Inspirations Behind Aaron Jay Kernis’s Invisible Mosaic Series

A mosaic uses small pieces of glass, coloured stone, or ceramic to create a larger pattern or image. First found in Mesopotamia in 3000BC, they spread through the world and can be found in Ancient Greece and Rome. They were used to create wonderful pictures. They were usually done on walls and floors, where they were beautiful and traffic-resistant.

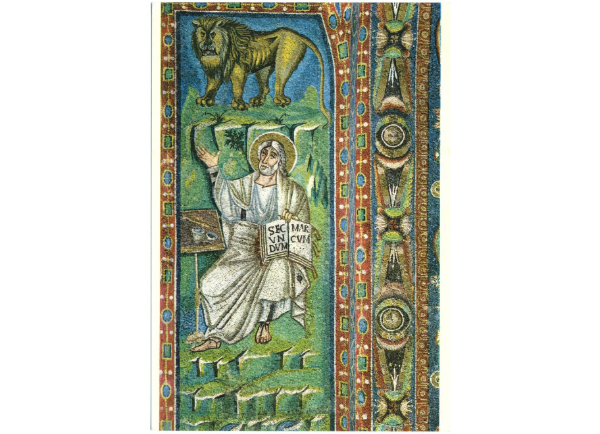

The Basilica of San Vitale, in Ravenna, Italy, consecrated in 547, holds one of the most famous and important examples of early Byzantine art. The ambulatory, the processional way around the east end of the church, is on two levels. The mosaics used there cover many of the themes and images from the Old Testament, including ‘the Hospitality of Abraham (Genesis 18:1-16), and the Sacrifice of Isaac; the story of Moses and the Burning Bush, Jeremiah and Isaiah, representatives of the twelve tribes of Israel, and the story of Abel and Cain’. There are also mosaics of the Evangelists Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, and their symbols, the angel, lion, ox, and eagle.

Saint Mark and his lion

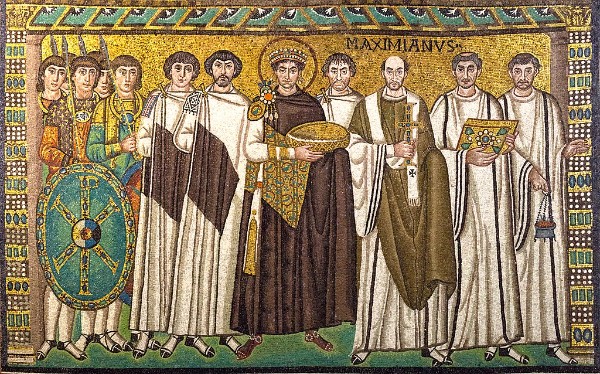

One of the most famous mosaic panels depicts ‘the East Roman Emperor Justinian I, clad in Tyrian purple with a golden halo, standing next to court officials, generals Belisarius and Narses, Bishop Maximian, guards and deacons’.

Mosaic of Emperor Justinian and his retinue (Photo by Roger Culos)

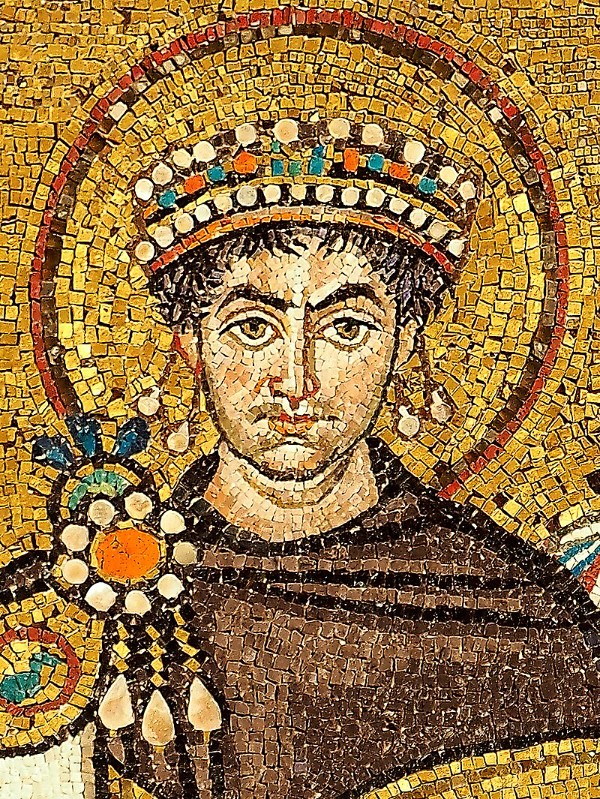

Mosaic of Justinian I (detail)

Opposite this is the other famous panel, that of the Empress Theodora.

Empress Theodora and attendants (photo by Petar Milošević)

Mosaic of Theodora (photo by Petar Milošević)

Where the mosaics used for the Emperor and Empress images seem to be large, small details were also possible in the format.

See, for example, the lamb at the centre of the presbytery ceiling in detail and then in position, which shows subtle colour transformations in it.

Presbytery lamb detail (Photo by Sailko)

Full presbytery mosaic (photo by Petar Milošević)

American composer Aaron Jay Kernis (b. 1960) was in Ravenna and saw the mosaics in 1984. ‘Noting the artists’ virtuosity in constructing gigantic and vivid images out of thousands of fragments of coloured tile, he was inspired to use an analogous process in his music, building up a large structure through the patterning and layering of tiny fragments, creating a mosaic of music.

Aaron Jay Kernis

It sounds at the opening like a puzzle spilled across the floor. In writing about the compositional process of creating the work, Kernis said that after he first saw the mosaics, he ‘had a series of vivid hallucinations which were brought on by their densely coloured, fragmented surfaces. Initially I was overwhelmed, seeing only whirling, broken-up fields of colour devoid of form or figuration. It was like being thrown into a room with a million flashing, multi-coloured lights which completely overtook the senses’. This prompted him to write his Invisible Mosaic series.

Invisible Mosaic I (1986) was commissioned by the Tippett Foundation and the Dartington International School of Music in Devon, England, and was written for clarinet, violin, cello and piano.

In 1988, Invisible Mosaic II for large ensemble was written for the Ensemble Intercontemporain in Paris, and, later that year, Invisible Mosaic III, for orchestra, was composed for the American Composers Orchestra.

Aaron Jay Kernis: Invisible Mosaic II (The New Professionals; Rebecca Miller, cond.)

The images of the mosaics themselves are static – there’s no motion, no movement, they’re just images of people and concepts. In his music, however, Kernis starts with the creational process of the mosaics themselves. The individual colours and sounds of the instruments stand for the individual colours and sizes of the mosaic pieces.

From the beginning swirl of sound and colour, the sound image gradually comes together. In places, the base does a slow ascent while above it the woodwinds and strings twitter and move. He uses irregular metre, switching from 7/16 to 5/16 to 6/16 to 8/16, and 3/4 to 4/4, changing from measure to measure in some sections.

When looked at too closely, the images in the mosaic vanish. It’s only with distance that we can achieve the vision of the religious portraits. So it is with Kernis’ work, the individual lines are idiosyncratic for each instrument, but taken together, the majesty of the whole is revealed.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter