Sephardic Romances: Traditional Jewish Music from Spain – Avrix mi galanica (Let Me in, My Love)

Ya viene el cativo (Now Comes the Prisoner)

With the invasion of the Moors in the 8th century, medieval Spain saw a blossoming of music, architecture and the arts, not only unparalleled in the rest of Europe at that time, but carrying well across the centuries into our own time.

Over the course of the next few months, we will be examining this close relationship, starting in the Middle Ages with the interplay and influence of Moorish, Christian and Jewish cultures in Al-Andalus, moving on to Spain’s ‘Golden Age’ in the 16th and the 17th centuries with the works of El Greco, Velazquez, Zurbaran, Cervantes and the music at the Court of Philip IV, and finally to the 19th and 20th centuries with Goya, Fernando Sor, Manuel de Falla, García Lorca, Gaudí and Picasso, amongst others.

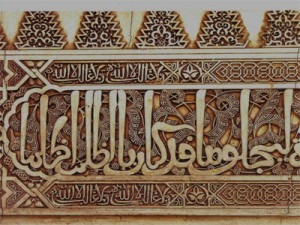

When Muslims invaded and conquered the Iberian Peninsula in 711 A.D., they brought with them their architecture, art and music, establishing new cities, including Cordoba, Seville, and Granada, centered around mosques surrounded by palaces, marketplaces, public baths, all built in the specific Moorish style. Since Islam forbids sacred iconography, i.e. figurative representation, it focuses instead on the cultivation of secular aspects of architecture, with calligraphy, floral and geometrical designs decorating mosques and palaces. Similar concepts can be found in music and poetry, where the sensual and the mundane are emphasized. These ‘romances’, singing the praises of beautiful women, would lead directly to the tradition of the troubadours (trouvères in France and Minnesänger in Germany), wandering minstrels courting women in the castles and courts of Europe.

During the 800 years of Moorish presence on the Iberian Peninsula, Muslim, Christian and Jewish inhabitants influenced and benefitted from each other. The most talented Christian artists (known as mozarabs) worked for their new rulers in the construction and decoration of mosques and palaces which reflected the Moors’ great love for nature and beauty, such as is seen in the gardens of the Alcázar in Seville: “With their flowers that seem to grow in a land of dream, and its birds from a magical sky” — the air suffused with the scent of jasmine and orange blossoms.

Many of the decorative elements found their way into Christian churches and Jewish synagogues, and elements of Moorish music infused the songs of Christians and Jews alike. Many Muslim craftsmen (Mudéjar) found themselves in Christian territory after the advancing re-conquest (‘Reconquista’). They now worked on churches and synagogues which were embellished with Moorish designs, such as the cathedral in Girona and the synagogue ‘El Transito’ in Toledo. Jewish physicians, philosophers, and lawyers (such as Maimonides and Avaroes) were distinguished members in Moorish society, closely connected to their Muslim counterparts. Christians, Muslims and Jews all inhabited the same spiritual universe, influencing, adapting and mutually enriching each community.

Moorish architecture has specific elements which not only carry on into the music of the time, but also became an inspiration to painters of Spain’s Golden Age and were taken up again in music, poetry and art of the 19th and 20th centuries.

From the outside, Moorish buildings seem simple, surrounded by high walls, unadorned, but once entered in circuitous fashion — there is no main façade, no central axis to which the buildings relate. Instead, buildings such as the Alcázar in Seville, and the magnificent Alhambra in Granada — slowly reveal themselves in all their beauty with their interior courtyards filled with flowers, flowing fountains and scented trees, similar to music, which develops slowly and is revealed and experienced in its performance.

The Alhambra’s ‘Patio de los Leones’ (The Patio of the Lions) which was donated by the Jewish community of Granada, inspired the following poems and songs:

“So close are the hard and the flowing/That you cannot tell which of the two is streaming/No, it is not water that streams towards those lions/It is a cloud of fluid movement”.

“Water runs into the basin of the fountain but it also runs out, like the lover who washes away her tears for fear of the sky. The architecture talks to whoever is looking at it, boasting its own beauty, characteristic of a finished and perfect work of art”.

The buildings are nothing but form, construction, decoration, geometry, harmony, splendor, grottoes of mother-of-pearl and wood, stucco and marble, domes of gold and enamel, dizzying splendor, until one discovers that there are letters hiding in the ornamentation and that the space describes itself through writing, as in the ‘tacas’ (niches) in the passage leading to the ‘Patio de Arrayanes’ (The Patio of Myrtles):

“I am the miḥrāb of prayer, I will go there and no further/You think that the pitcher of water murmurs its prayer from inside/Each time it is finished, it must start again”.

In fact, when we examine the construction of the Miḥrāb (prayer niche always pointing to Mecca), such as in the Mezquita, the great mosque of Cordoba, we notice an interesting fact. The niche is crowned by a horseshoe-shaped arch, enclosed by a rectangular frame, with its central point shifting up from below, i.e. de-centered. The entire arch seems to radiate; it is not rigid – it breathes as if expanding, while the rectangular frame encloses it, acting as counterbalance. The radiating energy and the absolute stillness form a perfect equilibrium, as is reflected in the fountains and water channels in the courtyards and gardens of the Alhambra — sound/music (fountains) and silence (water channels) — movement and stillness — the visible and invisible.

All of these elements also appear in the musical creations of the three cultures — in the Christian tradition of Alfons X El Sabio, “troubadour of the Virgin Mary”, with ‘saetas’ (chants sung by gypsies to the present day during ‘Semana Santa’, the Holy Week before Easter) and in Romances, Sephardic songs and jarchas — popular songs that appear in the final verses of the moaxajas (strophic poems), written both in Hebrew and Arabic. Many of the same musical instruments, such as lute, recorder, tambourine, bells, hurdy-gurdy and cymbals, are used in the respective compositions of the three cultures. Music, singing, and dancing were widespread both in high circles and among the general populace. It was here, in Al-Andalus that popular poetry as embodied in the zajal and muwashashaḥāt was sung everywhere and for every occasion — carrying on into the poetry of García Lorca and the music of the composers of the 19th and 20th centuries.

MUSIC LIST:

1. Tres culturas/ Three cultures – Jews, Christians and Muslims in Medieval Spain; Distribution Karonte, PNEUMA label, Madrid, e-mail: [email protected]

Tracks: # 1/2/6/11/13/18

2. Early Musik – Sephardic Romances – Naxos Label

Tracks: # 1 and 16

3. Poemas de la Alambra [poems by Ibn Zamrak (1333-1393), appearing as writing decoration in the walls of the palaces]; production Eduardo Paniagua, PNEUMA label;

Tracks: # 6 and 1

4. Devotion – Music and Chants from the Great Religions, The New Earth Records, The Living Tradition;

Tracks: #1, 9 and 10

5. Cantes des Pueblo, ARC Music Label;

Tracks: # 1 (Ronda a la Virgen), 10 and 11

Ki Eshmera Shabbat

Cantiga de Santa Maria

Poemas de La Alhambra