Samuel Barber had always been looking for success in the opera house, an achievement that sadly eluded him. The story was markedly different in the field of instrumental music, as his Overture The School for Scandal was performed by the Philadelphia Orchestra soon after graduating from the Curtis Institute of Music.

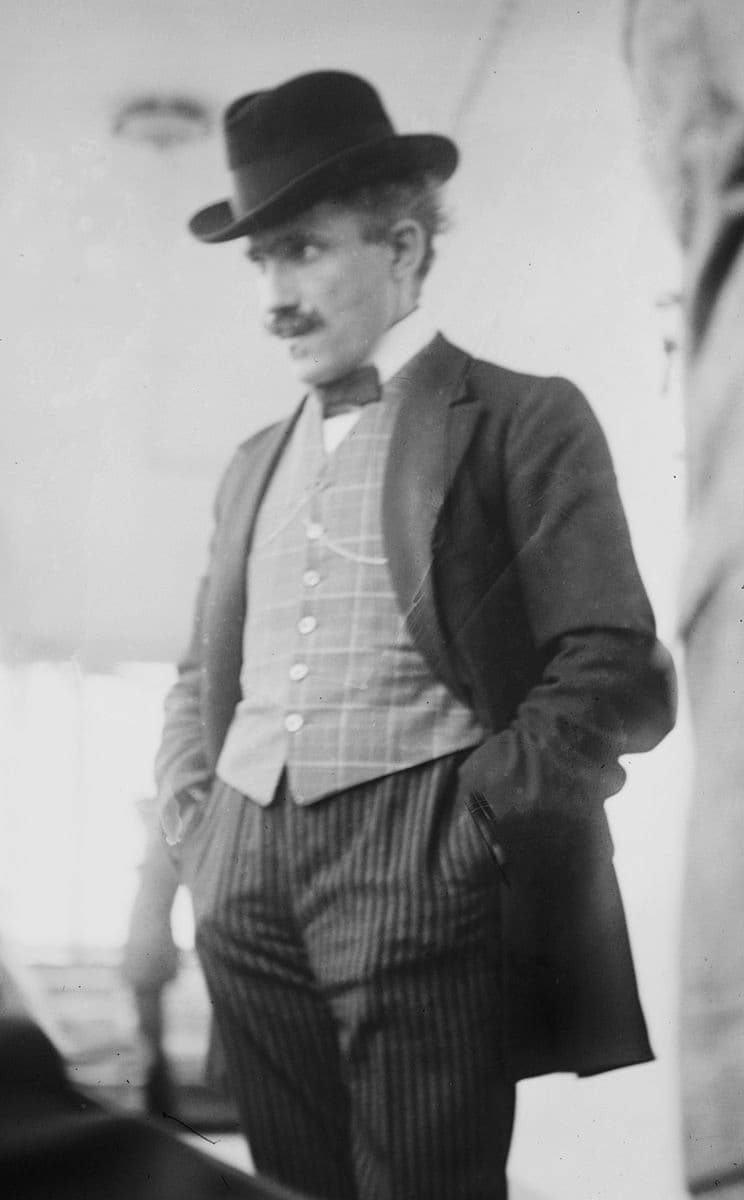

Arturo Toscanini

Arturo Toscanini gave the premiere performance of the Adagio for String a few years later, and shortly before his death, his Third Essay for Orchestra premiered on 14 September 1978 in Avery Fisher Hall. On that occasion, Zubin Mehta conducted the New York Philharmonic in his debut as music director.

Barber really never explained what the title “Essay” actually meant. When he was asked to explain his choice of the word, he simply referred to the Oxford English Dictionary definition. “A composition of moderate length on a particular subject… more or less elaborate in style though limited in range.”

Samuel Barber: Third Essay for Orchestra, Op. 47 (Detroit Symphony Orchestra; Neeme Järvi, cond.)

Backstory

Samuel Barber

Barber’s Third Essay for Orchestra had a somewhat complicated prehistory. In 1976, Eugene Ormandy, the Philadelphia Orchestra’s music director, was approached by an anonymous patron offering a $75,000 commission from the Merlin Foundation. The commission asked for a large-scale work to be premiered by the Philadelphia Orchestra.

That anonymous patron was later identified as Audrey Sheldon Poon, an American socialite. She was the daughter of Huntington D. Sheldon and Magda Merck, the youngest daughter of George Merck, founder of the pharmaceutical firm Merck & Co. The contract came to be signed, but a series of disagreements soon followed. Apparently, the Philadelphia Orchestra Association could not accept some of the conditions.

In the end, the arrangement was terminated, but we are still uncertain whether it was Barber or his patroness who pulled the plug. In the event, the cheque was returned to the Merlin Foundation. Mrs. Poon, at this point divorced from her husband and using her maiden name Audrey Sheldon, would not let go of the commission for an orchestral work and approached the New York Philharmonic. When all was set and done, Barber received a check for $60,000.

Samuel Barber: Second Essay for Orchestra, Op. 17 (Symphony of the Air; Vladimir Golschmann, cond.)

Earlier Essays

Samuel Barber’s First Esssay

The fiery Italian maestro Arturo Toscanini was not particularly keen on modern music, especially not American music. However, the live radio broadcast on 5 November 1938 was going to be special. Toscanini had finally found a living American composer he could champion. That composer was Samuel Barber and the piece was his Essay for Orchestra.

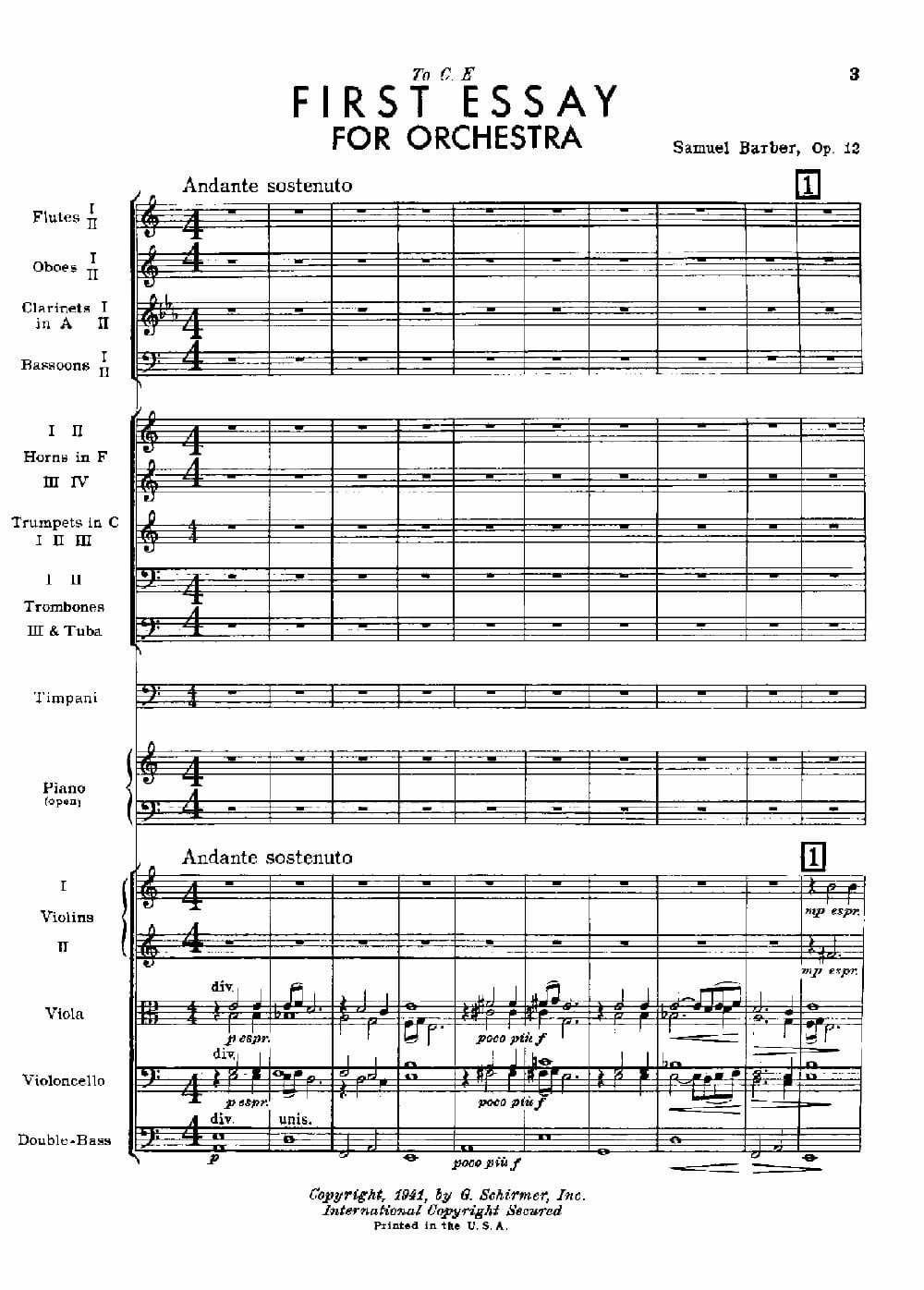

That First Essay is scored in two parts and opens with a melancholic melody in the violas. As the orchestra takes up this tune it becomes more agitated and developed with the trumpets reaching for the climax. This section ends with the opening melody sounding in the strings. A more upbeat second part presents a development of the opening melody before it comes back in its entirety. The trumpet fanfare returns and the work gradually fades away.

Samuel Barber: First Essay for Orchestra, Op. 12 (RAI Symphony Orchestra, Rome; Daniel Kawka, cond.)

Second Essay

Samuel Barber’s Second Essay

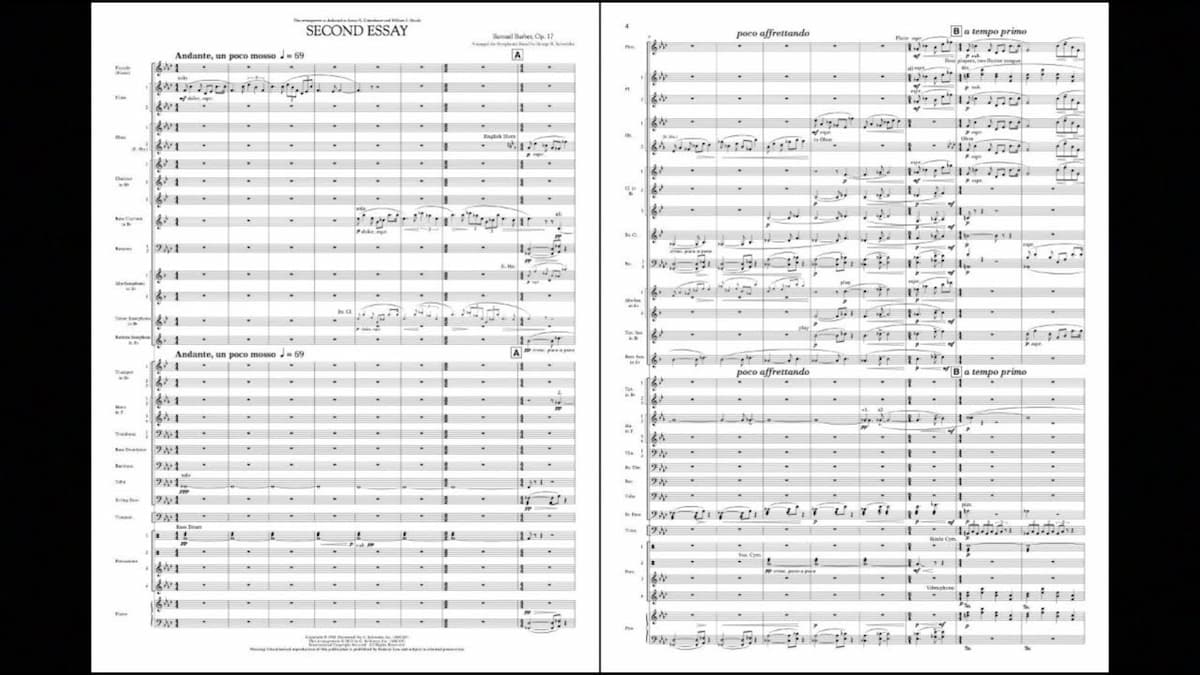

In his Essay for Orchestra Op. 12, Barber explored a new single-movement format for a concert piece. On commission from Bruno Walter, Barber crafted his Second Essay for Orchestra. Composed alongside his Violin Concerto, the work presents a self-contained, abstract music structure not tied to a particular programme. The only influence extrinsic to the music that may be discernible, remarked Barber, is the fact that the piece “was written in wartime.”

Bruno Walter

Towards the end of his life, Barber composed his Third Essay for Orchestra, a form Barber had invented several decades earlier. According to the composer, this essay is absolutely abstract and more essentially dramatic, and it is less lyric in character than the first two essays, although the central section includes several lyric themes.

As a commentator wrote, “the piece has a large orchestral sweep but is cast in a single, unbroken, tightly wrought movement, all of the material is generated from the opening percussion figure.” Barber’s Essays are occasionally scheduled for performance, but the immense popularity of the Adagio for Strings tends to eclipse everything Barber subsequently composed.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter