Building on the French mime tradition, traditionally done with white face and in white Pierrot dress, 19th-century mime Georges Wague expanded this to include song. Predating modern lipsynching by nearly a century, ‘cantomimes’ were created with a singer and instrumentalists off stage while on stage the mime pantomimed to the songs.

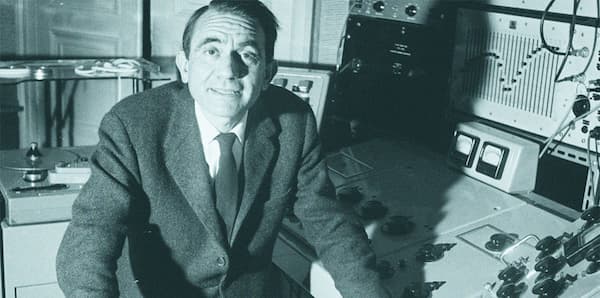

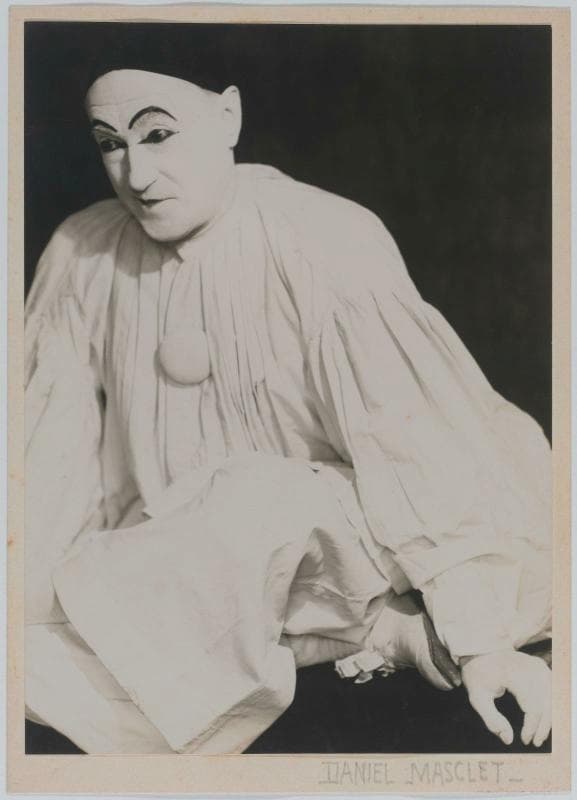

Daniel Masclet: Le Mime Georges Wague, 1923 (Centre Pompidou)

Created by mime artist Georges Wague (1874–1965) and the French singer Xavier Privas (1863–1927), cantomimes combined two French popular activities: chanson (song) and miming.

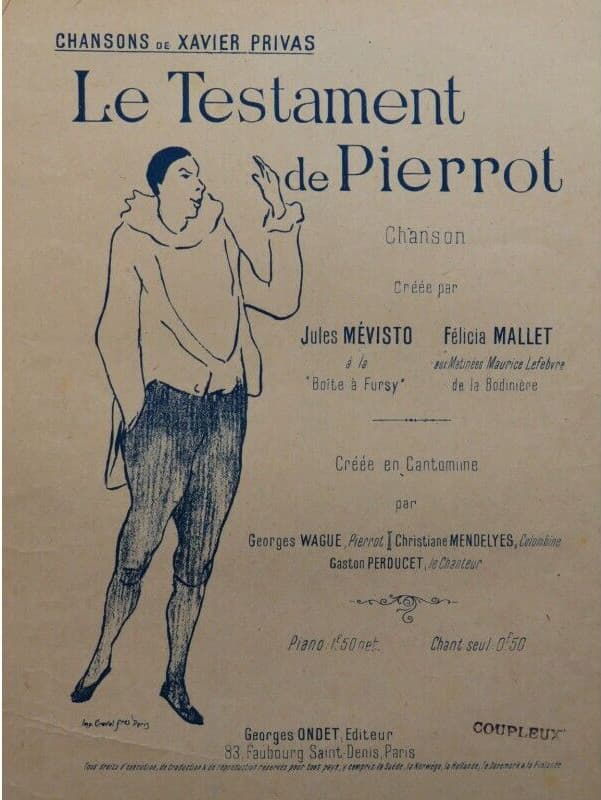

Their first common project was the 1893 cantomimes project that had its first staging in Paris at the Café Procope. The arts magazine La Plume sponsored soirées at Procope where Wague would perform. Wague was on stage while a singer and a pianist were off-stage. The mimes were usually based around the Pierrot character, including Noël de Pierrot (1894) and Le Testament de Pierrot (1895).

G. Charton / Xavier Privas: Comme ci, comme ca (Liane Augustin, soprano; Boheme Bar Trio)

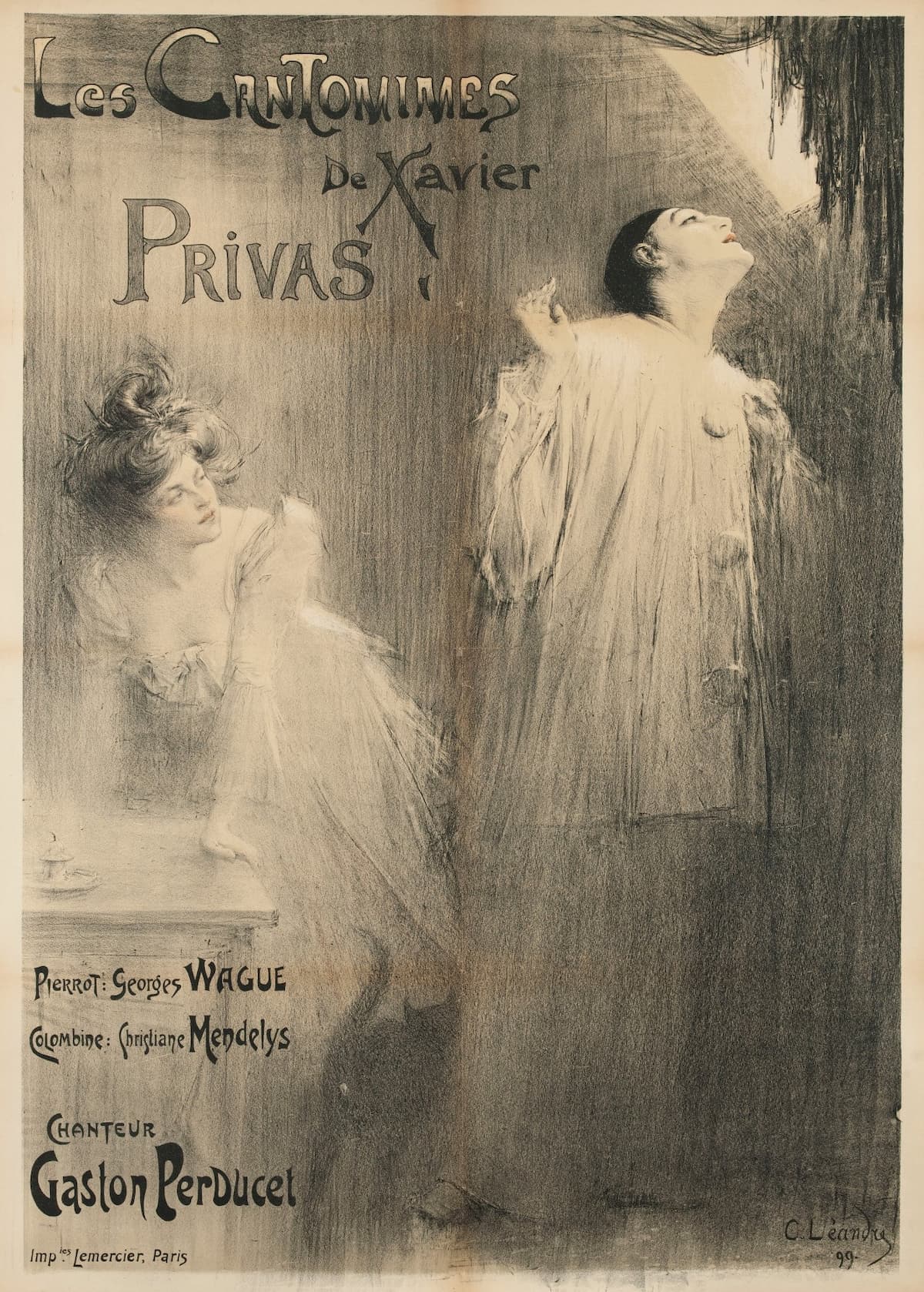

In this 1899 poster by Charles Léandre, Wague as Pierrot and mime Christiane Mendelys (later Wague’s wife) as Columbine are shown in Pierrot chante, where he’s singing to the moon. The poster itself was very famous – being referred to in news articles about cantomimes – and was in use until at least 1906.

Charles Léandre: Les Cantomimes de Xavier Privas, 1899

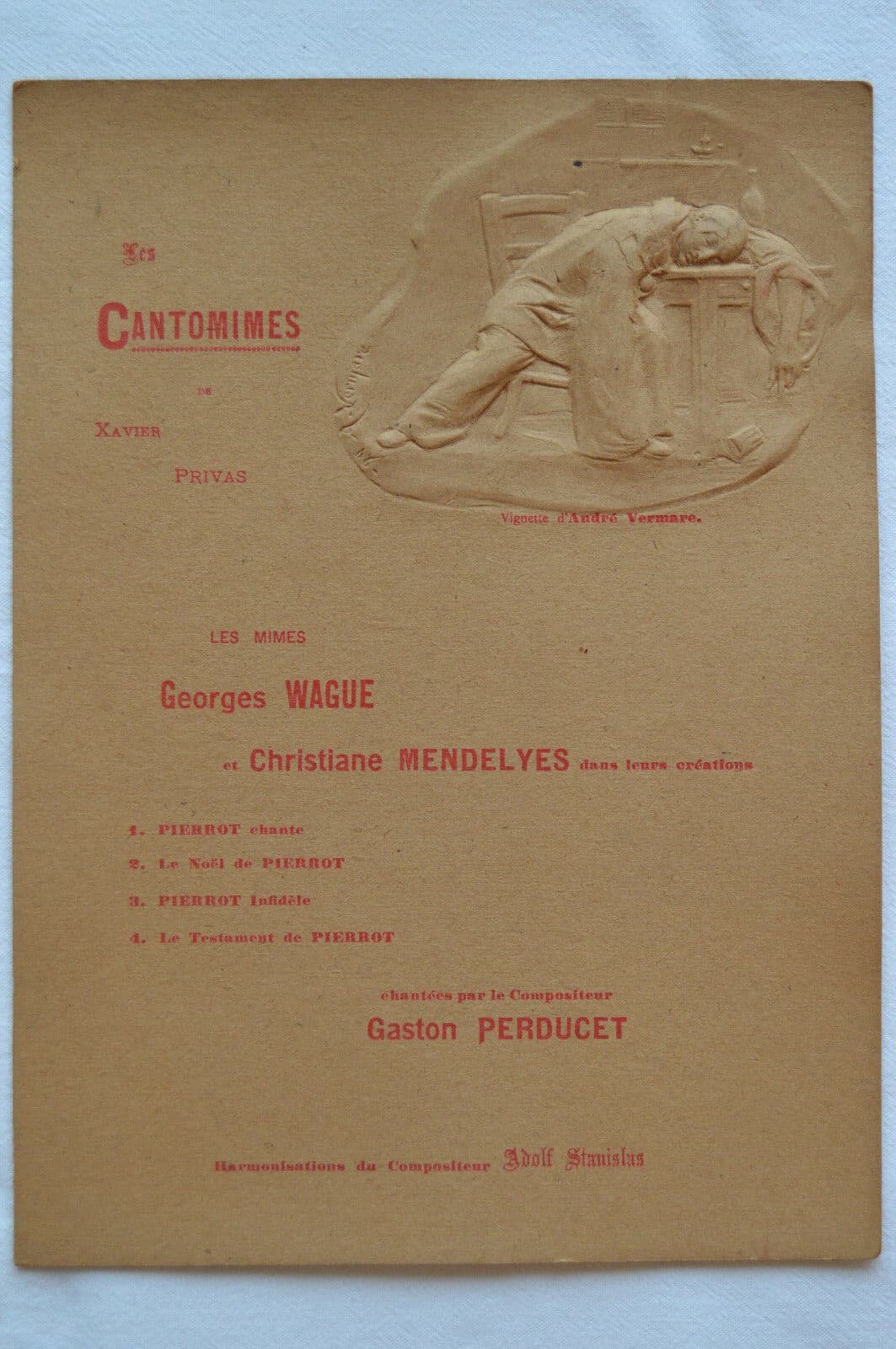

According to a notice in the L’echo de Rouen illustré, on 8 October 1899, the show included Pierrot chante!, Le Noël de Pierrot, Pierrot infidèle, and Le Testament de Pierrot. It also says that the melodies, written by Xavier Privas, were orchestrated by ‘the young composer Adolf Stanislas. As a note, in Privas’ published songs, he only gives the melodies and the words, not the harmonization. The songs, sung by Georges Perducet, would be sung from the orchestra pit, ‘while on stage, Pierrot and Colombine will translate the pretty stanzas of the master of the song with gestures and beautiful attitudes.

Xavier Privas: La ronde des heures

Cantomimes program, with Pierrot shown in a relief vignette by André Vermare

The storylines are simple. In Pierrot chante!, he sings passionately to Tanit, the moon, his coy departed muse. In Noël de Pierrot, the poor Pierrot serenades Colombine, promising his heart as a New Year’s gift. In Testament de Pierrot, the dying Pierrot bequeaths his debts to his creditors and his irony to wayfaring poets.

Privas: Le Testament de Pierrot (Paris: Georges Ondet, n.d.)

Wague’s influence on French mime tradition in his cantomimes was fundamental: he was creating a new genre of meme where states of feeling were represented through natural movement, something he developed from his teacher, Félicia Mallet. Where traditional miming translated ‘words through an arcane sign language of the body…’, coming from the philosophy developed by the mime Séverin, Wague strove for direct representation, seeking to express the ‘truth of human experience’ in his new, natural gestures.

Privas: La Révolte

Happichy: Séverin in Mendès’s Chand d’habits!, 1896 (New York Public Library Theatre CollectionO

Christine Mendelys’ contribution was just as powerful as Wague’s. She met Wague at the Paris Conservatoire, where she was studying mime under Félicia Mallet. The rise of the popularity of mime at the end of the 19th century met the incoming tourists for the 1900 Paris Exposition Universelle and flourished.

Wague and Mendelys

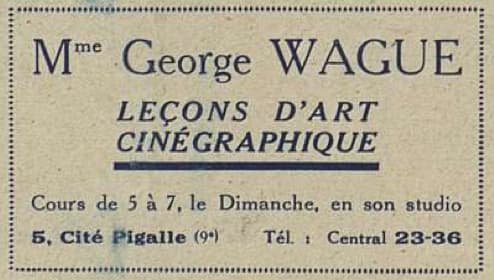

In the French press, we can find notices for her performances at the Théâtre des Mathurins, the Bodinière, the Gaîté-Montparnasse, the Théâtre des Capucines, the Théâtre d’Antin, the Théâtre Mondain, the Théâtre Rabelais, the Eiffel Tower theatre, the Théâtre Grévin, the Grand Guignol, the Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens, and the Théâtre de Montrouge. After cantomimes, she became an important part of the early French film industry, as an actress, screenwriter, and director for Gaumont. She was also a film critic, known for her incisive reviews that were based on her expertise in the industry. In 1920, she and Wague opened an acting school and film school in their Pigalle studio.

Ad for the Wague acting school, appearing Ciné pour tous, 1920

Wague attempted to copyright cantomime, but we can see other artists taking up the idea. January 1932 edition of Musical America notes that Louise Le Gai, known as a choreographer for opera companies in Philadelphia in the 1920s and early 1930s, had given a performance of Cantomimes at the Booth Theatre on 24 January. ‘…music ranging from a percussion accompaniment’ to music by ‘Chopin, MacDowell, and folk songs’ was used. She was assisted by Howard Blair, baritone, dancer, and pianist, with 3 pianists and a debut by Waldene Reese Johnson on violin. The New York Times review gave the program as ‘a series of sketches including an incident in the life of Chopin, a scene in an Egyptian tomb in 1500 B.C., and character scenes from other countries, including Africa, Spain, England, France, and Japan’ and closes with a stinging ‘The mixture of singing and dances with dramatic pantomime proves somewhat confusing to the audience. A program note stated that Miss Le Gai “represented no special school.” During the course of the evening, this statement proved entirely correct’.

Wague and Mendelys worked to free mime from the centuries-old commedia dell’arte traditions of Pierrot and Columbine. Once the two characters were freed from the stock characters and their fixed relationship, both male and female mimes could ‘expand the emotional power of movement and provide a great array of tensions between male and female bodies’.

Georges Wague embraces the author and actor Colette in L’Oiseau de Nuit (1911)

Both Wague and Mendelys were able to move out of mime and into film, clothed differently, as they brought their art a new medium.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter