Francis Poulenc

According to the apostle Luke, when the angels announced the birth of Christ to the Shepherds, they sang a hymn beginning with the words “Gloria in excelsis Deo” (Glory to God in the highest.) In time, additional verses were added to create the Greater Doxology — a Greek word meaning a hymn of praise to God that is frequently added to the end of canticles, psalms, and hymns. This Greater Doxology became part of morning prayers in the Byzantine rite, including Eastern Orthodox and Eastern Catholic Churches, in the 4th Century. By contrast, in the Roman Rite the hymn is not included in the Liturgy of the Hours, but sung or recited in the Mass. Over the centuries, more than two hundred plainchant melodies have been associated with this particular hymn.

Gregorian Chant: “Gloria”

As part of the Ordinary of the Mass, the text received numerous polyphonic musical settings. Among them is the Missa Ave Maris Stella (Hail Star of the Sea) by the Franco-Flemish composer Josquin des Prez (1450/55-1521), who was considered the greatest composer of his age. The Mass is based on a 9th-Century plainsong hymn praising the Virgin Mary, and Josquin greatly embellishes and elaborates the monophonic source material. This procedure known as paraphrase technique, was a popular means of mass composition from the late 15th century until the end of the 16th century. Because of Josquin’s immense popularity following his death, many publishers attributed anonymous work to him, and an editor sarcastically wrote, “Now that Josquin is dead, he is putting out more works than when he was alive.”

Josquin des Prez: Missa Ave maris stella, “Gloria”

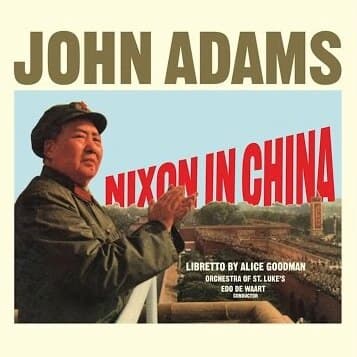

Antonio Vivaldi

The “Gloria” text, however, could also be used outside the liturgy of the Mass. This inspired several stand-alone musical setting, including two by Antonio Vivaldi (1675-1741), who served as the musical director of the Ospedale della Pietà (Hospital of Mercy) in Venice. An institution for orphaned or illegitimate girls, the “Ospedale” gradually gained international fame for the musical activities of its members. Luminaries and celebrities from all walks of society eagerly traveled to Venice to hear the girls perform in vocal and instrumental compositions. During his visit at the end of the 18th century, the English novelist, art critic and travel writer William Beckford wrote: “The sight of the orchestra makes me smile, because it is entirely of the feminine gender, and there is nothing more astonishing than to see a delicate white hand journeying across an enormous double bass, or a pair of roseate cheeks puffing, with all their efforts, at a French horn.”

Antonio Vivaldi: Gloria, RV 589

To commemorate the Peace of Dresden, which brought the Second Silesian War between Prussia and Austria to an end in 1745, Johann Sebastian Bach wrote a Church Cantata based on the “Gloria” text. First performed on Christmas Day 1745, it is his only Cantata work using Latin text. The music is an adaptation of three sections of a “Gloria” originally dating from 1733. In due course, Bach would use these sections — with slight alterations in scoring and instrumentation — in his monumental Mass in B minor.

Johann Sebastian Bach: Gloria in excelsis Deo, BWV 191

Josquin des Prez

Francis Poulenc (1899-1963) composed his setting of the “Gloria” on commission from the Koussevitsky Foundation in 1959. Scored for soprano solo, large orchestra, and chorus Poulenc divided the text into six sections. The work, which Poulenc described as “a large choral symphony,” is an odd mixture of lightheartedness and spirituality. It was premiered on 21 January 1961 in Boston, and Poulenc described the audience reaction to the second movement. “The ‘Laudamus Te’ caused a scandal; I wonder why? I was simply thinking, in writing it, of the Gozzoli frescoes in which the angels stick out their tongues; I was thinking also of the serious Benedictines whom I saw playing soccer one day.”

Francis Poulenc: Gloria FP 177

Please join me next time, when we look at various musical settings of the Nicene Creed — the profession of faith widely used in Christian liturgy.