Charles Gounod (1818-1893) wrote 12 operas, with Faust as his most popular. Premiered at the Théâtre Lyrique on the Boulevard du Temple in Paris, on 19 March 1859, the work was an immediate success. While the original version employed spoken dialogue, the opera reached its final form as a grand opera produced for the Paris Opéra in 1869. In this final version the spoken dialogue was transformed into recitative and a ballet scene was added as well.

Charles Gounod: “Ah, je ris de me voir si belle” Faust, Act III

Dramatized Faust

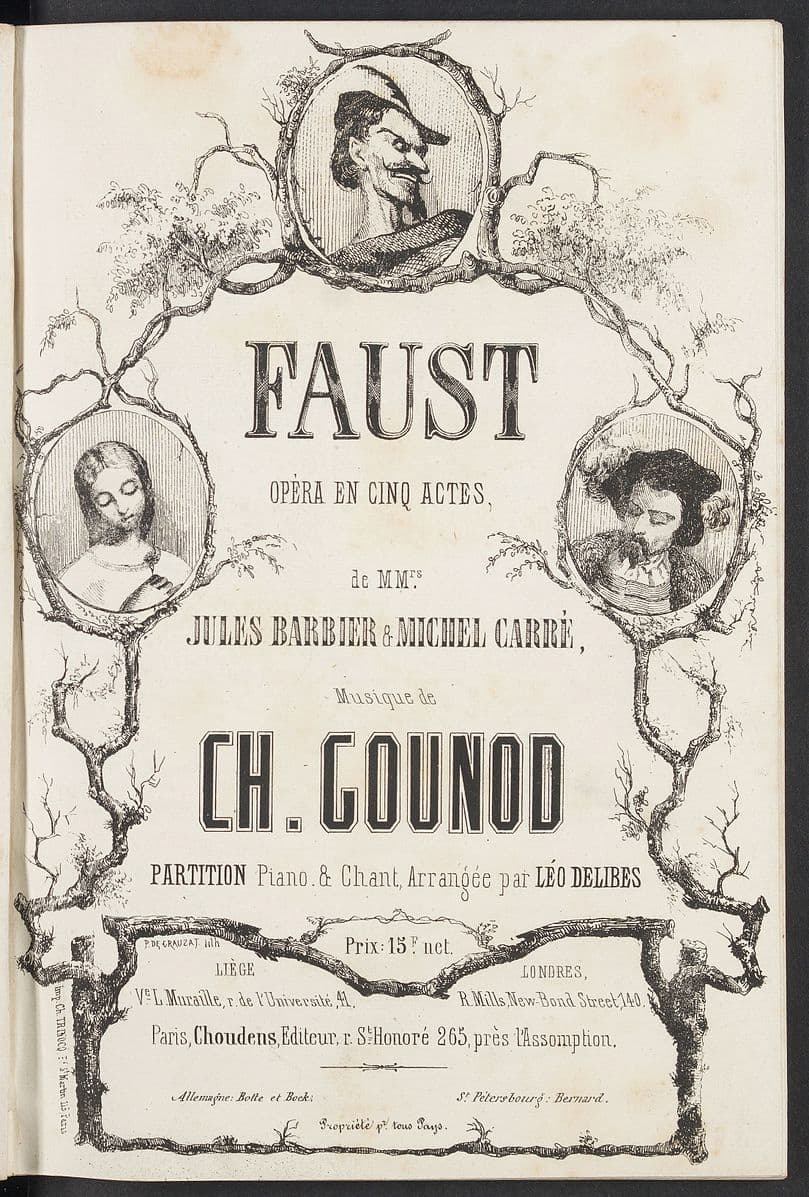

Gounod first read Goethe’s Faust in 1838, but interest in this subject as an opera was aroused by a performance at the Théâtre du Gymnase-Dramatique in 1850. This particular stage version of the Faust legend by Michel Carré became the basis for the libretto supplied by Jules Barbier. The play and libretto are loosely based on Part One of Goethe’s Faust.

Charles Gounod

The theatrical play and opera libretto hinge on three basic themes. Initially, it deals with the love affair between Faust and Marguerite. Faust, following the deceptive practices of Méphistophélès, is ambiguous in his declaration of love. Marguerite, on the other hand, being naïve and devout, completely believes his declaration. Eventually Faust loses faith in Méphistophélès and recognises the error of his ways.

Charles Gounod: Faust (1864 version) (Carlo Colombara, bass; Aljaž Farasin, tenor; Diana Haller, mezzo-soprano; Marjukka Tepponen, soprano; Rijeka Opera Choir; Rijeka Opera Symphony Orchestra; Ville Matvejeff, cond.)

Basic Themes

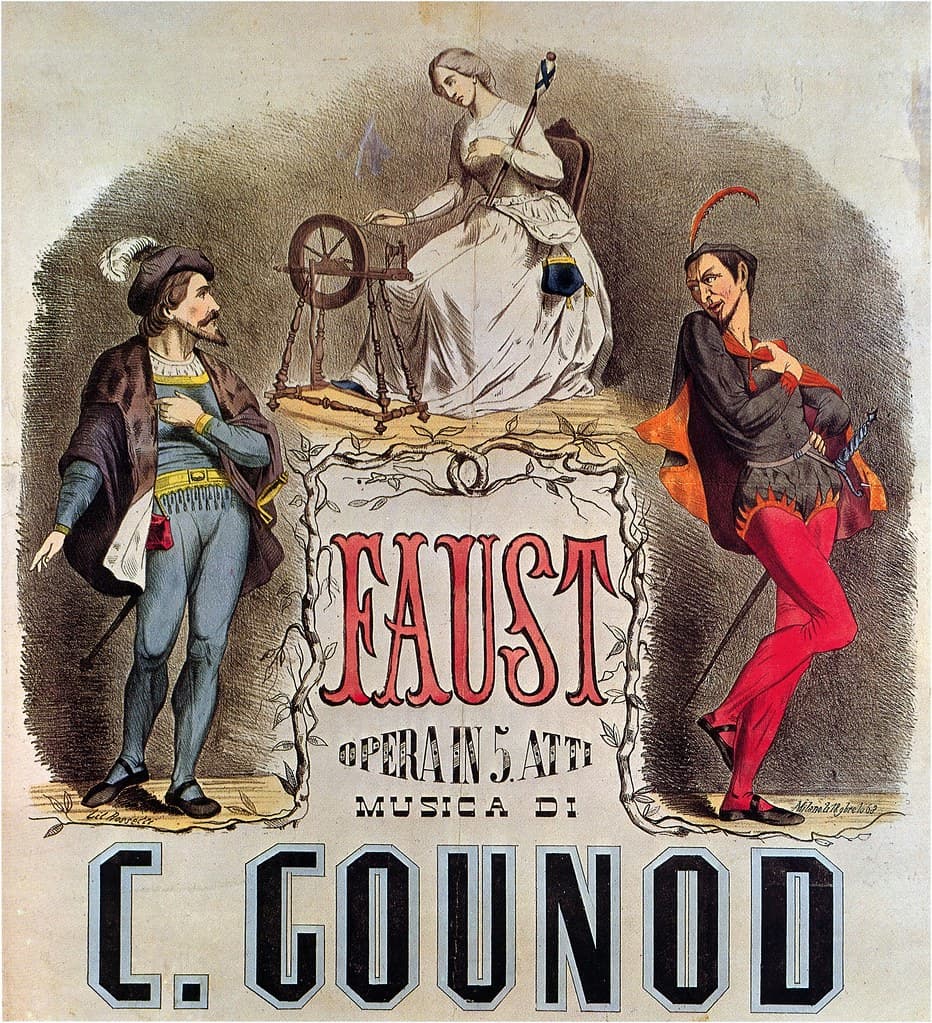

Gounod’s Faust poster, 1863

Morality becomes the second important theme of the libretto, and Marguerite symbolises a severe warning on sin. She surrenders to Faust and bears him a child. However, to cover up her crime against morality, she murders the child. Her repentance enables her to unveil the dark powers and influence of Méphistophélès, and she is rewarded with salvation akin to the assumption of the Virgin Mary.

The final theme of the libretto addresses the fantastic and supernatural. A scholar writes, “since the first performance of Meyerbeer’s opera Robert le diable in 1831, Parisian audiences had been bewitched by works which referenced the supernatural, and Faust benefited greatly in terms of popularity from this fascination.” To be sure, the story of Faust offered countless opportunities for spectacular stage effects that attracted 19th-century audience.

Charles Gounod: “Avant de quitter ces lieux,” Faust, Act II

The Plot

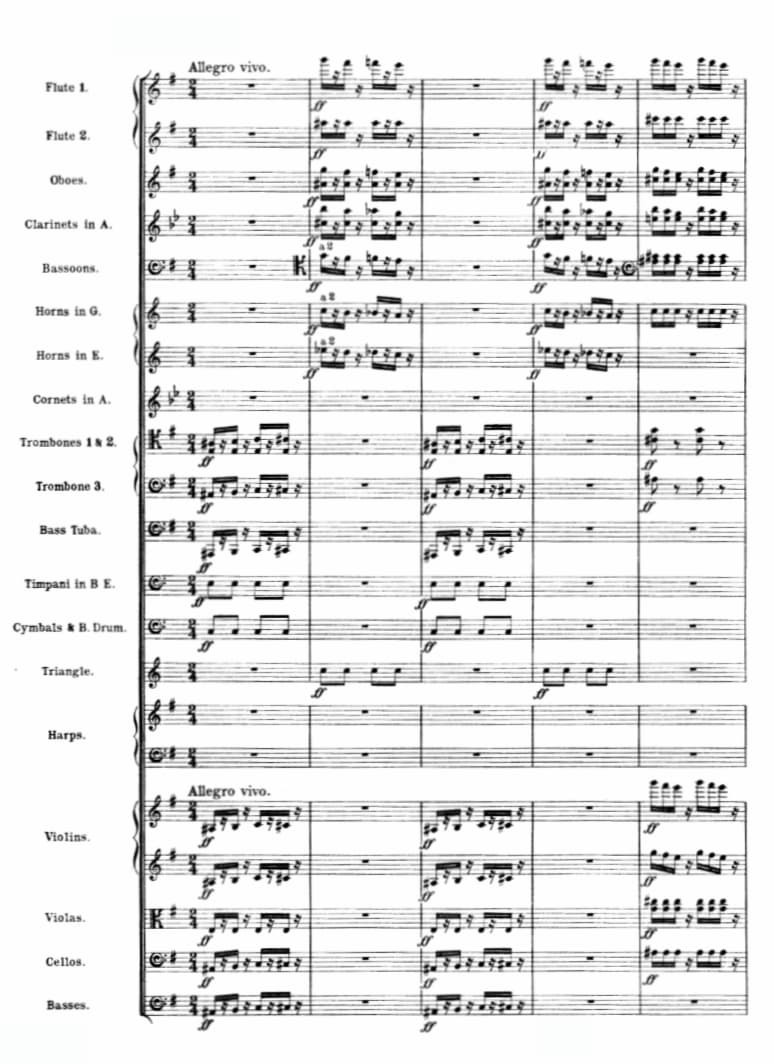

Faust’s ballet score – finale

Unfolding over five acts, we initially learn that Faust, a man of science, is disillusioned with life and resolved to commit suicide. As he curses God, Méphistophélès obligingly appears and offers Faust riches, power, or glory. Faust, however, only wants to recapture the innocence of youth. They agree on a bargain for Faust’s immortal soul, and Méphistophélès conjures up a vision of Marguerite to expedite proceedings.

We are introduced to Valentin, a soldier and Marguerite’s brother, and his friend Wagner in Act II. They interact with Méphistophélès, who tells fortunes. Wagner is to be killed in battle, and Valentin will also meet his death. Valentin is angered and both draw their swords. Valentin’s blade shatters, and Méphistophélès leads Faust to Marguerite. He offers her his arm, but she refused. Nevertheless, Faust is ever more entranced.

Charles Gounod: ”Salut! demeure chaste et pure” Faust, Act III

Seduction and Reckoning

Siébel, a youth in love with Marguerite and picking flowers, is watched by Méphistophélès and Faust. Instead of flowers, Méphistophélès leaves a box of jewels for Marguerite, which she finds and puts on. When she looks in the mirror, she sees a different woman and is further confused by the encouragement of her neighbour Marthe. Faust and Méphistophélès return, and while Méphistophélès flirts with Marthe, Faust seduces Marguerite.

Charles Gounod: Faust

Seduced and abandoned, Marguerite is expecting Faust’s child. She is still in love with him and prays for him and their unborn child. Valentin returns and is fatally wounded in a tussle with Méphistophélès. Watching her brother die, she goes to church to pray for forgiveness. When she hears the voice of Méphistophélès telling her that she is damned, she collapses in terror.

Charles Gounod: Faust (1864 version) – Act III Scene 6: Chanson du Roi de Thulé: Il était un roi de Thulé (Marjukka Tepponen, soprano; Rijeka Opera Symphony Orchestra; Ville Matvejeff, cond.)

The Final Act

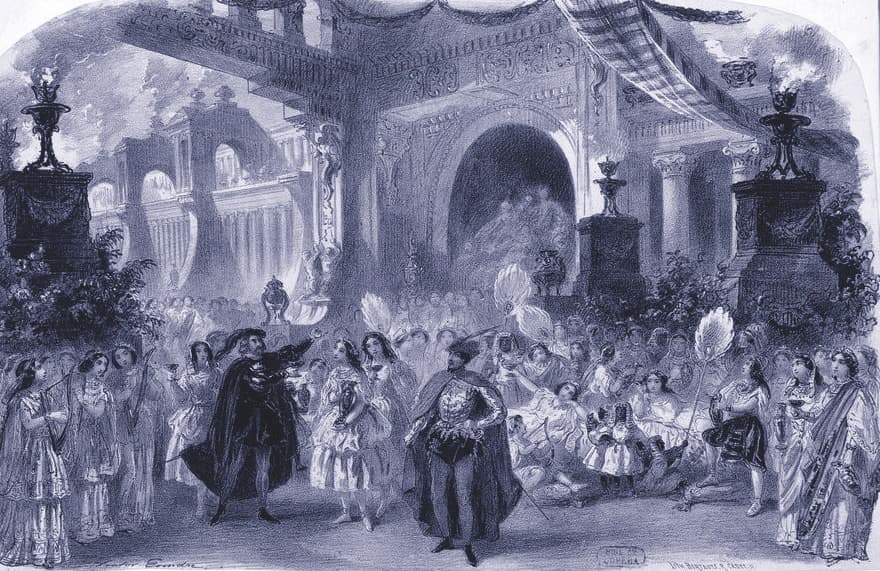

Scene from original production of Faust by Charles Gounod

On Walpurgis Night, Faust and Méphistophélès are in the company of demons, and he shows him a vision of Marguerite, who has been imprisoned for infanticide and gone insane. Faust goes to the prison in an attempt to save her, and she recognizes her lover and remembers the night when she was first seduced. Faust is overwhelmed with pity, and panicked by the sight of the devil, Marguerite makes a frantic appeal to the heavens and dies. Méphistophélès damns her, but angelic voices proclaim she is saved.

The opera became an important part of the French musical establishment, as it was composed by a winner of the Prix de Rome. To contemporary audiences the greatness of Faust was found in the qualities of naturalness, simplicity, sincerity and directness of emotional appeal. As a critic wrote, “Gounod’s great desire was to discover a beautiful colour of orchestral palette,” and its initial assessment as “Wagnerian” became an important feature of French musical aesthetic.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter