Herbert von Karajan is frequently hailed as the greatest living conductor of orchestral music. And while his conducting method is one of total authority and power, many critics have praised his emphasis on the perfection of sound, “note-perfect expressions of sheer, pure beauty.” For many music aficionados, colleagues, and critics, Karajan was “the greatest, the last great maestro. Karajan was the exception; no one can do it like he can. He is so egocentric, so clever, he uses all of his immense power to do the things he wants.”

Herbert von Karajan, 1938

And the music critic Martin Bernheimer called him “the last of the old-school European supermen of music… a genius on the podium.” He was a dedicated devotee of yoga and Zen Buddhism, and characteristically conducted scores completely from memory with his eyes tightly closed. For Karajan, this was not a pose of affection, but “it has to do with the gap between what you want and what you hear and how it becomes narrower.” Karajan explained, “when I was very young and started conducting, I had to train myself to listen to music as it came out because the orchestra of a provincial town was simply noncompetitive with what I had in my ear. This is the point where you begin, and then you take one step and then another, and the gap begins to narrow.”

Karajan Rehearses Mahler’s Symphony No. 5

Heribert Ritter von Karajan, born on 5 April 1908 in Salzburg, has always been tight-lipped about his formative years. As a biographer wrote, “his public is curious to know about his family. But he is not in the least inclined to satisfy such curiosity. In all the conversations that he recorded as part of the present biography, what he had to say about his family would fit on a single piece of paper.”

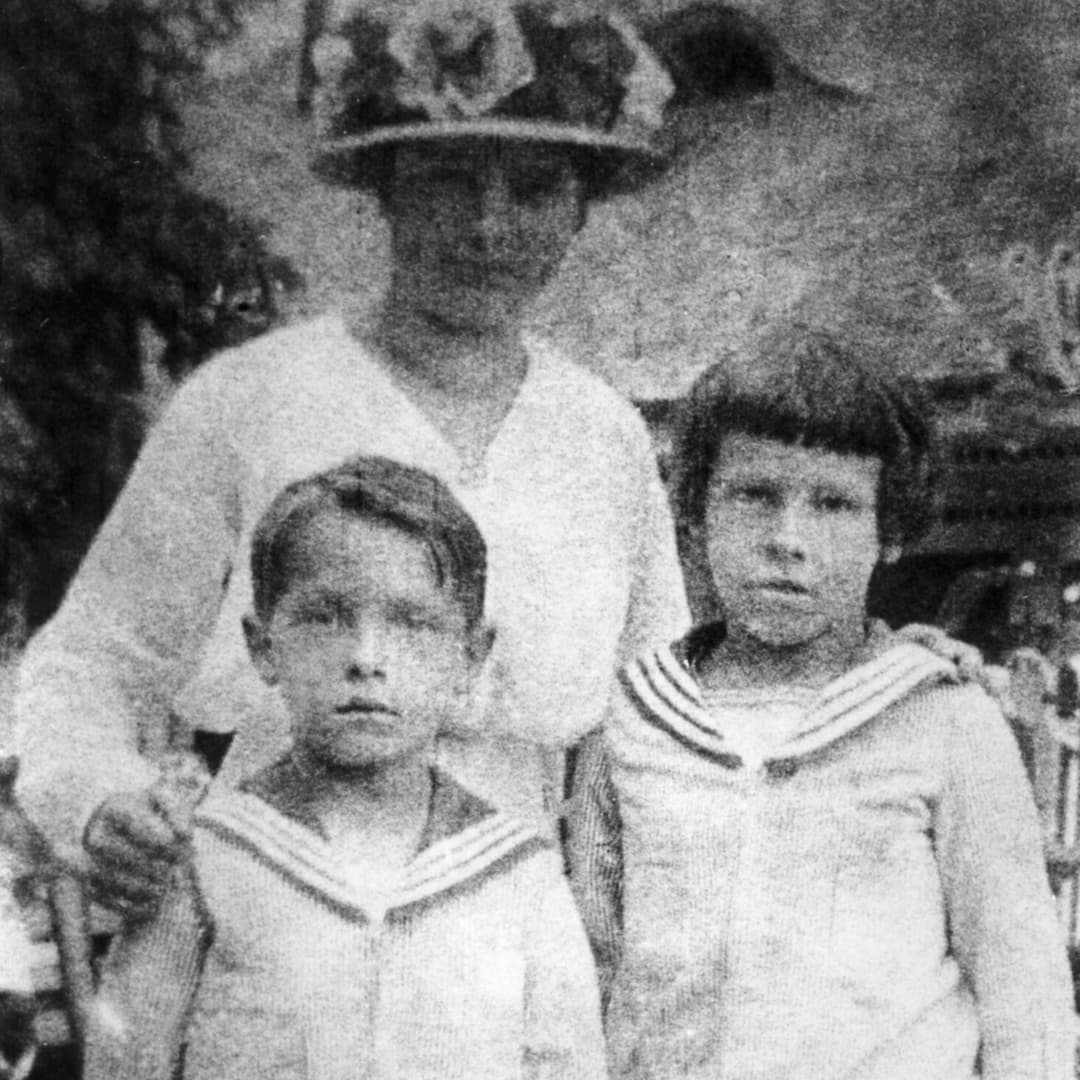

Herbert and Wolfgang Karajan

In fact, Karajan has never given a detailed account of his childhood. This has led to various speculations and theories, with one researcher claiming, “He was not the sort of man to guard sentimental memories or to harbor feelings of resentment.” Karajan clearly had a great number of ghosts in his closet, foremost among them his maintaining silence about his Nazi Party membership. In fact, Karajan joined the Nazi Party twice, first in Salzburg in 1933, and two years later he rejoined the party in Aachen. He subsequently insisted that his interest was “career advancement and survival rather than political conviction,” with Adolf Hitler personally appointing Karajan “state conductor” in Berlin. His enemies called him “SS Colonel von Karajan,” but the de-Nazification board immediately cleared him of any illegal activities, merely banning him from the concert halls for two years.

Karajan Conducts Bruckner’s Symphony No. 8 (excerpt)

The Karajans were of Greek ancestry, with his great-great-grandfather Geórgios Karajánnis leaving for Vienna in 1768 and eventually settling in Saxony. He established a clothing business with his brother, and both “were ennobled for their services by Frederick Augustus III. The conductor’s father Ernst von Karajan was a chief medical officer and senior consultant, and his mother Marta née Martha Kosmač, came from a Slovene background. Apparently, Heribert inherited from his father “a seriousness of purpose,” and he once suggested that his mother wanted him to go into banking. That, however, was never going to happen.

Herbert von Karajan, 1941

Karajan’s earliest memory was “hiding behind the curtains, jealously auditioning his brother’s piano lessons.” Wolfgang Karajan was a gifted pianist, but Heribert was extraordinarily talented. It was quickly discovered that he was a child prodigy at the piano. As he later recalled, “I was naturally under a lot of stress from my piano studies alongside my school work. I wasn’t just plonking away. I played in public every year. On the one hand, it isolated you; on the other hand, it gives you a satisfaction it would be very difficult to get from any other source.”

Karajan Conducts and Performs Mozart’s Concerto No. 21 in C Major, (excerpt)

Karajan practiced the piano for four hours every day, and he started attending classes at the Mozarteum in Salzburg in 1914. Within a couple of years, he was working with three eminent teachers, Franz Ledwinka (piano), Berhard Paumgartner (composition and chamber music), and Franz Sauer (harmony). And as the rising star of the Mozarteum, young Heribert made regular appearances in the yearly special Mozart Birthday Concerts. According to contemporary critics, Karajan played with great assurance both of manner and touch, “and a preoccupation with the beauty of sound born of an evidently precocious musical sensibility.”

Statue of Herbert von Karajan in Salzburg

Young Karajan also sang in various local church choirs in Salzburg, and he remembers “that choral singing has in fact accompanied me throughout my life.” Karajan claimed that Bernhard Paumgartner encouraged him to take up conduction, as he “detected his exceptional promise in that regard.” However, Karajan’s’ fascination with orchestral sound had already been identified by Ledwinka. In the event, Paumgartner took Heribert “along again and again to orchestral rehearsals and let him sit alongside him—‘So that you get an idea what conducting is like.’ And he also did his utmost to make sure that I eventually put it all to the test.” On the advice of Paumgartner, and on account of an inflamed tendon in one of his hands, Karajan turned to conducting, taking lessons with Alexander Wunderer and Franz Schalk at the Vienna Academy.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Karajan Conducts Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5