Helen Grime: 3 Whistler Miniatures

Called a ‘millionaire Bohemienne’ by a Boston reporter, the wealthy Isabella Stewart Gardner (1840– 1924) founded a museum that can be seen as the ultimate goal of any 19th-century traveller. After the death of her 1-year-old son from pneumonia in 1867, she was taken on a grand tour of northern Europe and Russia by her husband Jack. Other trips followed, such as Egypt and Middle East in 1874–1875 and Asia in 1883–1884.

Dennis Miller Bunker: Isabella Steward Gardner, 1889 (Boston: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum)

Living in Boston, she was drawn to the city’s intellectual life and, in 1878, attended the lectures of Charles Eliot Norton, professor of art history at Harvard University. Under his guidance, she began to collect rare books and manuscripts.

A visit to Venice and the Palazzo Barbaro, owned by fellow Bostonians Daniel and Ariana Curtis, inspired the creation of her own museum in Boston. The Palazzo Barbaro was the centre for American and English expats, including the painters John Singer Sargent, James McNeil Whistler. The Curtises had Bernard Berenson as their artistic advisor, and Gardner soon had his help in advising her on art and helping to facilitate the purchase of masterpieces.

After Jack Gardner’s sudden death in December 1898, Isabella continued with their plans to create a museum. Construction started in 1899 and was completed in 1901. Isabella lived in the museum on the 4th floor and spent 1901 and 1902 installing her collection of paintings, sculptures, tapestries, furniture, manuscripts, rare books, and decorative arts. There was a grand opening on 1 January 1903 of what has been called ‘one of the finest private art collections in America’.

Gardner not only exhibited her art collection but also organized concerts, lectures, exhibitions, and encouraged artists to work in the museum. Upon her death in 1924, she left the museum with an endowment and the stipulation that nothing in the galleries should be changed, and no art was to be sold from the collection nor new art acquired.

The Gardners met the artist James MacNeill Whistler (1834–1903) when they were in London in 1879. The writer Henry James introduced Whistler to the Gardners, who were travelling with their three nephews.

Whistler: Self-Portrait, ca 1872 (Detroit Institute of Arts)

Isabella Gardner sat for her portrait with Whistler in 1886, and it was the first of his works she acquired.

The Little Note in Yellow and Gold takes its naming convention from the musical line that Whistler frequently used, with music titles such as Nocturne, Harmony, and Arrangement used frequently. The painting known informally as Whistler’s Mother, for example, has the more formal title of Arrangement in Grey and Black, No. 1, Portrait of the Artist’s Mother.

In this little pastel, Whistler has caught a vibrant and fashionable beauty almost in motion. She holds back her wrap with her right hand while her left hand rises to hold the other end.

Whistler: The Little Note in Yellow and Gold, 1996 (Boston: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum)

In her music, Scottish composer Helen Grime (b. 1981) created a piano trio to capture the promise inherent in the drawing. Grime’s 2011 work isn’t programmatic in that the picture itself has no program. Just as Whistler’s lines flicker in and out of light and shade, so do Grime’s musical lines.

Helen Grime: 3 Whistler Miniatures – I. The Little Note in Yellow and Gold (Mithras Trio)

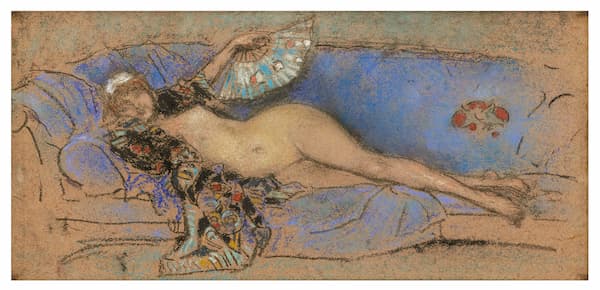

The next painting, Lapis Lazuli, depicts a reclining nude. Her kimono has fallen away in a wash of back, red, and green, and she holds an open fan. The Japanese references in the image were common with Whistler. Whistler’s signature, in a distinctive butterfly-shaped pattern, is prominent on the blue couch cover.

Whistler: Lapis Lazuli, 1886 (Boston: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum)

The music for this movement is much more fraught and active. We’re no longer in the world of the wealthy Boston socialite, but now in the world of the professional model. The music scurries and pauses, inconsequential and pensive at the same time.

Helen Grime: 3 Whistler Miniatures – II. Lapis Lazuli (Mithras Trio)

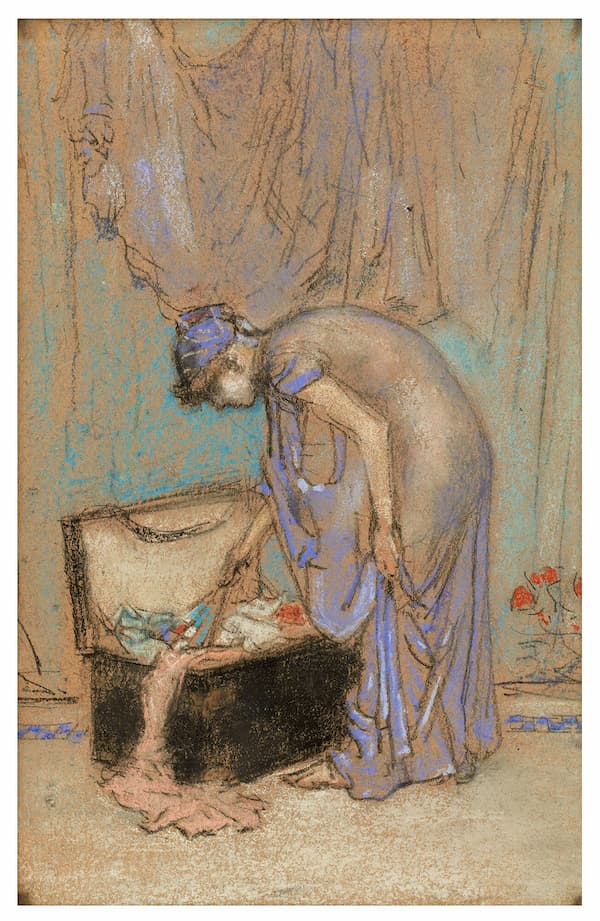

The third painting, The Violet Note, done at the same time as the other two, shows a model picking through a trunk of props and clothes, holding the same fan as the model in Lapis Lazuli held. The model is wearing a flowing covering in violet, with a striped, violet head scarf to match. In the bottom right corner is Whistler’s signature on the curtain.

Whistler: The Violet Note, 1886 (Boston: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum)

Grime’s start to this work is in the piano, with high, faint notes in the two strings. The complexity of each voice increases, and then fades away.

Helen Grime: 3 Whistler Miniatures – III. The Violet Note (Mithras Trio)

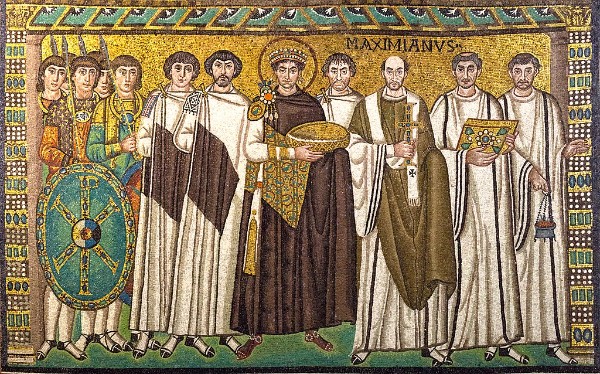

The three pictures hang in a row in the Veronese Room of the ISG Museum, just as Isabella placed them herself.

The East Wall of the Veronese Room (detail) (Boston: Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum)

The large painting above is Giovanni Tiepolo’s 1752 The Wedding of Frederick Barbarossa to Beatrice of Burgundy, and to the right of the three miniatures is another Whistler work, the oil painting The Sweet Shop, Chelsea, which also dates from 1886.

The three miniatures are all done with chalk and pastel on brown paper, and the brown paper plays its own role in the drawings. In the first drawing, it’s the backdrop against which Mrs. Gardner stands. In Lapis Lazuli, it’s not only the background and the couch but also the model’s base skin tone. In The Violet Note, the brown paper is part of the curtains and not really part of her skin tone. It peeps in and out of her violet covering, especially as it reaches the floor. Whistler’s use of both colour and no-colour, i.e., the colour of the paper itself, gives an extra dimension to these drawings.

The works are small, rather like a folded piece of paper: The Little Note in Yellow and Gold: 27 x 14 cm (10 5/8 x 5 1/2 in.); Lapis Lazuli: 13 x 26 cm (5 1/8 x 10 1/4 in.); The Violet Note: 26 x 18 cm (10 1/4 x 7 1/16 in.). Grime’s piano trios are similarly condensed. She makes each movement as distinctive as the original art, conveying what’s behind the image: a gracious society matron, an exposed model, and a model choosing her setting. They are all images of 19th-century life at different levels. The drawings are intimate, increasingly so across the series, and Grime picks up those levels, giving us a view of three very different women. The violin, cello, and piano each provide different textures and enter and fade away, just as Whistler’s lines.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter