Completed in early 1826, Beethoven’s String Quartet Op. 130 premiered on 21 March 1826 as part of the concluding subscription concert by the Schuppanzigh Quartet.

Ludwig van Beethoven

The work immediately caused great puzzlement, as we read in a contemporary review, “The most recent quartet by Beethoven in B-flat, consisting of the following movements: a. Allegro moderato; b. Presto; c. Scherzo Andantino; d. Alla danza tedesca; e. Cavatina; f. Fuga. The first, third, and fifth movements are serious, gloomy, mystical, but also at times bizarre, rough, and capricious; the second and fourth full of mischief, good cheer, and roguishness. Here the great composer, who, particularly in his most recent works, has seldom known how to find appropriate limits, has expressed himself unusually briefly and convincingly.”

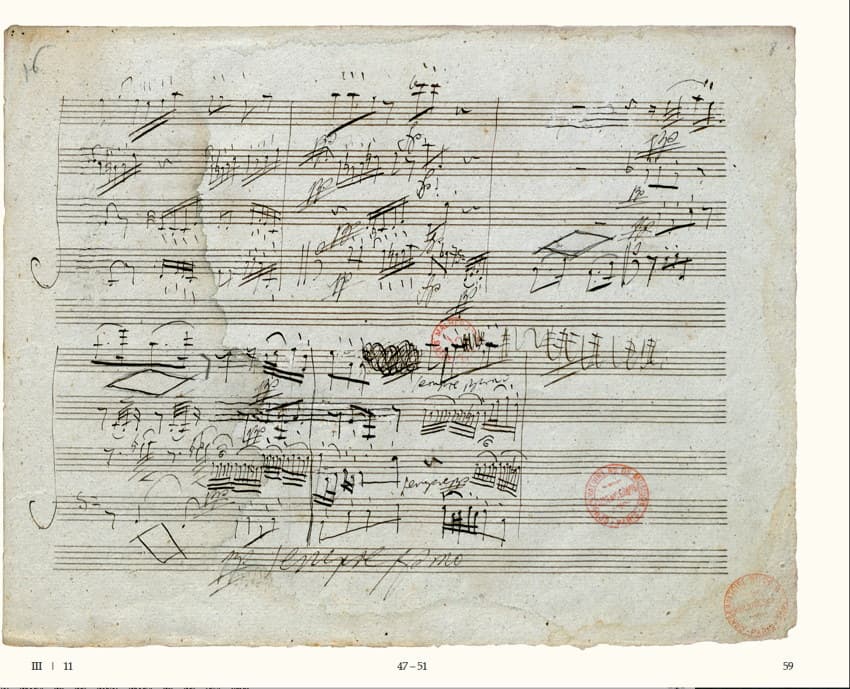

Ludwig van Beethoven: String Quartet in B-flat Major Op. 130, “Adagio-Allegro”

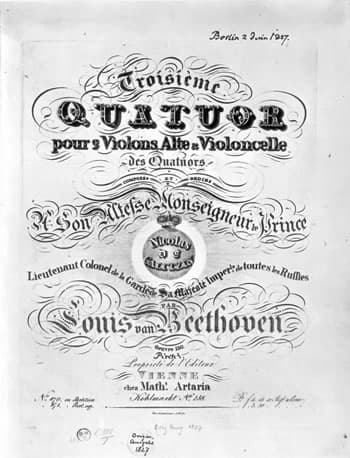

Music score cover of Beethoven’s String Quartet Op. 130

The review continues, “this reviewer does not dare to interpret the sense of the fugal finale; for him, it was incomprehensible, like Chinese. If the instruments in the regions of the south and north poles have to struggle with gigantic difficulties; if each of them is differently figured and they cross over each other per transitum irregularem amid countless dissonances; if the players, not trusting themselves, probably also do not play completely accurately, then the Babylonian confusion is certainly complete. Perhaps so much would not have been written down if the master were also able to hear his own creations. But we do not wish thereby to pronounce a negative judgment prematurely; perhaps the time is yet to come when that which at first glance appeared to us dismal and confused will be recognized as clear and pleasing in form.”

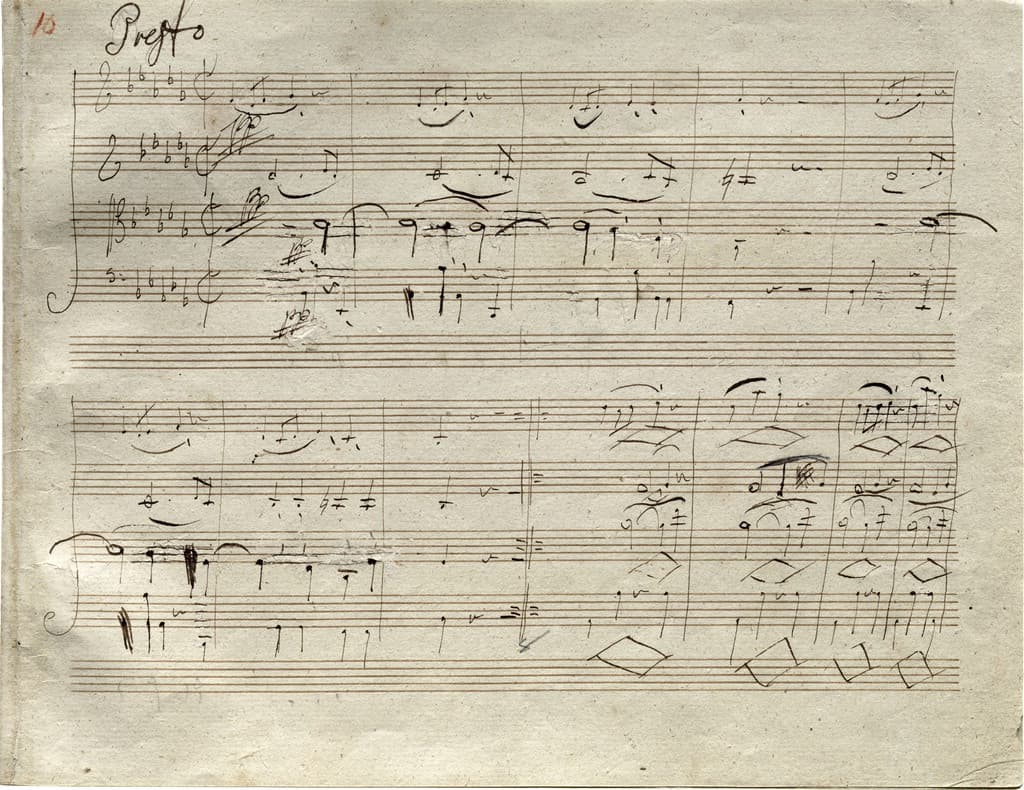

Ludwig van Beethoven: String Quartet in B-flat Major Op. 130, “Presto” (Bartok Quartet)

Beethoven’s String Quartet Op. 130 2nd movement

Much of the blame for the reviewer’s confusion was placed on the performance by the Schuppanzigh Quartet. In fact, Beethoven had engaged Schuppanzigh for violin lessons back in 1794. Beethoven reports that he went there three times a week, but we have no indication as to the duration or the nature of the student-teacher relationship. They did become fast friends, and when Count Razumovsky commissioned Schuppanzigh to assemble the finest string quartet in Europe in 1808, it provided Beethoven with a superb performance medium. It also allowed him to try out and fine-tune his compositions. A scholar writes, “Given the technical challenges of Beethoven’s late string quartets, the musical expertise of the Schuppanzigh quartet became invaluable.”

Ludwig van Beethoven: String Quartet in B-flat Major Op. 130, “Andante con moto, ma non troppo” (Petersen Quartet)

Beethoven’s Op. 130 4th movement

Beethoven worked on his Op. 130 intensively in the months from May to September 1825. It originates from a time that saw Beethoven dangerously ill, as he was suffering from an intestinal inflammatory disease. Adding to his medical condition, he was also involved in a stressful family situation involving his nephew Karl. A biographer writes, these months were full of personal confrontations, recriminations, mutual personal threats, and outright rebellions by both uncle and nephew.” It has been suggested that the high pitch of Beethoven’s personal emotions, and his morbid premonitions of death “were strangely balanced by the sheer positive success the composer was receiving after the premiere of the Ninth Symphony the previous year.” It is hardly surprising that this quartet covers the tremendous emotional ground that it does.

Ludwig van Beethoven: String Quartet in B-flat Major Op. 130, “Alla danza tedesca:Allegro assai” (Kodály Quartet)

Beethoven’s Op. 130 5th movement

The “Cavatina” is one of the most intimate movements ever composed, and it simultaneously expresses profound sadness and religious serenity. It begins and ends with a slow melody over which Beethoven writes “beklemmt.” This can be translated as oppressed, anguished, or stifled. With the lower voices pulsating in some distant tonality, the first violin “is somewhat overcome, no longer singing, no longer even able to connect one note to another. It is voiceless, yet desperate to give voice. The line cannot find tears with which to cry, it gropes for a language where there is none.” The movement becomes one of revelation, as “music is inadequate to express what pleads to be expressed, and that “failure is flawlessly expressed by music.”

Ludwig van Beethoven: String Quartet in B-flat Major Op. 130, “Cavatina: Adagio molto espressivo” (Alban Berg Quartet)

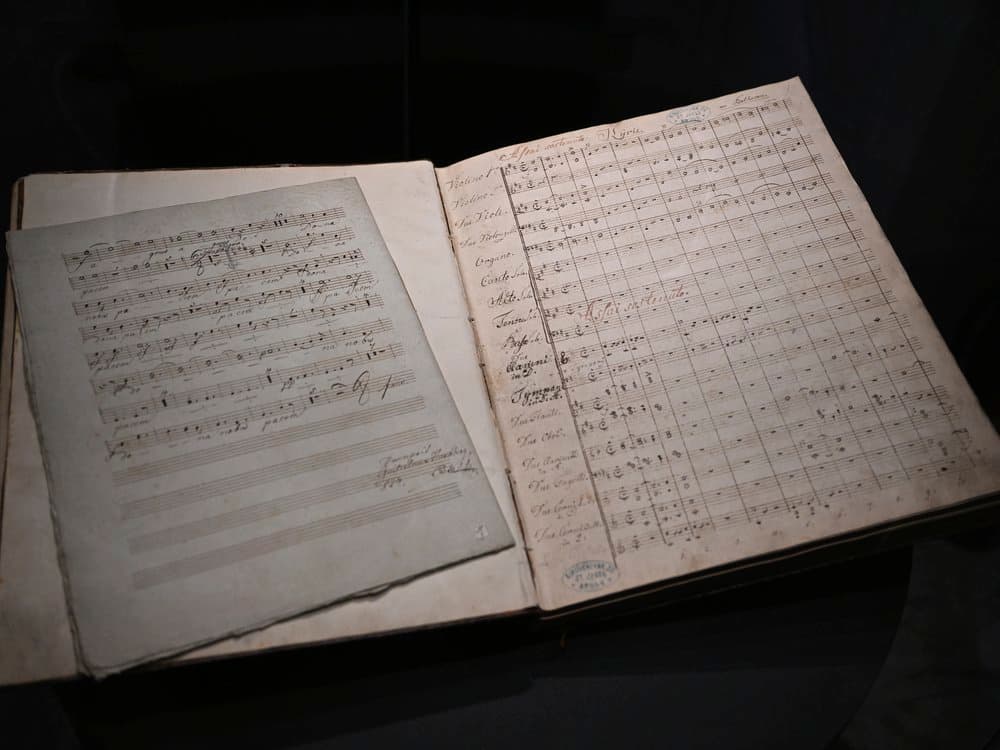

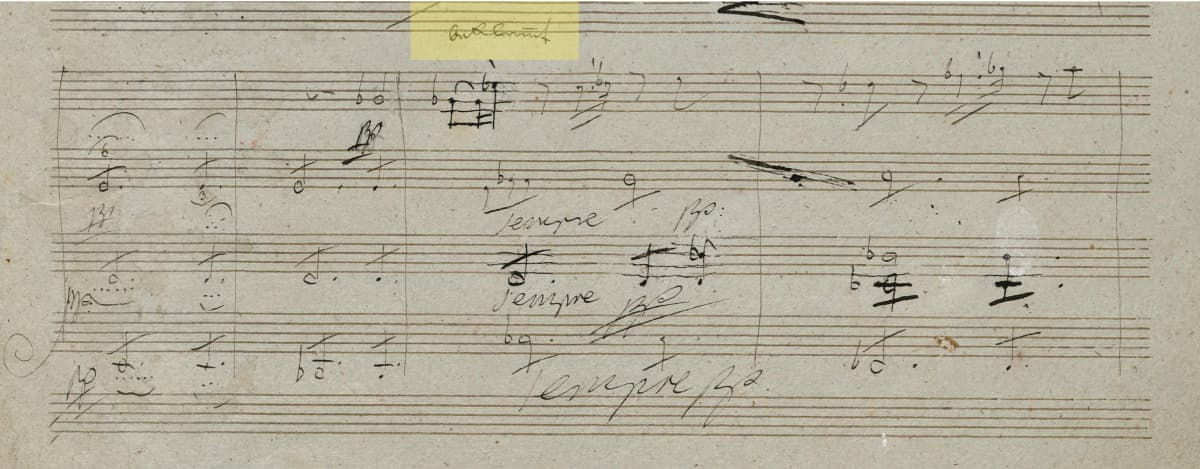

Beethoven’s Op. 130 “Große Fuge”

While the “Presto” and “Alla danza tedesca” were encored at the premiere performance, the “Große Fuge” completely mystified the audience. It quickly spawned rumors that Beethoven had indeed gone completely insane. His publisher Artaria became very concerned that he would be unable to sell the quartet with such an incomprehensible Finale. He enlisted Beethoven’s friends to try and convince him to make a substitution. Artaria also offered to pay Beethoven an additional fee to publish the Fugue separately and to provide a substitute Finale. After almost six months of negotiations, Beethoven surprisingly allowed the “Große Fuge” to be published as his Opus 133, and he went to work writing a lighter Finale. The “Grosse Fuge” contains elements of sonata form, fugue, variation, symphonic poem, and even a Baroque suite. Without satisfying the musical or structural demands of any of these categories, it represents “an extravagant essay toward both the reconciliation and the renunciation of all disparate musical styles contained in Op. 130.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Ludwig van Beethoven: String Quartet in B-flat Major Op. 130, “Große Fuge”