Adolphe Sax

The Belgian instrument maker Adolphe Sax (1814-1894) was the son of instrument designer Charles-Joseph Sax. Adolphe began to design instruments in his youth, specializing in the flute and the clarinet before going on to the Royal Conservatory in Brussels.

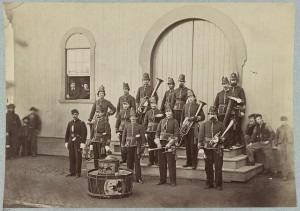

He moved to Paris in 1841 and began working on new instruments. In 1844, he worked on valved bugles, and his examples were so successful, that all valved bugles, whether made by Sax or not, were called Saxhorns. Because these were based on the bugle, the instrument has a conical bore, i.e., from the narrowest part at the mouthpiece to the widest part at the bell, the instrument gets gradually wider. During the American Civil War, an over-the-should variety was developed so that the band, which marched in front of the army, could pay for the men behind them. When you look at this picture of a band from 1865, you’ll see that when they put their instruments to their lips, the bells of the instruments will point backwards.

Civil War Band, 1865

The instrument he was seeking to replace was popular at the time, but now is no longer part of the common instrument families: the ophicleide. The Ophicleide is a conical-bore instrument made in metal, with keys like the woodwinds, but which is played using a metal mouthpiece, similar to that of a trumpet. It was extremely difficult to play, hard to keep on pitch, and with a rugged sound.

In his groundbreaking 1988 recording of Berlioz’ Symphony fantastique, Roger Norrington used the ophicleide to underscore the horror of the use of the ‘Dies Irae’ in the final movement of the work – listen at 03:28 where you hear a sound (after the un-tuned bells) that’s not a trombone or a euphonium or a tuba –but something wilder.

Berlioz: Symphonie fantastique: V. Songe d’und Nuit du Sabbat. London Classical Players, Roger Norrington, cond.

In concert bands, the saxophone has a ready place, as it also does in jazz bands. In the orchestra, however, the sax has a rare place in 19th century music, and mainly appeared in music by French composers. It’s used in one movement of Ravel’s orchestration of Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, in The Old Castle, where it is supposed to represent a troubadour singing – the element that Sax built into the instrument, the singing quality, comes through in this work.

Saxophone

Unfortunately, that’s the only music for the saxophone during the entire work, so the player has to sit there, silent, for the rest of the concert.

In the 20th century, there has been more music on the orchestral stage for Saxophone, particularly as popular music has had more of an influence. Here’s a modern Japanese composer, Takashi Yoshimatsu, and his saxophone concerto entitled “Cyber-bird.” The jazz influences are clear in this 1993, but then again, so is the ability of the saxophonist to take flight as a bird on the wings of his instrument.

Yoshimatsu: Saxophone Concerto, Op. 59, “Cyber-bird” Nobuya Suaga, sax, BBC Philharmonic Orchestra, Sachio Fijioka, cond.

In displacing the ophicleide as an instrument of the French Army, the saxophone securely Adolphe Sax a nice contract and the money to match. He might have been driven into bankruptcy more than once because of the lawsuits of rival instrument makers, but it is still his instrument, with his name on it, that we still know, more than 200 years after his birth, and years after he was granted the patent, for which we remember Adolphe Sax.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter