hatred for his father, the war was on. The second season of the Academy opened on 19 November 1720 with Bononcini’s Astarto. The performance proved highly popular with the audience even though the music critic Charles Burney sharply wrote, “I could not discover that tenderness and pathos, for which Bononcini has been so celebrated, even by those who denied his invention and science.”

Giovanni Bononcini: Astarto (excerpts) (Antonio Abete, bass; Arcadia; Attilio Cremonesi, cond.)

For April 1721, the directors were looking to produce a new opera with an all-star cast. Paolo Antonio Rolli crafted the libretto for Muzio Scevola, dealing with the trials and tribulations of an ancient Roman mythical youth famous for his bravery. That in itself was rather unremarkable, but what made the project explosive was that the three acts of the libretto were to be set by three rival composers, Filippo Amadei, Bononcini, and Handel. Filippo Amadei (1665-1725) originally hailed from Rome, and he was a gifted cellist. He left for London in 1715 to take up an appointment with the Earl of Burlington, and he supposedly played two concerts a week for the Princess of Wales during the summer season. He became the principal cellist at the Royal Academy of Music, and he was considered a popular musician and a good arranger. It has been suggested that Amadei was a last-second substitute for Attilio Ariosti (1666-1729), who did not want to enter into a competition between Handel and Bononcini. Ariosti was a close personal friend of Bononcini, and he held the considerably younger Handel in high esteem. In the event, Amadei’s first act was considered poor, and a Handel biographer wrote, “Amadei’s music here is colorless, full of vain repetitions and aimless progression; the music has no life of its own and give none to the characters.”

Giovanni Bononcini: Muzio Scevola (excerpts) (John Ostendorf, bass-baritone; Erie Mills, soprano; Brewer Baroque Chamber Orchestra; Rudolph Palmer, cond.)

Senesino, 1720

With the Amadei appetizer out of the way, it was time to serve up the main course. For some, the competition between Bononcini and Handel looked very much like a gladiatorial combat. A critic wrote, “he who by the general suffrage should be allowed to have given the best proof of his abilities should be put into possession of the house.” And we all know the most celebrated and famous epigram written by John Byrom in 1725:

Some say, compar’d to Bononcini

That Mynheer Handel’s but a Ninny

Others aver, that he to Handel

Is scarcely fit to hold a Candle

Strange all this Difference should be

‘Twixt Tweedle-dum and Tweedle-dee!”

The assembled cast was “deemed the very finest of the age,” including the newly arrived alto castrato Senesino in the title role. Senesino was an outspoken ally of Bononcini, but the lyric bass Giuseppe Boschi had long been a favorite of Handel. The performance was interrupted by the announcement of the birth of the Duke of Cumberland to the Royal Family, but otherwise everything unfolded uneventfully. At the time, it was agreed that Bononcini’s music was judged to be fair, but Handel’s was far superior. Charles Burney wrote, the airs in Act II “are easy and natural, but no vigor of genius is discoverable.” As we know, Handel is a much better composer. Handel clearly had won this initial battle, but he had not yet won the war.

George Frideric Handel: Muzio Scevola, HWV 13 (Julianne Baird, soprano; Erie Mills, soprano; Andrea Matthews, soprano; D’Anna Fortunato, mezzo-soprano; Jennifer Lane, mezzo-soprano; Frederick Urrey, tenor; John Ostendorf, bass-baritone; Louise Schulman, violin; Myron Lutzke, cello; Edward Brewer, harpsichord; Brewer Baroque Chamber Orchestra; Rudolph Palmer, cond.)

Francesca Cuzzoni

The third season initially saw the revival of Handel’s Radamisto, and subsequently the composer presented his new opera Floridante. The plot was rather cumbersome, and the opera, although given fourteen times, was not really considered a success. Now that Bononcini had the advantage, he followed his lead with two new operas. Crispo was staged in January 1722, and Griselda a month later. Bononcini initially advertised his opera Crispo, which had been heard in Rome early on, by exclusive subscription to be performed in private houses. If 30 subscriptions were to be secured, Bononcini himself would personally perform on the cello. Bononcini wasn’t particularly honest, as despite his disclaimer, the opera was performed at the King’s Theatre with Senesino and Anastasia Robinson in the cast. In the event, both Crispo and Griselda were enthusiastically received, and Bononcini was highly successful away from the theatre as well. A much-admired collection of chamber duets was dedicated to the King, and it sold in numbers unheard of in those days. Round two clearly belonged to Bononcini.

Giovanni Bononcini: Crispo “Act III, Scene 5” (Lawrence Zazzo, counter-tenor; La Nuova Musica; David Bates, cond.)

Caricature of a performance of Handel’s Flavio, featuring Berenstadt on the far right, the soprano Francesca Cuzzoni in the centre and Senesino on the left.

Handel, however, had yet another ace up his sleeve. He quickly understood that it wasn’t simply a matter of composing another opera but that he needed a star. He found that star in the famed Italian soprano Francesca Cuzzoni (1699-1778), and she was engaged for the fourth season of the Academy. Her arrival was keenly anticipated in the press, and the London Journal reported on 27 October 1722, “Mrs. Cuzzoni is an extraordinary Italian Lady… she is expected daily.” The season opened with a revival of Muzio Scevola and Floridante, and on 12 January 1723, Handel’s newest opera Ottone premiered with the King present. Handel had created the role of “Teofane” specifically for Cuzzoni, but the prima donna apparently refused to sing the aria “Falsa imagine,” because it originally had been composed for Maddalena Salvai. A historian reports that having listened to her refusal, Handel replied, “Oh! Madame I know well that you are a real she-devil, but I hereby give you notice, me, that I am Beelzebub, the Chief of Devils.” Things got somewhat heated, and Handel might even have threatened to throw her out the window. In the event, the opera was a resounding success, and Cuzzoni “fixed her reputation as an expressive and pathetic singer.”

George Frideric Handel: Ottone, Act I (Drew Minter, counter-tenor; Lisa Saffer, soprano; Juliana Gondek, soprano; Patricia Spence, mezzo-soprano; Ralf Popken, counter-tenor; Michael Dean, bass-baritone; Freiburg Baroque Orchestra; Nicholas McGegan, cond.)

Handel’s success was a blow to Bononcini, who tried to counter with his opera Erminia. Critics compared it highly unfavorably against Ottone, and Handel quickly followed up his advantage with his opera Flavio. Handel completely finished off his rival in the fifth season by presenting Giulio Cesare with a cast headed by Senesino, Cuzzoni, and Boschi. Bononcini tried to counter with Calfurnia, but he understood that the war had been lost. He resigned from the artistic board of the Academy and gradually faded into the background. He retained his position as master of music in the household of the Duchess of Marlborough. In 1731 Bononcini was forced to leave England in disgrace as the Academy of Ancient Music denounced him for passing off a madrigal by Antonio Lotti as his own. Handel, in the meantime, raced from one success to the next. The Academy collapsed after nine seasons, partly due to extravagant expenditures. However, Handel contributed over half of the featured operas and established a new benchmark for Italian opera in England. And he certainly had outlasted and outperformed his rival Bononcini.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

George Frideric Handel: Giulio Cesare (Marie-Nicole Lemieux, contralto; Karina Gauvin, soprano; Romina Basso, mezzo-soprano; Emőke Baráth, soprano; Filippo Mineccia, counter-tenor; Johannes Weisser, baritone; Milena Storti, mezzo-soprano; Gianluca Buratto, bass; Il Complesso Barocco; Alan Curtis, cond.)