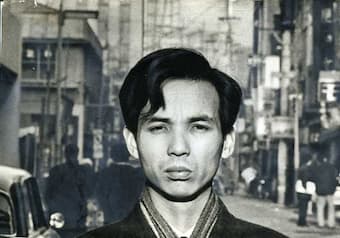

Tōru Takemitsu

When Emperor Hirohito ascended to the throne in 1927, he initiated a period known as the “Showa Restoration.” It advocated the revival of Shinto, and the so-called “State Shinto,” which had been developing over a period of time, came to dominate in the 1930s and 40s. “It glorified the emperor and traditional Japanese virtues to the exclusion of Western influences, which were perceived as greedy, individualistic, bourgeois, and assertive.” The ideals of the Japanese family-state and self-sacrifice in service of the nation “were given a missionary interpretation and applied to the modern world.” Prime minister Tanaka Giichi twice sent troops to China, and officers of the Imperial Japanese Army stationed in Manchuria resorted to assassinations to protect Japanese interests. Tōru Takemitsu was born on 8 October 1930 in the Hongō neighborhood of Tokyo to Takeo and Reiko Takemitsu. However, as an official of the Japanese government in southern Manchuria, Takeo Takemitsu quickly moved his family to Dalian, China.

Tōru Takemitsu: Distance de fee (Anne Akiko Meyers, violin; Jian Li, piano)

Growing up, the Takemitsu family enjoyed the privileged lifestyle as members of the expatriate community. A biographer writes, “Takeo Takemitsu had been able to indulge one of his favourite passions more frequently than might otherwise have been possible: the performance of jazz records from his vast personal collection. He had one or two other musical enthusiasms too, which it is just possible might have had some influence on the developing musical sensibilities of his son.” Growing up in the vast wilderness of Manchuria, Tōru exhibited a “kind of freedom and self-confidence that was not shared by Japanese who grew up in the much tighter, socially constrained circumstances of the Japanese Islands. In Manchuria, one could gaze out over vast terrain, with almost nothing blocking a view of the distant horizon—something that was virtually impossible in the densely populated and mountainous geography of Japan.” Takemitsu was sent back to Tokyo to live with an aunt and uncle, and he entered Fujimae Elementary School from 1937 to 1943, and the private Keika Middle School.

Growing up, the Takemitsu family enjoyed the privileged lifestyle as members of the expatriate community. A biographer writes, “Takeo Takemitsu had been able to indulge one of his favourite passions more frequently than might otherwise have been possible: the performance of jazz records from his vast personal collection. He had one or two other musical enthusiasms too, which it is just possible might have had some influence on the developing musical sensibilities of his son.” Growing up in the vast wilderness of Manchuria, Tōru exhibited a “kind of freedom and self-confidence that was not shared by Japanese who grew up in the much tighter, socially constrained circumstances of the Japanese Islands. In Manchuria, one could gaze out over vast terrain, with almost nothing blocking a view of the distant horizon—something that was virtually impossible in the densely populated and mountainous geography of Japan.” Takemitsu was sent back to Tokyo to live with an aunt and uncle, and he entered Fujimae Elementary School from 1937 to 1943, and the private Keika Middle School.

Tōru Takemitsu: Romance (Paul Crossley, piano)

“Frontier life had spoiled Tōru for conventional schooling. He was bored in school and followed paths of self-education far different from what their parents had envisioned.” He was supposed to follow in the footsteps of his father as a businessman but was initially drafted into the youth regiment of the Japanese army. His regiment was located at a remote storage depot in Saitama Prefecture. As such, he was spared the devastating firebombing of Tokyo in March and April of 1945. Tōru fell ill during the war years, and he would later recall two vivid memories from his military experience. “One day the company leader played a record of Josephine Baker or Lucienne Boyer singing a French chanson.” Jazz had been very popular in East Asia during the 1930s, but the Japanese government in 1939 banned it. For Takemitsu and his peers, “playing forbidden music behind the closed doors of a barracks backroom, struck emotionally on several levels.” In addition, he used to watch American bombers on their bombing raids on Tokyo, and he “conflated these glittering, dreamlike scenes with the silvery screens showing American movies before the war.”

Tōru Takemitsu: Lento in due movimenti, “II. Lento misteriosamente” (Takahiro Sonoda, piano)

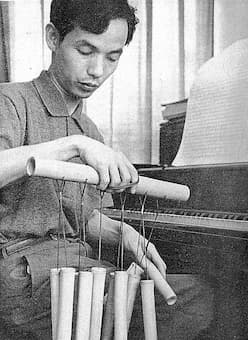

Takemitsu and Xenakis

Takemitsu never completed middle school but instead made money on the black market selling cigarettes and chewing gum, and later worked as a bus boy and an American PX in Yokohama. He read voraciously and listened constantly to radio broadcasts of all types of music. He was intensely inspired by American jazz, broadcast by the U.S. occupation forces in postwar Japan. And he was essentially self-taught in musical composition, and always claimed that his only real teacher had been Duke Ellington.

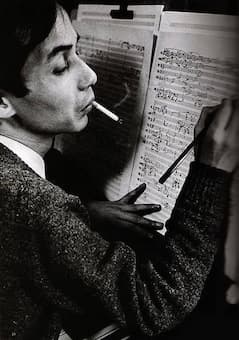

Takemitsu and Stockhausen

Takemitsu recalls that he started his search for his musical voice in the ruins after World War II. For the first time, he became aware of the “beauty of music from Western culture.” It was this particular realization that made him want to become a composer in the Western style. A scholar writes, “Takemitsu was among the first generation, in fact, caught in the confrontation between Japanese values and radical westernization.” In 1947 the “New Group of Composers” formed, and Yasuji Kiyose became Takemitsu’s first and only private composition teacher. Takemitsu was invited to join the group but quickly distanced himself. “I came to realize that the principle I have to fight is the Japanese nationalism. My music started by denying the direction that nationalism was taking. I experienced physical repulsion towards the sounds from Japanese vernacular, and had a strong feeling, without any reason, that we need to reject music similar to the politically charged wartime compositions.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Tōru Takemitsu: Pause ininterrompue (Masako Ohta, piano)