The Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA) was founded in 1885 and benefitted from the Detroit philanthropists such as the Dodges, the Firestones, and the Fords, i.e., the leaders of the American automotive industry, known collectively as the Auto Barons. Charles Lang Freer, another early Detroit automotive chief, was the start of the collection, but when he died, the rest of his collection went to the Smithsonian Institution to become the core of their Freer Gallery of Art.

The DIA is the fifth largest art museum in the United States with a collection that spans ancient Egyptian art to today’s contemporary scene.

We’ll start looking at two paintings by the mid-18th century artist Filippo Falciatore. They were both completed ca. 1750 and can be viewed from the point of view of different social level’s approach to music. In the first, Concert in a Garden, a servant on the left in a brown coat, brings frothing drinks out to a party being entertained by a harpsichordist, centre, and a violinist in red. The men and women around them flirt and carry on. The woman on the left points at the keyboard with her fan while on the right, another woman shields herself from others’ gaze with her fan. Love is in the air and the man in black at the end of the harpsichord looks out at the audience with a frown on his face from all the goings-on.

To make this work within the plane of the picture, the harpsichord had to be given a highly unlikely curve in its side, which would have had the effect of making it impossible to play, as the strings couldn’t possibly sound in that position. That our attention should be on the harpsichordist rather than on the violinist, despite his bright red coat, is emphasized by placing the violinist behind the harpsichord, rather than his more usual place in front of it.

Filippo Falciatore: Concert in a Garden, ca. 1750 (DIA)

Joseph Bodin de Boismortier: Flute Sonata No. 3 in G Major, Op. 91 – I. Rondement – Gayement (Stephen Schultz, flute; Byron Schenkman, harpsichord)

In the other picture, Tarantella at Mergellina, we are in Naples, where the two central figures are dancing to music played on a very oddly shaped lute and a large tambourine. The tarantella may have originated in ancient rites concerning spider bites, but in 18th century Naples, the tarantella was a courtship dance performed by couples to music that grows increasingly faster. The dance to cure one from a tarantula spider bite was for a single dancer, while this dance is clearly for two.

Filippo Falciatore: Tarantella at Mergellina, ca. 1750 (DIA)

Anonymous: Tarantella napoletana [Hannover, Stadtbibliothek, mss. Herman Kestner 125] (T Liuwe amminga, organ; Fabio Tricomi, cond.)

What’s the societal difference between the two pictures, painted around the same time? In the upper-class one, we’re in an elegant garden that’s built around some scenic ruins. The few people in working-class garb are constrained to the edges of the image, peering over a wall, or working in the garden, or serving snacks. In the lower-class image, we’re again by a ruin, but now in the middle of the fish market. Our dancers are not just visible to their few friends, but here are in full view of the world. While they dance, business is conducted on the left by one fishwife while another on the right watches from her chair. Behind her, two fishermen comment on the action and behind the players, a woman suckles her child. In the first picture we have private courting couples and in the second, we have public courtship dances and the result of that dance.

From the mid-18th century, we’ll leap forward to the late 19th century. In Edgar Degas’ Violinist and Young Woman, we have two people caught mid-action. He’s tuning his violin, fingers poised on the tuning peg as he listens to the plucked pitch, and she’s holding a book, perhaps of music. It’s as though they were interrupted mid-action and have turned to look at what disturbed them. Both of their faces are distinctive, although their identities are not known today, while their clothes and the music book are only loosely sketched in. We can see that he’s not ready to play not only because we see him tuning his instrument but also because his violin bow is nowhere to be seen.

Edgar Degas: Violinist and Young Woman, ca. 1871 (DIA)

Maurice Ravel: Tzigane (arr. Y. Bandoh for violin and chamber ensemble) (Ami Oike, violin; Ensemble FOVE)

Orazio Gentileschi gives us a dramatically lit image of a Young Woman with a Violin, which has traditionally been interpreted as am image of Saint Cecilia, the patron saint of music. Typically, Saint Cecila is shown playing an organ, a more traditional instrument for playing in a church, but Gentileschi, who may have used his daughter, the painter Artemisia Gentileschi, as a model, has chosen a more unusual instrument. She has her bow at the ready and looks heavenward, as if seeking her cue. The raking light highlights her face but, curiously, leaves no shadow from the violin. The realism in the portraiture is thought to have come to Gentileschi from the influence of Caravaggio, whose many music paintings always seem, like this one, to catch players mid-performance.

Orazio Gentileschi: Young Woman with a Violin (Saint Cecilia), ca. 1612 (DIA)

Jean-Marie Leclair: Violin Sonata in E Minor, Op. 2, No. 1 – I. Adagio (Adrian Butterfield, baroque violin; Jonathan Manson, viola da gamba; Laurence Cummings, harpsichord)

In Michiel van Musscher’s family portrait, entitled The Sinfonia, an unknown family gathers around a table, she feeds treats to her little King Charles spaniel, while he plays his bass viol, and a servant brings a plate of oranges. The floor is done in a striking black and white marble pattern. The woman wears a beautiful cream silk dress with jewels at the wrist and neck with a creamy green over scarf. She has a large pearl necklace at her throat and even larger pearl drop earrings. Her hair is done in fashionable ringlets. He wears a black suit with silver decorations and a brown scarf with long tassels at his waist. His hands are delicate but seem to know what they’re doing on his viol. His hair falls in long waves. The open music book on the table gives the name to the picture: it’s opened to page 12 to a work entitled “Sinfonia.” The servant is dressed plainly but well, and holds a dish of oranges, which could be a visual reference to the royal family, i.e., the House of Orange. The whole image is one of wealth and culture. The little dog, a favourite of England’s King Charles, is shown in its 17th century form with a long nose. The dog was later cross-bred with the pug to create a dog with a shorter nose. This picture, painted in 1671, captures the Dutch Golden Age, which was to end the next year when The Netherlands was nearly overrun by France as part of the Franco-Dutch War and the third Anglo-Dutch was behind a temporary naval blockade of the country by England.

Michiel van Musscher: The Sinfonia (Family Portrait), 1671 (DIA)

Michiel van Musscher: The Sinfonia (Family Portrait), detail, 1671 (DIA)

Georg Philipp Telemann: Sinfonia in F Major, TWV 50:3: I. Alla breve (Marion Verbruggen, reccorder; Sarah Cunningham, viola da gamba; Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment; Monica Huggett, cond.)

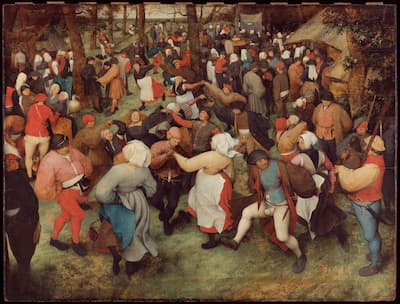

Going in back in time by a century, we see a different level of Netherland society. In this peasant wedding picture of 1566 by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, fancy curled hair is replaced by cloth head coverings on all. At the right, two bagpipers play and the wedding guests dance. The arms of the dancers are exaggerated in size to make this all seem clumsier. The dancers are wild and will all lead, as any contemporary moralist would tell you, to lustful behaviour and then sin and damnation. In the meantime, however, a great time is had by all.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder: The Wedding Dance, 1566 (DIA)

Arnold von Bruck: So drincken wir alle (Egidius Kwartet)

From the looks on the faces of the people peering into the room, The Boors’ Concert was probably less about a concert than about noise. David Teniers II’s painting captures the unique horror of two outside instruments, bagpipes and a hurdy gurdy, being played in a small room. The trio of singers can only add to the noise. Teniers II made other pictures of boors in taverns but this one has a unique sound quality that can only prompt one to run away.

Teniers was a painter and etcher and married Anna, the daughter of Jan Bruegel the Elder, with Rubens as witness. He worked in Brussels as court painter to Archduke Leopold Wilhelm in1651 and was a founding member of the Antwerp Academy of Art in 1664.

David Teniers the Younger: The Boors’ Concert, early 1640s (DIA)

Michel Corrette: Les récréations du berger (Michèle Fromenteau, hurdy-gurdy; Françoise Cotte, harpsichord; Groupe des Instruments anciens de Paris; Roger Cotte, cond.)

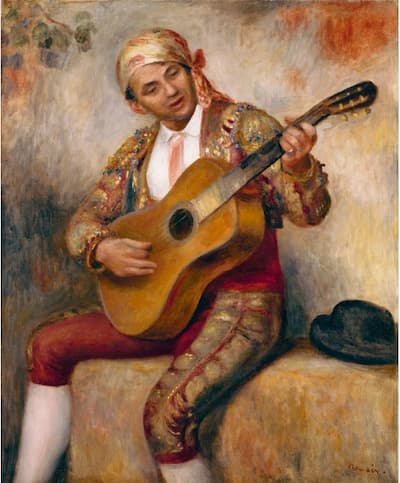

Although we’ve been looking primarily at art from the Netherlands, we can also find music in more modern works from France. In Renoir’s 1894 work, The Spanish Guitarist, we have a man in traditional Spanish dress and his guitar. France’s fascination with Spain occurred in more fields than in painting. A number of French composers also took journeys to the sunny south and made their own Spanish works, often evoking the country better than its native composers.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir: The Spanish Guitarist, 1894 (DIA)

Maurice Ravel: Rapsodie espagnole – IV. Feria (Lyon National Orchestra; Leonard Slatkin, cond.)

The Detroit collection has many more musical art gems than the ones selected here. We’ve seen music used to reinforce a social commentary on a number of levels – some through visuals and some through implied sound. The possession of an instrument can be a signal of high culture and the possession of the wrong instrument can be a signal of low culture – it all depends on the instrument, viola da gamba or bagpipes?

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Thanks for the very good article