Credit: http://si.wsj.net/

A nocturne is a work of the night – its meaning comes from words such as ‘nocturnal’ – and in Mozart’s time, meant works to be performed late at night, such as his Notturno, K. 286. By the 19th century, however, “nocturne” had changed meaning and was now a piano work, generally featuring a song-like melody in the right hand over a apreggiated accompaniment in the left hand, as if imitating a strummed guitar. Field’s nocturnes were important in creating new fields for piano writing. Liszt wrote that they ‘opened the way for all the productions which have since appeared under the various titles of Songs without Words, Impromptus, Ballades, etc., and to him we may trace the origin of pieces designed to portray subjective and profound emotion’.

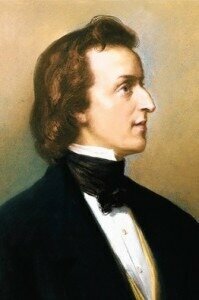

Chopin took up the new genre and changed everything: his works were more emotionally intense, were more inventive melodically, and were more complex, both in harmony and in counterpoint.

Today we’re looking at the complete nocturnes of Chopin as recorded in 2009 by Pascal Amoyel. It won the Fryderyk Chopin “Grand Prix du Disque” in Warsaw in 2010 and as you listen to it, you understand why these are pieces of the night. The opening work, the Berceuse, op. 57, is a wonderful piece for setting up the entire recording because a berceuse is a lullaby, a work for lulling children to sleep, and it immediately plunges us into the night and into the mood for nocturnes.

Chopin: Berceuse, Op. 57

From his very first published nocturne, No. 1 in B flat minor, Op 9/1, of 1830, Chopin has taken the genre for his own.

Chopin: Nocturne No. 1 in B flat minor, Op. 9, No. 1

Pascal Amoyel

Credit: http://www.carteblanchemusique.com/

Chopin: Nocturne No. 9 in B major, Op. 32, No. 1

By the time we get to his final nocturnes, written in 1846, we have moved from works from the deepest night to works of twilight. The sound of his Op. 62, No. 1, Nocturne No. 17, is brighter and less introspective. The left hand is less active than in earlier nocturnes, and the melodic writing is filled with silence as an adjunct to the sound – sometimes it’s what isn’t said that reveals as much as what is said.

Chopin: Nocturne No. 17 in B major, Op. 62, No. 1

As Liszt wrote, the Nocturne opened up the world for new character pieces for the piano, freeing piano writing to become more introspective. The Amoyel recording is beautiful in its realization and goes a long way to helping us understand what an important work the nocturne was in its day. These are works for a small room, not a concert hall, so sit back comfortably, turn down the lights, and listen to a few nocturnes to help slow down your day and give it some thoughtful meaning.

Discography