Believe it or not, the dictionaries and most prominent reference books of 1878 did not have a word to identify what we now think of as abstract art. The best anybody could do at the time was to compare paintings to work of music, and specifically to works of absolute music like the symphony or the nocturne. It was left to the German architect August Endell (1871-1925) to distance art from a slavish imitation of nature. He was looking to define an art that “was based on a feeling of pleasure and on the pure joy of form and color.” Endell had studied philosophy, psychology, and mathematics at Munich University, but in the end became a self-taught architect and applied artist. Endell received his first commission in 1897, which practically made him famous overnight. His design for the façade of the Atelier Elvira Photographic Studio in Munich featured a red and golden dragon-like stucco ornament on a green background. Although officially named “Octopus Rococo,” the design was sharply criticized and mockingly referred to as the “Dragon’s Castle,” or the “Chinese Embassy.”

Believe it or not, the dictionaries and most prominent reference books of 1878 did not have a word to identify what we now think of as abstract art. The best anybody could do at the time was to compare paintings to work of music, and specifically to works of absolute music like the symphony or the nocturne. It was left to the German architect August Endell (1871-1925) to distance art from a slavish imitation of nature. He was looking to define an art that “was based on a feeling of pleasure and on the pure joy of form and color.” Endell had studied philosophy, psychology, and mathematics at Munich University, but in the end became a self-taught architect and applied artist. Endell received his first commission in 1897, which practically made him famous overnight. His design for the façade of the Atelier Elvira Photographic Studio in Munich featured a red and golden dragon-like stucco ornament on a green background. Although officially named “Octopus Rococo,” the design was sharply criticized and mockingly referred to as the “Dragon’s Castle,” or the “Chinese Embassy.”

Endell described his creative technique in the following way. “The starting point for my work was the embroideries of Hermann Obrist, in which I got to know for the first time free organically discovered, not externally composed, forms. At first I studied purely as a psychologist and aesthetic theorist until I was gradually convinced that it must be possible to achieve strong and living effects in architecture and applied art exclusively through freely invented forms. After many experiments and a series of practical works, I was sure of myself and began to work systematically in this way.“ Testing organic formations for psychological impact, Endell believed himself able to avoid the mistakes he found in the works of other artists. In the year of the Atelier Elvira commission, Endell also published his enormously influential essay “Beauty of Form and Decorative Art.” Focusing on architecture and decorative art, Endell openly called for “the beginning of a totally new art, an art with forms that mean nothing and represent nothing and remind one of nothing; yet that will be able to move our souls so deeply, as before only music has been able to do with tones.” The idea was for art to exploit “the power of form on our feelings, a direct, immediate influence, without any mediation.” Just like music, which can be enjoyed “without knowing why chords and progressions are in a position to stimulate us so powerfully.”

Endell described his creative technique in the following way. “The starting point for my work was the embroideries of Hermann Obrist, in which I got to know for the first time free organically discovered, not externally composed, forms. At first I studied purely as a psychologist and aesthetic theorist until I was gradually convinced that it must be possible to achieve strong and living effects in architecture and applied art exclusively through freely invented forms. After many experiments and a series of practical works, I was sure of myself and began to work systematically in this way.“ Testing organic formations for psychological impact, Endell believed himself able to avoid the mistakes he found in the works of other artists. In the year of the Atelier Elvira commission, Endell also published his enormously influential essay “Beauty of Form and Decorative Art.” Focusing on architecture and decorative art, Endell openly called for “the beginning of a totally new art, an art with forms that mean nothing and represent nothing and remind one of nothing; yet that will be able to move our souls so deeply, as before only music has been able to do with tones.” The idea was for art to exploit “the power of form on our feelings, a direct, immediate influence, without any mediation.” Just like music, which can be enjoyed “without knowing why chords and progressions are in a position to stimulate us so powerfully.”

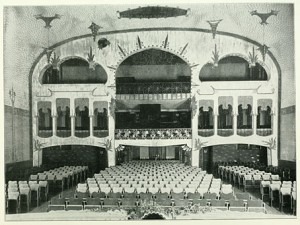

Endell very persuasively explained how in architectural design, a straight line can have musical effects upon our feeling and perceptions through direction and tempo. In a series of rectangular window designs, he demonstrated that when a horizontal line subdivides a window, the tempo becomes slower. “The level of tension depends on whether one is viewing the window from top to bottom or bottom to top; the latter creates greater tension.” Barely a year later, Endell forcefully repeated the analogy between form-art and music in an essay entitled “The Beauty in the Big City.” He wrote, “There is an art that no one seems to know about: Form-art, which bubbles up out of the human soul only through forms.” Endell did not invent the interpretation of architecture or of visual linear motion in musical terms, however it was his critical discourse that accelerated the move towards nonobjective art. And of course, he translated his theories into actual architectural spaces. The Buntes Theater (Colorful Theater) in Berlin was completed in 1901, and quickly followed by the Hackesche Höfe, a notable courtyard complex in the center of Berlin. He even created the first artistic racecourse architecture in 1913. Endell was a visionary pioneer in creating visual art and works of art that were architecturally structured, however still expressed the qualities of other forms of art.

Endell very persuasively explained how in architectural design, a straight line can have musical effects upon our feeling and perceptions through direction and tempo. In a series of rectangular window designs, he demonstrated that when a horizontal line subdivides a window, the tempo becomes slower. “The level of tension depends on whether one is viewing the window from top to bottom or bottom to top; the latter creates greater tension.” Barely a year later, Endell forcefully repeated the analogy between form-art and music in an essay entitled “The Beauty in the Big City.” He wrote, “There is an art that no one seems to know about: Form-art, which bubbles up out of the human soul only through forms.” Endell did not invent the interpretation of architecture or of visual linear motion in musical terms, however it was his critical discourse that accelerated the move towards nonobjective art. And of course, he translated his theories into actual architectural spaces. The Buntes Theater (Colorful Theater) in Berlin was completed in 1901, and quickly followed by the Hackesche Höfe, a notable courtyard complex in the center of Berlin. He even created the first artistic racecourse architecture in 1913. Endell was a visionary pioneer in creating visual art and works of art that were architecturally structured, however still expressed the qualities of other forms of art.

Kurt Weill: Cello Sonata

More Arts

-

Musicians and Artists: Adams and Rothko Transforming Mark Rothko's color field painting into music

Musicians and Artists: Adams and Rothko Transforming Mark Rothko's color field painting into music -

Musicians and Artists: Gould and Burchfield Morton Gould's musical tribute to artist Charles Burchfield

Musicians and Artists: Gould and Burchfield Morton Gould's musical tribute to artist Charles Burchfield -

Musicians and Artists: Greenbaum and Escher Discover how Escher's visual paradoxes inspired Australian composer Greenbaum

Musicians and Artists: Greenbaum and Escher Discover how Escher's visual paradoxes inspired Australian composer Greenbaum -

Musicians and Artists: Schurmann and Bacon Inspirations behind Gerard Schurmann’s 6 Studies of Francis Bacon

Musicians and Artists: Schurmann and Bacon Inspirations behind Gerard Schurmann’s 6 Studies of Francis Bacon