Maurice Ravel presented his one-act opera L’heure Espagnol, probably most idiomatically translated as “How They Keep Time in Spain,” at the Opéra-Comique on 19 May 1911. Based on the play by Franc-Nohain, which enjoyed great success at the Odéon in 1904, Ravel completed the score during a feverish spell of activity in 1907, but the path towards a first performance was an arduous one.

Maurice Ravel: L’heure Espagnol, “Air de Armiro”

The Play

Franc-Nohain

Ravel was first attracted to the play’s cool, ironic humour and vivacious language, and he wrote to Franc-Nohain requesting permission to adapt it. The author was amazed that anyone would consider setting his work to music and happily gave his permission.

Once the work had been completed, Ravel had to first worry about the failing health of his father Joseph Ravel. As he wrote despondently to Ida Godebska, “Things are not well at home. My father is weakening continually. His mental capacity is at its very lowest; he mixes up everything and no longer knows where he is at times.”

Maurice Ravel: L’heure Espagnol, “Introduction” (Orchestre National de France; Lorin Maazel, cond.)

Albert Carré

Albert Carré

The decision whether to mount a production of the work was in the hands of Albert Carré, the director of the Opéra-Comique. At first, he flatly refused to have anything to do with the opera, as the story about the amorous adventures of a clockmaker’s wife was considered too risqué for the stage.

Gradually, however, Carré warmed to the project but for one reason or another, the production was endlessly postponed. In the meantime, Durant published the piano-vocal score in 1908 and Ravel completed the orchestration one year later. Once again, L’heure Espagnol was scheduled to be performed with Feuersnot by Richard Strauss, but the production did not materialise.

Maurice Ravel: L’heure Espagnol, “Scene 4” (Orchestre National de France; Lorin Maazel, cond.)

Louise Cruppi

Louise Cruppi

It was time to look for support higher up, and Ravel enlisted the support of Louise Cruppi, the wife of Minister of Commerce and Industry Jean Cruppi. As Ravel wrote to Ida Godebska, “Cruppi was shocked by Carré’s refusal, and her first impulse was to write to him directly. After mature consideration, she decided nevertheless to follow her impulse, and the most pungent exchange of correspondence followed.”

Finally, fragments of the opera were heard in a concerto performance in 1910 and Mme Cruppi herself sang the character of Conception. The performance was a marked success, and a critic posed the question which had disturbed Ravel for three years,“When will L’heure Espagnol finally be performed at the Opéra-Comique?”

Maurice Ravel: L’heure Espagnol, “Scene 7” (Orchestre National de France; Lorin Maazel, cond.)

Risqué Subject Matter

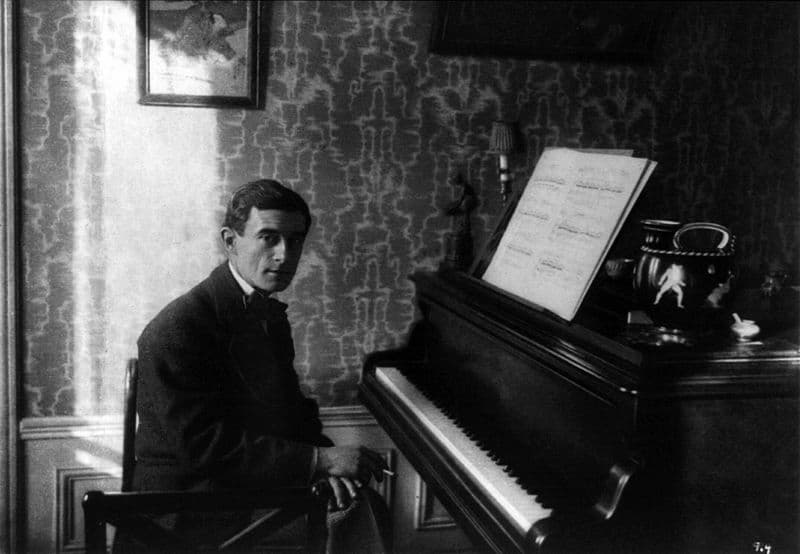

Maurice Ravel at the piano, 1912

Carré’s objections to the opera included not merely its risqué subject matter but also its text-setting, which follows the natural rhythms and inflections of spoken French to the exclusion of more conventional lyricism. Yet, the pressure put on by Mme Cruppi, to whom Ravel would dedicate the work, finally paid off, and a read-through of the opera was held in the foyer of the Salle Favart on 20 February 1911.

By 25 April, the production had moved into the theatre, and orchestral rehearsals began on 28 April. Three days later, the singers and the orchestra rehearsed together for the first time. The production went through some casting changes, and Ravel wrote a long letter to the editor of Le Figaro, attempting to reassure both the public and critics. The letter was excerpted in the newspaper two days before the premiere.

Maurice Ravel: L’heure Espagnol, “Scene 12” (Orchestre National de France; Lorin Maazel, cond.)

Public Reassurance

Ravel’s L’heure Espagnol

Ravel writes, “What have I attempted to do in writing L’heure Espagnol? It is rather ambitious to regenerate the Italian opera buffa—the principle only. This work is not conceived of in traditional form…Apart from a few cuts, I have not altered anything in Franc-Nohain’s text… I was thinking of a humorous musical work for some time and decided that this droll fantasy was just what I was looking for.”

Ravel continues, “many things in this work attracted me, the mixture of familiar conversation and intentionally absurd lyricism, and the atmosphere of unusual and amusing noises which surround the characters in this clockmaker’s shop. Finally, the opportunities for making use of the picturesque rhythms of Spanish music.”

Maurice Ravel: L’heure Espagnol, “Scene 21” (Orchestre National de France; Lorin Maazel, cond.)

Transcendental Jujitsu

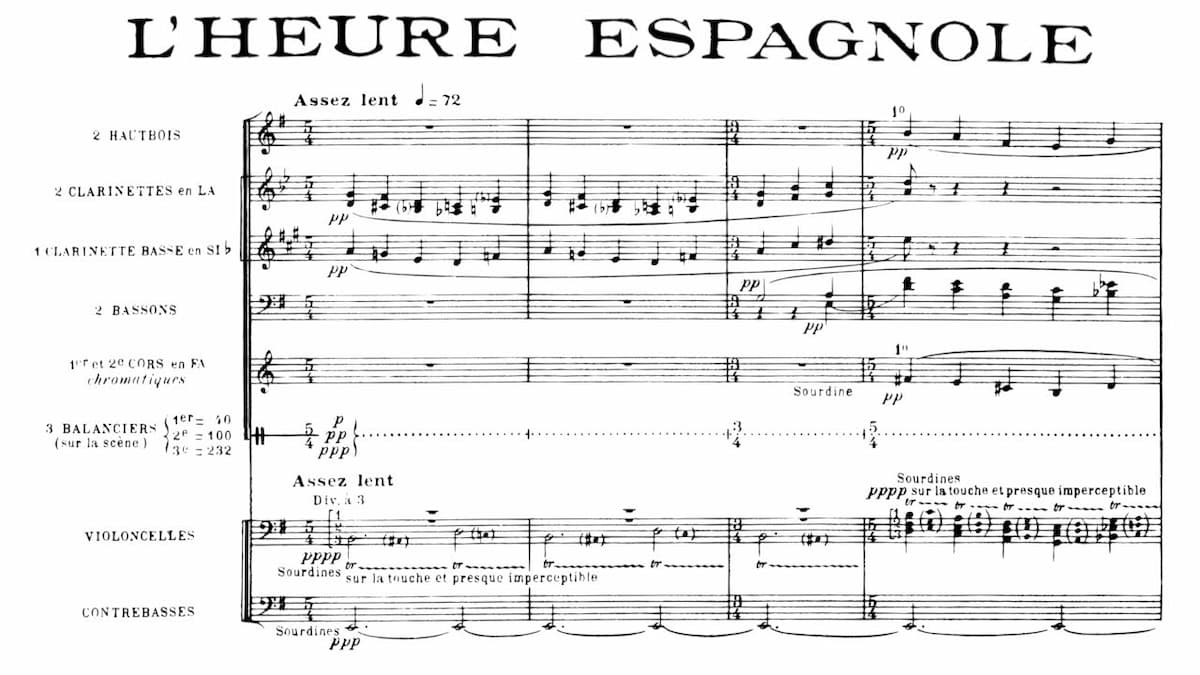

Ravel’s L’heure Espagnol music score

Ravel’s opera was presented in a double bill after Massenet’s Thérèse, and reactions were decidedly mixed. Pierre Lalo found that “Ravel’s air of detached superiority spoilt his enjoyment,” while Reynaldo Hahn, referring to Ravel’s technique as a “sort of transcendent jujitsu,” preferred those diatonic moments in the score which the composer had failed to hide beneath the Hispanic chromaticism.

The libretto was called “mildly pornographic vaudeville,” and a critic writes “Ravel knows the unknowable, moulds the imponderable, and juggles with atoms and ions. He creates colours and perfumes. He is a painter, goldsmith, and jeweller… In the name of logic, Ravel removes from the musical language not only its internationalism and its universality but its simple humanity.” L’heure Espagnol ran for an initial nine performances, but it was not revived.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter