It was May 7, 1824, and Vienna’s Kärntnertor Theater was about to witness history—or possibly a musical trainwreck. Beethoven, profoundly deaf, took the stage for the premiere of his Symphony No. 9 in D minor. The night would turn out to be historic, but it was a seriously messy and chaotic affair.

The creation of that symphony is a tale of grit, genius, and a touch of glorious madness. Beethoven was in his early 50s, and he battled severe health issues, including chronic abdominal pain, jaundice, and near-total deafness.

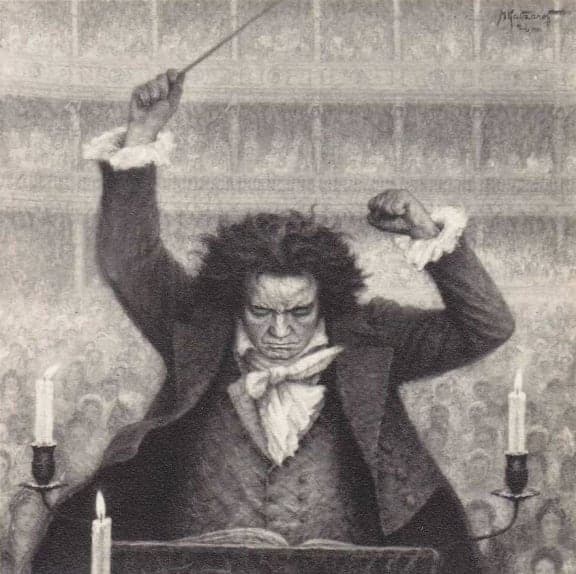

Chaotic Circumstances

Beethoven conducting

His personal life was in shambles as he moved restlessly from one messy apartment to the next, and his friendships were seriously strained. He was also engaged in a bitter custody battle over his nephew Karl.

Yet, amidst this chaos, Beethoven embarked on one of the most ambitious projects of his career, composing a symphony that would redefine the genre and leave an indelible mark on music history.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125 “Allegro ma non troppo”

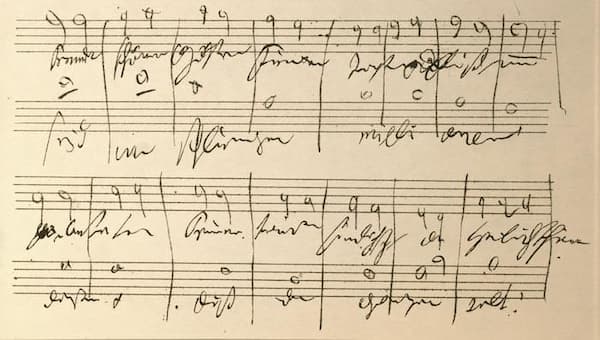

Composition History

Beethoven’s Ode to Joy

Beethoven worked on his 9th for roughly 2 years, sketching obsessively in tiny notebooks that are now treasured for their chaotic brilliance. Deafness forced him to imagine sounds he could no longer hear.

He envisioned a four-movement structure: a stormy first movement, a lively scherzo, a serene adagio, and a finale that would erupt into a choral celebration of joy. The famous “Ode to Joy” theme, a deceptively simple melody, was refined over years until it became the anthem we know today.

The Rehearsals

The rehearsal process was a comedy of errors as the chorus tasked with singing Schiller’s “Ode to Joy” was woefully underprepared. The soloists grumbled about the vocal parts being absurdly high, while the orchestra struggled with the symphony’s fiendish complexity.

Beethoven was still making corrections to the score and copyists were churning out parts riddled with errors. And to top it all off, the theatre had been double-booked. I would have loved to hear the conversation between the stage manager and Beethoven, telling him that his symphony would have to make way for a ballet troupe.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125 “Molto vivace”

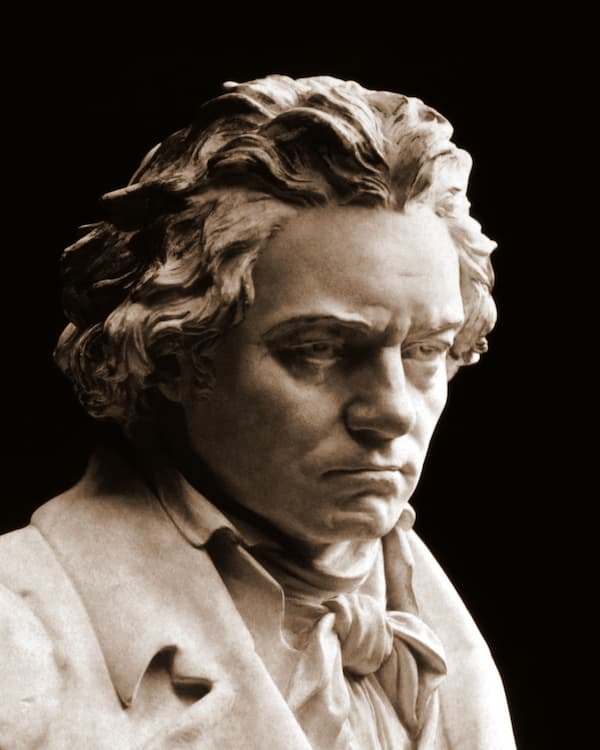

Beethoven’s Feelings

Photograph of bust statue of Ludwig van Beethoven by Hugo Hagen

On the night of the premiere, Beethoven likely experienced a mix of anxious anticipation, pride, and frustration. He insisted on conducting despite his deafness, relying on visual cues only.

Luckily, the concertmaster, Michael Umlauf, had told the orchestra to ignore Beethoven’s erratic conducting and to follow his instructions. Beethoven was just lost in his own sonic universe, beating time to a rhythm only he could hear.

The audience was a mix of Viennese aristocrats, music enthusiasts, and curious onlookers. They didn’t know whether to be awestruck or bewildered. The piece was over an hour long, with a finale that threw in a choir, soloists, and a Turkish march.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125 “Adagio molto e cantabile”

Reactions

One critic later called it “a work of incomprehensible grandeur,” a polite way of saying “what was that?” Yet, despite the chaos, Beethoven’s rogue conducting, the singers’ panic, the orchestra’s struggles, the premiere was a triumph.

By the end of the performance, Beethoven was still conducting, oblivious that the music had stopped. Finally, the contralto soloist Caroline Unger gently tugged him around to face the roaring crowd. The audience, packed to the rafters, erupted in applause, tossing hats and handkerchiefs, while Beethoven squinting in confusion.

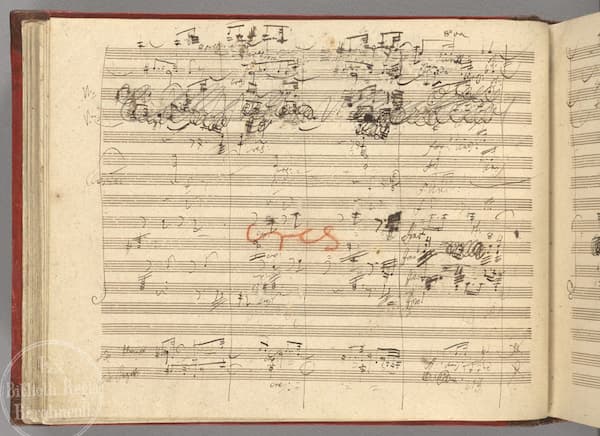

Mixed Feelings

Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 Autograph score

Beethoven’s friend Anton Schindler noted the composer’s exhaustion but also his elation at the symphony’s impact. Given his perfectionism and the premiere’s technical flaws, he may have felt some dissatisfaction, but the audience’s reception likely affirmed his sense of triumph.

The Ninth was on its way to immortality, proving that the best art sometimes comes from a gloriously unhinged mess. Given Beethoven’s ill health and isolation, this triumph must have been tempered with a sense of melancholy. After all, he and his audience were probably already aware that this might have been his final major work.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter