In 2015, a 15th-century parchment book of songs was discovered and in the book were 12 previously unknown songs. All were given without attribution but modern scholars examining them have discovered links with works of many of the greatest composers of the era.

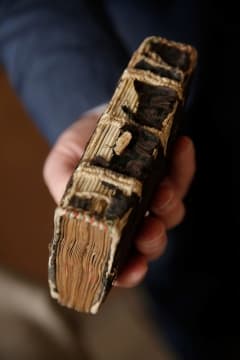

The Leuven Chansonnier, as it is now known, was copied in France, in the Loire Valley around 1470. When found, the chansonnier was in its original binding and, most unusually, still had its original index, giving an indication of the total contents of the book – no works were missing.

The Leuven Chansonnier, Photo by Rob Stevens

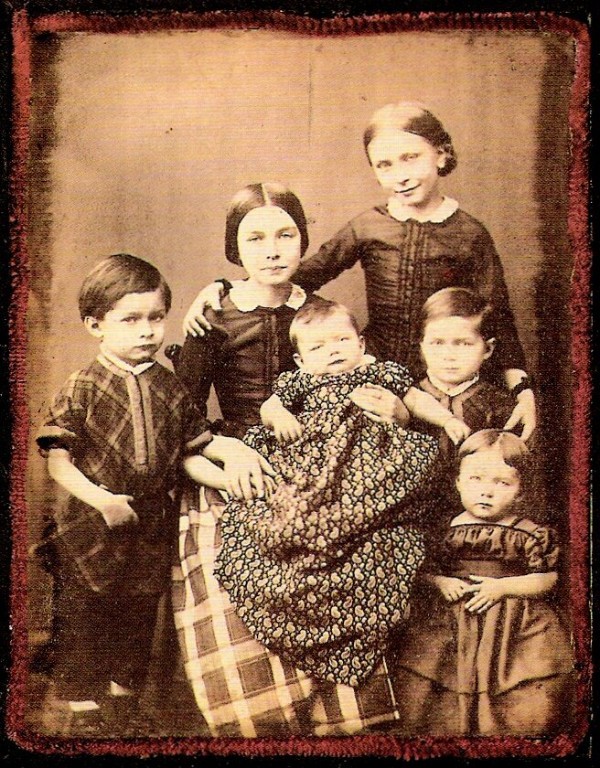

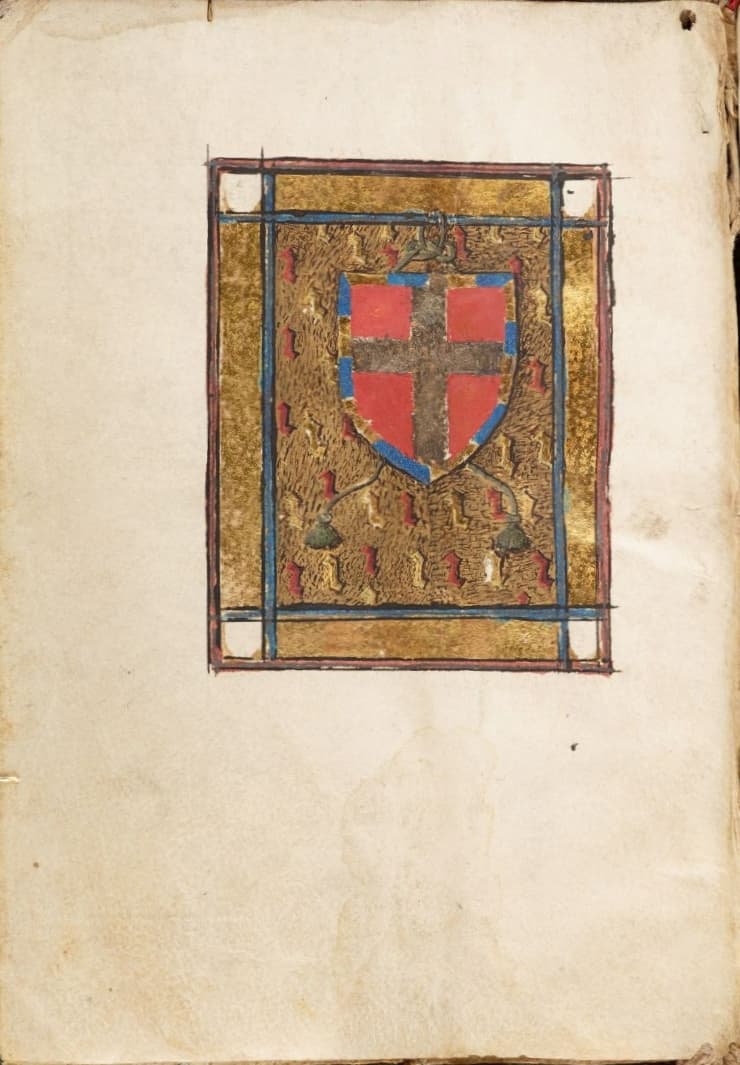

What isn’t known is the background of the book: Why was it created? Who was its owner? Who commissioned the work? An early page bears the coat of arms of the Dukes of Savoye-Nemours, but it is not thought that it indicates the first owner, but rather a later one, i.e., Jacque de Savoye (1531–1585) taking advantage of a blank page at the front of the book.

The Savoye-Nemours coat of arms

The book contains 50 pieces, all but one for 3 voices. Of the six chansonniers originating in the Loire Valley, in central France, the Leuven book is the smallest in size. In comparison with other 15th century chansonniers, the one it is most alike is the Chansonnier Cordiforme, which was copied about the same time, but in Savoy, south eastern France. The books have comparable numbers of pieces: Leuven: 50, Cordiforme: 43. They have many songs in common, and the number of famous songs of the period is higher than for comparable manuscripts. Lastly, neither the Leuven nor the Cordiforme gives composer attributes to the pieces in collections, unusual for the time.

A quarter of the Leuven songs are ‘unica’, i.e., unique to this particular manuscript. This is not really unusual, but, in music studies, unica are usually set aside, interest being more in the works that repeat from manuscript to manuscript, showing what was popular at the time. However, the Leuven unica, by virtue of appearing more than 550 years after their writing, in rather an ironic way, are ‘among the most studied anonymous pieces of the early Renaissance’.

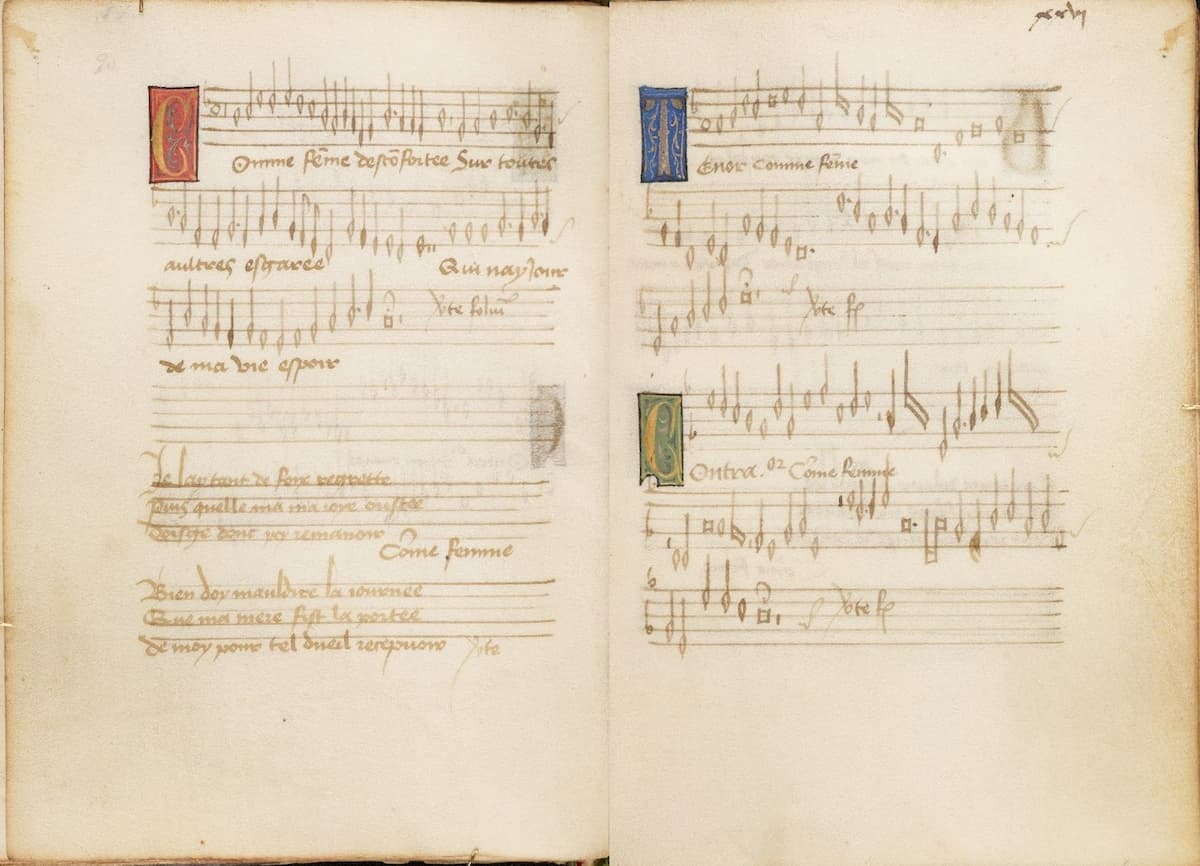

Several of the unica refer to existing songs, either through quotations of the other song’s music or text or through copying an unusual feature of the other song. Some of the known songs in Leuven also have unusual characteristics: Binchois’ Comme femme desconfortée has a new contratenor part and Caron’s Cent mil escuz has a long text verse not seen before.

The Leuven Chansonnier: Binchois: Comme femme desconfortée, part 1, col. 24v, 25r, with the new contratenor part

Gilles de Bins dit Binchois: Comme femme desconfortée (Els Janssens-Vanmunster, Grace Newcombe, discantus; Jacob Lawrence, Marc Lewon, Marc Mauillon, tenor; Raitis Grigalis, contratenor; Marc Lewon, cond.)

The unica presents some interesting music. In Hélas mon cueur, the top two voices are written in the same range and intertwine and tumble over each other at the same pitch level. In the text, the poet addresses his heart, which he accuses of trying to kill him by not loving the ladies that are around him. His unresponsive heart will make the poet languish and die.

Anonymous: Hélas mon cueur, tu m’occiras (arr. for 2 voices and lute) (Els Janssens-Vanmunster, Tessa Roos, discantus; Marc Lewon, lute and cond.)

One of the most beautiful of the unica is En atendant vostre venue, where the courtly lover awaits the return of her beloved. “While awaiting your return, my dear one whom I so desire, one hour seems to last forever when I lose sight of you alone”.

Anonymous: En atendant vostre venue (arr. for voice, vielle and viola d’arco) (Grace Newcombe, discantus; Baptiste Romain, Renaissance violin; Elizabeth Rumsey, viola d’arco; Marc Lewon, cond.)

The musical form of nearly all of the unica is that of the virelai. The virelai (along with the ballade and the rondeau) was the dominant musical form in France in the 14th and 15th centuries. The musical structure is ABBA, and probably came from 11th-century song forms originating in Arab songs from north Africa and Spain. These influenced the music of the Provençal troubadours and the music of the Spanish court. At first for just a single voice, by the 14th century, the virelai was used for polyphonic music. Most virelai texts are on courtly love but others may take their love metaphors from hunting, battle, or bird scenarios, with imitation of those activities in the musical setting. Eventually, the virelai was replaced by the other two formes fixes, the ballad and the rondeau.

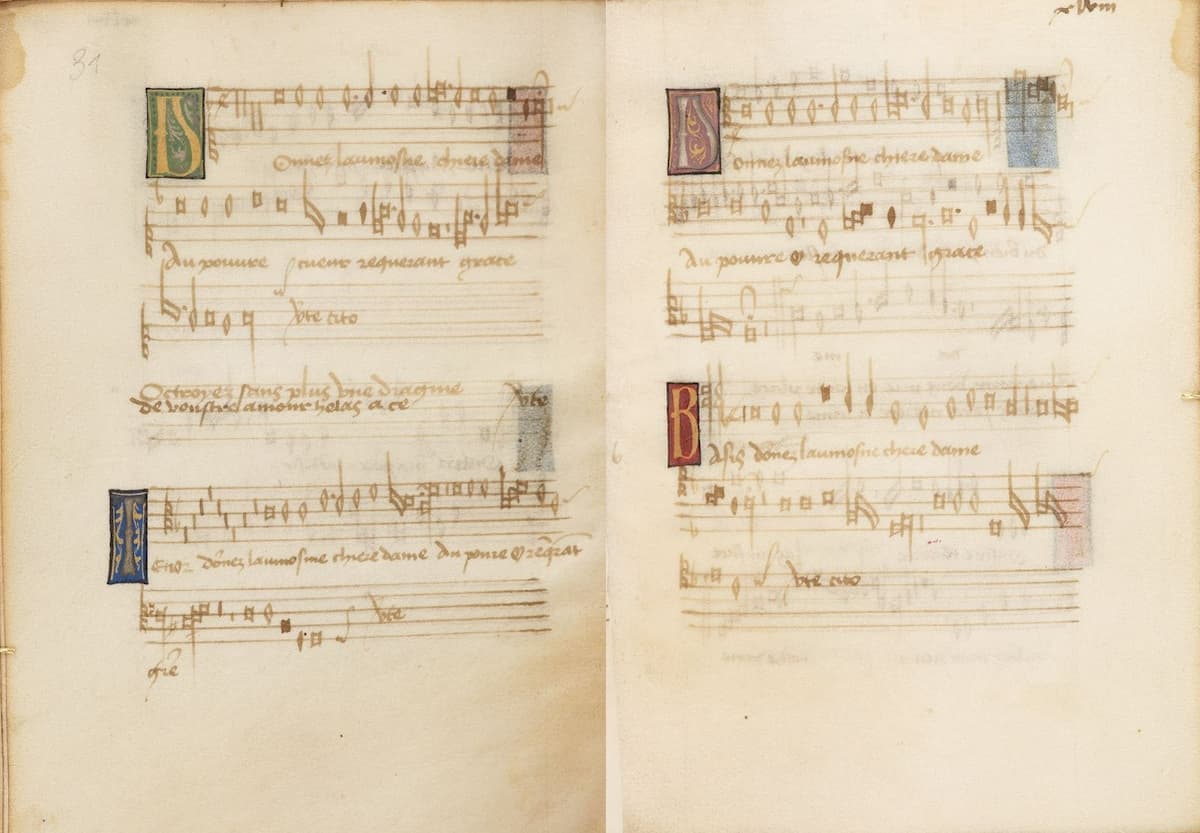

The Leuven Chansonnier: Donnez l’aumesne, fol. 47v, 48r

The only 4-voice piece of the unica is Donnez l’aumesne. The song begins with a monotone, imitating a beggar, and then the lover is compared to him (Give alms, dear lady, to the poor heart seeking grace…). This kind of program music, where the text is reflected in the music is extremely rare. It has been suggested that this might be a piece by Busnoys, whose music has many of the qualities found here: ‘its rich four-voice texture, sure-footed pacing, and strong harmony. …the text’s clever use of assonance suggests an accomplished poet; Busnoys was certainly that.’

Anonymous: Donnez l’aumosne, chiere dame] (arr. for 6 voices, vielle, viola d’arco and lute) (Els Janssens-Vanmunster, Tessa Roos; Grace Newcombe, discantus; Jacob Lawrence, Marc Lewon, Marc Mauillon, tenor; Raitis Grigalis, contratenor; Baptiste Romain, Renaissance violin; Elizabeth Rumsey, viola d’arco; Marc Lewon, lute and cond.)

Another interesting thing about Donnez l’aumosne is that the first measure of the contratenor part is a quotation from a very famous work by Johannes Ockeghem, Ma maistresse. This quotation is repeated through other voices in the first phrase.

Johannes Ockeghem: Ma maistresse et ma plus qu’aultre amye (arr. for vielle, viola d’arco and lute)(Baptiste Romain, Renaissance violin; Elizabeth Rumsey, viola d’arco; Marc Lewon, lute and cond.)

Ockeghem’s influence in the manuscript is plainly seen: some works use direct quotes from his texts, others are close imitations of the music from some of his famous pieces. These are the modern puzzles – scholars weigh the evidence, look at the music, and try to make connections between people and places. Perhaps another chansonnier will appear that gives attributes to the 12 anonymous unica, until then, we can just read, and listen, and try to fit the puzzle together.

See the full Leuven Chansonnier

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter