The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) is the largest art museum in the Western United States, holding a collection of more than 142,000 objects. We’ll continue our museum ramblings in through this wide-ranging collection that covers more than 6,000 years of international artistic expression.

We’ll start with a work with a punning title. As children, we played Musical Chairs, where 10 children ran around 9 chairs hoping to be able to sit when the music stopped. In his 1990 sculpture, American artist Steven Hold created his own Musical Chair, but one where the music is part of the chair.

Created out of SurellTM, a solid surfacing material, the chair sits solidly on 4 legs. On the right side, a protruding handle might turn a cylinder where a melody is coded on protruding pins. The back of the chair is made of the comb that the pins on the cylinder hit and make sound. This chair-sized musical box is the beginning of what Hold called his ‘Post-Credible’ style. Part of Post-Credible style is the juxtaposing, mingling, and merging of specific object qualities. In this case, he’s merged a music box and a generic chair to create his Musical Chair, which is nether musical nor, probably, a very comfortable chair.

Steven Hold: Musical Chair, 1990 (LACMA)

Friedrich Silcher: Verlorenes Glück, Op. 68, No. 2 (arr. for music box)

In this painting by French artist Martin Drölling entitled Painting and Music, we have the artist’s son putting aside his vioin and music to gaze out the window. Inside, a young woman, her mahl stick in hand, paints a landscape with a barn. Outside the window, a small bird is in a cage, representing natural music where the written music and the violin embody created or art music. The hand-made rug versus the crawling ivy is another opposite. We could also see the irony in the outdoor picture being created in a dark room while the musician stares outside for inspiration. This style of picture where the subject seems almost to lean out of the window and enter the room of the viewer was common in Drölling’s output.

Martin Drölling: Painting and Music (Portrait of the Artist’s Son), 1800 (LACMA)

Edvard Grieg: Lyric Pieces, Op. 43: No. 4, Vöglein (arr. V. Godar) (Takako Nishizaki, violin; Jenő Jandó, piano)

After starting his career in Rome and emulating the chiaroscuro style of Caravaggio, Nicolas Regnier moved to Venice in 1625 and completely changed his style to one of light and brilliancy. Venice in the 17th century was known as the ‘Republic of Music,’ and visitors reported that every household made music. Opera was the new musical form of the day and the instrumental ensemble found its new place. In this ensemble, two women, one crowned with a laurel wreath, is among a feast of stringed instruments. There are two violins, a viola da gamba, a theorbo (a long-necked lute), and another instrument of which we can only see the back. The woman on the right has just put down her bow while the woman on the left points to heaven, the source of all musical inspiration. Music books are scattered around the table along with a rolled-up picture of a small child holding an instrument that might be a lyre.

Nicolas Regnier: Divine Inspiration of Music, ca. 1640 (LACMA)

Claudio Monteverdi: Quel sguardo sdegnosetto (Susanne Rydén, – soprano; William Dongois, cornetto; Peter Croton, lute; Björn Gäfvert, organ)

In his painting L’Accord parfait (The Perfect Accord), Jean-Antoine Watteau takes us back into his world of parks and processions. Here, a young woman holds open a book of music for a flutist, while at her feet, his back to the viewer, a man in a striped pink and blue costume gestures with his left hand. Behind the trio, a couple strolls away.

Jean-Antoine Watteau: L’Accord parfait (The Perfect Accord), ca. 1719 (LACMA)

Jean-Baptiste Lully: Le Triomphe de l’Amour – Ritournelle pour Diane (Barthold Kuijken and Immanuel Davis, traverse flutes; Arnie Tanimoto, viola da gamba; Donald Livingston, harpsichord)

In this musical party of the 1620s, French painter Valentin de Boulogne gives us a metaphor for time. The woman beats her tambourine to the passing of time while men of four different ages surround her. Youth on the violin, the adolescent on his lute for love, soldier in armour drinking from a glass, and the old man in the middle playing a simple pipe. A part book is open in front of the lutenist. The poetic allusion to the ages of man and their activities comes out beautifully in this image, while at the back, time is measured and passes on.

Valetin de Boulogne: A Musical Party, ca. 1623-1626 (LACMA)

John Eccles: The Mad Lover Suite – Aire V – Ground (Théotime Langlois de Swarte, violin; Thomas Dunford, lute)

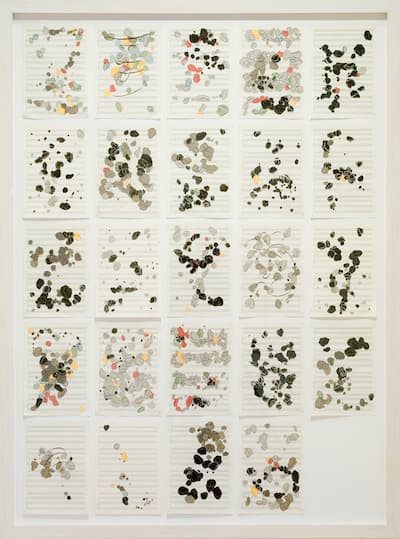

We know what music sounds like, but what does music look like on the page? For Mexican artist Pablo Vagas Lugo, he chose to combine music paper with rocks ‘derived from Chinese painting and Japanese anime.’ It looks like music but isn’t music. The 24 pieces are then placed in a frame to look like a musical score, but it can’t be played, no matter what title the artist puts on the work. His work borrows from a broad range of disciples ranging from astronomy to music and archaeology to cinematography. One of his themes is to show us the persistence of ancient traditions in unexpected costumes, here, the mix of anime and a visual aspect of music. The cutouts placed on music paper neither make this music nor do we understand what the rocks are saying.

Pablo Vargas Lugo: Ode to Joy/Requiem, 2005 (LACMA)

John Cage: Radio Music (Fausto Bongelli, Manuel Zurria, Fabrizio Ottaviucci, Mike Svoboda, Giovanni Damiani, electronics; Stefano Scodanibbio, cond.)

Wagner’s Tannhauser combined two different stories – the myth of Venus and the Venusberg, and a 14th century minnesinger contest. Wagner’s stage directions for the opening of Tännhauser are followed almost exactly in this painting by Fantin-Latour: “The stage represents the interior of the Venusberg… In the distant background is a bluish lake; in it one sees the bathing figures of naiads; on its elevated banks are sirens. In the extreme left foreground lies Venus bearing the head of the half kneeling Tannhäuser in her lap. The whole cave is illuminated by rosy light. – A group of dancing nymphs appears, joined gradually by members of loving couples from the cave. – A train of Bacchantes comes from the background in wild dance…” We may not have the bathing naiads, sirens or the procession of loving couples, and Venus is in Tännhauser’s lap rather than the reverse, but we do have what Wagner imagined his stage would be like in 1845. In this painting from 20 years later, we have a player of the aulos joined by a woman dancing with a tambourine, all symbols of the followers of Bacchus, the Bacchantes. Tännhauser leans on a harp, a symbol of his regular world profession of a singer.

Henry Fantin-Latour: Tannhäuser on the Venusberg, 1864 (LACMA)

Richard Wagner: Tannhäuser – Overture (Bayreuth Festival Orchestra; Axel Kober, cond.)

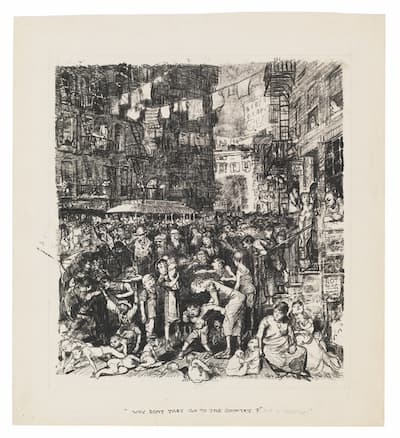

In the last picture we’ll look at, the music isn’t given to us through musical instruments or score paper but through the colour choices of the artist. George Bellows’ 1913 painting Cliff Dwellers was among the first paintings acquired by LACMA and is a strong representative of New York’s Ash Can School. The picture gives us a strong image of lower-class urban life at the turn of the century. It’s a hot summer’s day so everyone is on the street hoping for a breeze or some fresh air. During the summer, the wealthy of New York went to the country, but the poor didn’t have that possibility. This was shown in a drawing Bellows did for the progressive magazine The Masses this same year, entitled ‘Why Don’t They Go to the Country for Vacation?’, mocking the tone of the wealthy when confronted with the heat and hubbub of city life in the summer in the Lower East Side.

George Bellows: Why Don’t They Go to the Country for Vacation?, 1913 (LACMA)

The colour theorist Hardesty G. Maratta created a disciplined colour theme, based on colours and their complements, that was used by Bellows and others in the early 20th century. In this picture, we have three ‘chords’ that are created through colour:

Chord 1: Orange – Red-Purple – Green-blue

Chord 2: Blue-Purple – Green – Red-orange

Chord 3: Yellow-Green – Red – Blue

These are triads of complementary colours that were used, like the notes of a scale, to establish a particular harmony or mood. When you first look at the painting, the light, angling in from the bottom left corner, draws your eyes to the centre right back, where the light hits the building on the next block. When you start to examine this through the colour chords, you can see that the produce wagon is in the first chord and those same colours can be seen through the lower section of the crowd in its orange hair, green clothes, blue shadows, etc.

The second chord is in the shadowed building at the left, with its green shutters and red brick wall, moving to the blue-purple at the right.

The third chord is in the lighted building at the back center, particularly with its yellow-green elements on the shutters. The red and blue are at the roof level.

These chords help us move through the painting, just as we noted with how the light moves our eyes through the work, the chordal colour choices help as well. The bright orange in the lower left has become a faded brick red at the top right.

George Bellows: Cliff Dwellers, 1913 (LACMA)

Leonard Bernstein: On the Town: 3 Dance episodes: No. 3. Times Square: 1944 (Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra; Marin Alsop, cond.)

We’ve seen music used for its punning quality in a sculpture that’s neither musical nor a chair, in a score that’s unreadable, and in beautiful set pieces that show music as a metaphor for culture, for the ages of man, and for love. In Bellows’ social commentary, its visual chords, not audible ones, that drive the art.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter