Antonio Vivaldi’s operatic opportunities in Venice were rapidly drying up in 1739. As the famous letter from Charles de Brosse relates, “Vivaldi is an old man with a mania for composing. I have heard him boast of composing a concerto in all its parts more quickly than a copyist could write them down. To my great astonishment, I have found that he is not as well regarded as he deserves in these parts, where everything has to be fashionable, where his works have been heard for too long, and where last year’s music no longer brings in revenue.”

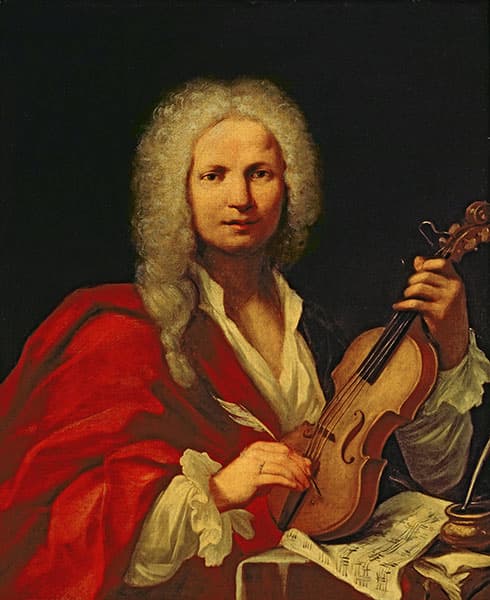

Portrait of Antonio Vivaldi

Despite the fickle nature of the Venetian public, Vivaldi had been a vastly successful composer, virtuoso and impresario for many years. His first opera was presented in 1726, but “now, even with all his energy and ability, he could no longer please them.”

Antonio Vivaldi: “La Stravaganza” No. 2, RV 279

Vivaldi’s Final Journey to Vienna

The reason why Vivaldi ventured on his final journey to Vienna at the age of 62 is still a matter of conjecture. Possibly, Charles VI had invited him, or he might originally have had a different destination in mind. It has been suggested that he might have been on his way to Dresden, where he had powerful friends, or to the home of his former patron Count Morzin in Bohemia.

In the event, the governors of the Pietà first disclosed knowledge of Vivaldi’s departure in a debated resolution on 29 April 1740. “It has been brought to our attention,” they write, “that our orchestra needs concertos for organ and other instruments to maintain its present reputation. Having heard also that Reverend Vivaldi is about to leave this capital city and has a certain quantity of concertos ready for sale, we shall be obliged to them.” In the end, they purchased 20 Vivaldi concertos.

Antonio Vivaldi: L’oracolo in Messenia, RV 726 (Julia Lezhneva, soprano; Vivica Genaux, mezzo-soprano; Ann Hallenberg, mezzo-soprano; Romina Basso, mezzo-soprano; Franziska Gottwald, alto; Magnus Staveland, tenor; Xavier Sabata, counter-tenor; Galante Europa; Fabio Biondi, cond.)

A historical marker in Wieden in Wien, Austria

Vivaldi probably was drawn to Vienna to stage operas, especially as he took up residence near the Kärntnertortheater. Shortly after his arrival in Vienna, however, Charles VI died, which left the composer without any royal protection or a steady source of income.

Vivaldi seemingly disappeared, but his presence in Vienna on 28 June 1741 can be confirmed by a receipt for the sale of an unspecified number of compositions to Antonio Vinciguerra, Count Collalto, a nobleman of Venetian origin whose main residence was at Brtnice in south-west Moravia. Vivaldi died in the night of 27/28 July 1741 in the house of the widow of a saddler named Waller. This particular house was demolished to make way for the new Ringstrasse in 1858, and part of the Hotel Sacher is currently built on part of the site.

Antonio Vivaldi: Violin Concerto in B-flat Major, RV 366 (Alberto Martini, violin; Accademia I Filarmonici)

The Funeral of Vivaldi

Karlskirche and Hospital Cemetery

The cause of death was stated to be an internal inflammation. The funeral took place at St. Stephen’s Cathedral, and the popular legend that the young Joseph Haydn, who was in the cathedral choir at the time, sang during Vivaldi’s funeral, is pure fiction. In fact, no music was performed, but contemporary witnesses report, “the funeral was accompanied by a small peal of bells, and the expenses were kept to the minimum.” Later on that day, Vivaldi was unceremoniously buried in the Hospital Cemetery next to the Karlskirche, on the present site of the Technical University in Vienna. In the event, Vivaldi was given an ordinary and simple burial, and not a pauper’s burial as is often reported.

Antonio Vivaldi: Salve Regina

It is true that Vivaldi had been enormously successful in his lifetime and must have earned a great deal of money. He might actually have been a very rich man. How then can we explain his great poverty towards the end of his life? A contemporary account suggests, “The abate D. Antonio Vivaldi, the incomparable violinist known as the red-haired priest, highly esteemed for his concertos and other compositions, earned at one time more than 50,000 ducats, but his inordinate extravagance caused him to die poor in Vienna.”

Scholars have discounted the charge of extravagance. “We know that Vivaldi talked of the cost of maintaining a household capable of taking care of his needs as an invalid, just as we know he was involved in operatic speculations as an impresario which may not have been uniformly successful, particularly in the later part of his life.”

Antonio Vivaldi: Mandolin Concerto in C Major, RV 425 (Bonifacio Bianchi, mandolin; I Solisti Veneti; Claudio Scimone, cond.)

Vivaldi’s Legacy

Antonio Vivaldi monument on Rooseveltplatz in Vienna

One thing is for sure, Vivaldi’s music completely disappeared from the public stage following his death, especially in Venice. He did remain in currency in Germany, although when his name was mentioned it was in a dismissive or patronizing way “and the judgment of his ability was harsh.”

Vivaldi enjoyed great popularity in England, with a distinguished Professor of Music at Oxford admitting certain faults of compositions, “…and yet, I think, Vivaldi has so much greater merit than the rest that he is worthy of some distinction. Admitting therefore the same kind of levity and manner to be in his compositions with those of Tessarini, yet an essential difference must still be allowed between the former and the latter since an original is certainly preferable to a servile, mean copy.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter