David Leisner: Dances in the Madhouse

George Bellows

American realist painter George Bellows (1882–1925) is best known for his realist paintings of New York City.

Before that, while still in his student years in the Midwest, he made a drawing based on his visits to the local state mental hospital in Columbus, Ohio. In the drawing, he captures a set of vignettes of the interactions of the inmates dancing. But, by placing the figures in a dim and dark dance hall and using very dark tones, we have an image with a rather ominous frivolity. This was later used as the basis for a lithograph a decade later.

Bellows: Dance in a Madhouse, drawing, 1907 (Art institute of Chicago)

Bellows: Dance in a Madhouse, lithograph, 1917 (National Gallery of Art)

The influence on the work has been traced back to Francisco Goya’s painting form 1794, La casa di locos (The Madhouse), which also depicts an asylum with people in various states of madness. Note the Piranesi-like use of a single high light source and the high walls that emphasize the prison atmosphere.

Goya: Casa de locos, 1812-19819 (Madrid: Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando)

In lithography, the artist draws directly on the printing stone with a pencil made of grease and lamp black. His 1907 drawing, done while visiting a friend who was the superintendent at the Ohio State Mental Hospital. He visited during their social hour and captured his experience in a drawing.

He described his experience:

For years the amusement hall was a gloomy old brown vault where on Thursday nights the patients indulged in “Round Dances” interspersed with two-steps and waltzes by the visitors. Each of the characters in this print represents a definite individual. Happy Jack boasted of being able to crack hickory nuts with his gums. Joe Peachmyer was a constant borrower of a nickel or a chew. The gentleman in the center had succeeded with a number of perpetual motion machines. The lady in the middle center assured the artist by looking at his palm that he was a direct descendant of Christ. This is the happier side of a vast world which a more considerate and wise society could reduce to a no[t] inconsiderable degree.

In Bellows’ lithograph, light, coming from behind the viewer is used to illuminate the figures. In the far back left corner, a conductor lifts his hands to lead the small band. The background of the room offers shadowy details of the fittings: windows, wainscoting, and pilasters, giving the impression of a room with more than bare walls.

In the center, a couple dances and the woman leans dangerously back to leer at the viewer, kept up only by her partner’s grip. To their right, a man gestures emphatically to his much shorter dance partner, his face angled to catch the light. Behind him, a woman dances by herself, partnerless, caught up in her own memories. On the bench to the right there are a variety of emotions. One woman holds her head in her hands, perhaps in despair, and another just sits, thinking. The woman behind them, to the extreme right of the painting, stare out, frozen faced, at the viewer. Many of the faces seem mask-like or even grotesquely exaggerated, another link to Goya.

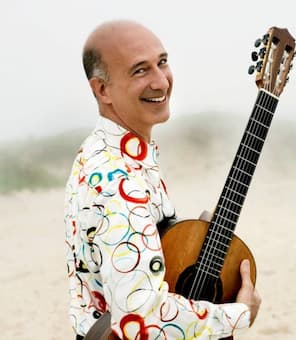

David Leisner

American guitarist and composer David Leisner was commissioned by guitarist John Schneider for a piece for violin or flute and guitar and Leisner was inspired by Bellows’ lithograph to create his own Dances in the Madhouse.

Each movement of the work focuses on a different group in the image, starting with Tango Solitaire, which creates a dance for the solitary woman in the centre. In the image she has her arms held high, as in tango style, but her partner is only in her head. And the music, too, seems lonely and lacking that strong tango rhythms. Perfect for someone who is dancing in place.

David Leisner: Dances in the Madhouse – No. 1. Tango Solitaire (Cavatina Duo)

Next, it’s a Waltz for the Old Folks, who stand in front of the single woman dancing. Their waltz is also slightly off. No strict 1-2-3 for them, but it’s music with time for gestures and pauses and perhaps a bit of footwork as well.

David Leisner: Dances in the Madhouse – No. 2. Waltz for the Old Folks (Cavatina Duo)

The Ballad for the Lonely is directed at the two women who sit on the bench, each with their own problems – one in utter despair and the other lost in her thoughts. Each voice, the flute and the guitar, seem occupied with their own melodies, the flute flowing from idea to idea, while the guitar pursues a more definite track.

David Leisner: Dances in the Madhouse – No. 3. Ballad for the Lonely (Cavatina Duo)

Leisner chose the wild couple in the middle for his last movement, Samba! The music flows and the dancers whirl, barely seeming to be able to keep to their feet.

David Leisner: Dances in the Madhouse – No. 4. Samba! (Cavatina Duo)

Bellows’ lithograph captures a difficult time in the American psyche – the patients are locked away from society, yet, during their weekly dance evenings, were still supposed to play out some idea of normalcy. Bellows shows the lie behind the idea where no one in the entire room dances normally. They dance alone, or in pairs that seem to be dancing two different dances at the same time. Perhaps it’s the two women on the bench who capture it best – just sit and think, and not even watch the semblances of the world around you.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter