A recent exhibition of major works by the Pre-Raphaelite painters at the National Gallery in Washington, D.C. brings into focus the close relationship between painting, poetry and music which existed throughout much of the 19th century.

A recent exhibition of major works by the Pre-Raphaelite painters at the National Gallery in Washington, D.C. brings into focus the close relationship between painting, poetry and music which existed throughout much of the 19th century.

19th century Britain saw a rebirth of British music and art, passionately supported not only by Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, but also by the rising new middle-class industrialists and wealthy manufacturers. The Great Exhibition of 1851 had focused on significant industrial British inventions, British goods and British commerce throughout the world. 1871 saw the opening of the now famous Royal Albert Hall, built to commemorate Queen Victoria’s late Consort, as well as the first performance of a Gilbert and Sullivan operetta. In 1888, Thomas Edison first demonstrated his recording phonograph to the British public at the Crystal Palace which, in the ensuing years, would make recordings available to a larger audience. In 1895, the first ‘Proms’ concert was given under the direction of the young Henry Wood in the Queen’s Hall, starting the yearly tradition of summer concerts, which eventually were moved to the Royal Albert Hall, and are still popular to this day. Henry Wood introduced music of the classical and romantic period to the general public, which until then they had been unable to afford to attend. Also, during the 19th century, many European composers, such as Mendelssohn, Grieg, Fauré, as well as many Russians, came to England to conduct and introduce a new romantic style of classical music to the British public. In turn, they fostered a new generation of British composers, such as Holst, Parry, Delius and Elgar, who were writing music inspired by romance, nature, Shakespeare’s plays, fairy tales and the gods and heroes of classical Greek and Roman mythology, touching on similar topics which had become the subjects of Wagner’s and Verdi’s operas (please see my March and April Interlude articles).

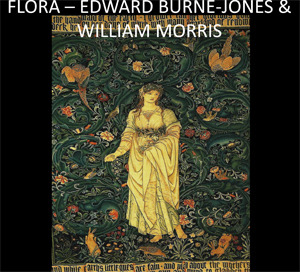

In 1848, a young group of painters set out to reform English painting, calling themselves the “Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood”. Just as the Impressionist painters had opposed the constraints of the ‘Académie des Beaux Arts’ in Paris, these young British painters also rejected the demands of the ‘Royal Academy’ in London to adhere to the principles of the Italian Renaissance masters, and Raphael in particular. The Brotherhood rejected all of the established Renaissance conventions and favored a return to the ‘imagined’ purity of medieval art, and a painting style which closely observed nature, capturing its every facet, using bright colors and most importantly, paintings that would tell a story. The initial group included Walter Howell Deverell (1827-1854), John Everett Millais (1829-1896), William Holman Hunt (1827-1910) and Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882), who enjoyed a close relationship, working together on painting excursions and visiting each other’s studios. They were later joined by Burne-Jones (1833-1898) and William Morris (1834-1896). The latter part of the 19th century saw an evolution of the Brotherhood, particularly under the influence of William Morris, with fine arts now joining with the Arts and Crafts Movement, extending into the production of tapestries, furniture and stained glass windows, all of which expressed similar ideas.

In 1848, a young group of painters set out to reform English painting, calling themselves the “Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood”. Just as the Impressionist painters had opposed the constraints of the ‘Académie des Beaux Arts’ in Paris, these young British painters also rejected the demands of the ‘Royal Academy’ in London to adhere to the principles of the Italian Renaissance masters, and Raphael in particular. The Brotherhood rejected all of the established Renaissance conventions and favored a return to the ‘imagined’ purity of medieval art, and a painting style which closely observed nature, capturing its every facet, using bright colors and most importantly, paintings that would tell a story. The initial group included Walter Howell Deverell (1827-1854), John Everett Millais (1829-1896), William Holman Hunt (1827-1910) and Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882), who enjoyed a close relationship, working together on painting excursions and visiting each other’s studios. They were later joined by Burne-Jones (1833-1898) and William Morris (1834-1896). The latter part of the 19th century saw an evolution of the Brotherhood, particularly under the influence of William Morris, with fine arts now joining with the Arts and Crafts Movement, extending into the production of tapestries, furniture and stained glass windows, all of which expressed similar ideas.

E.Grieg

Peer Gynt Suite No. 1, Op. 46

Morgenstemning (Morning Mood)

Millais, Hunt and Rossetti began as fellow students at the Royal Academy Schools. Frustrated with the Schools’ traditional training and the constant emphasis on 16th century painting, they began formulating radical ideas, linking painting and poetry, taking subject matter from the Bible, the works of Shakespeare, as well as the poetry of John Keats (1795-1821). Millais’s painting ‘Isabella’ is based on a poem by Keats of the same name. We have to remember that public interest in the Middle Ages culminated in 19th century England — Gothic design was chosen for the New Houses of Parliament to replace the earlier buildings gutted by fire in 1833, and furniture, tapestries, and stained glass windows all took their inspiration from the Middle Ages. Prince Albert also favored the Northern European Gothic design, and collectors focused on the works of early Dutch and German Pre-Renaissance masters.

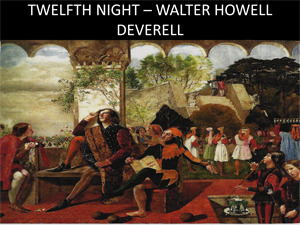

The young painters were supported and publicized by the art critic John Ruskin, in particular through his work ‘Modern Painters’ (first published in 1843), in which he proclaimed that the young artists should “go to Nature in all singleness of heart …rejecting nothing, selecting nothing and scorning nothing”. All of the Pre-Raphaelite painters took his pronouncements literally – their painting excursions took them into the English countryside, which became the backdrop for their biblical and theatrical subject matter. In ‘Twelfth Night’, Deverell shows us Act II of Shakespeare’s play of the same title, when Duke Orsino (in the center) requests that his clown Feste sing the song “Come away, come away, Death” — looked upon adoringly by Viola, disguised as a page. Musicians and dancers — all in meticulously researched costumes and accessories — fill the canvas. The painting is heavy on symbolism — the rose between Viola and Orisino is a symbol of love as are the passion flowers in the background between them, and the honeysuckle behind Orsino is a symbol of devotion. The setting also suggests the close relationship which all of the arts enjoyed in Medieval times.

The young painters were supported and publicized by the art critic John Ruskin, in particular through his work ‘Modern Painters’ (first published in 1843), in which he proclaimed that the young artists should “go to Nature in all singleness of heart …rejecting nothing, selecting nothing and scorning nothing”. All of the Pre-Raphaelite painters took his pronouncements literally – their painting excursions took them into the English countryside, which became the backdrop for their biblical and theatrical subject matter. In ‘Twelfth Night’, Deverell shows us Act II of Shakespeare’s play of the same title, when Duke Orsino (in the center) requests that his clown Feste sing the song “Come away, come away, Death” — looked upon adoringly by Viola, disguised as a page. Musicians and dancers — all in meticulously researched costumes and accessories — fill the canvas. The painting is heavy on symbolism — the rose between Viola and Orisino is a symbol of love as are the passion flowers in the background between them, and the honeysuckle behind Orsino is a symbol of devotion. The setting also suggests the close relationship which all of the arts enjoyed in Medieval times.

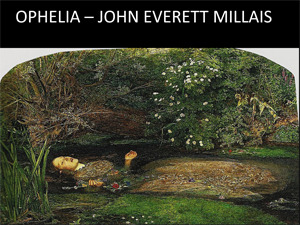

Millais’ painting of ‘Ophelia’ (from Shakespeare’s ‘Hamlet’) depicts her watery death surrounded by flowers, which again carry a heavy symbolism (the symbolism of plants and flowers was much in use and very important in the Middle Ages) — the willow, nettle and daisies are representative of love, pain and innocence; the pansies on her dress symbolize ‘thought and love in vain’ and the red poppy was given to her by Hamlet, predicting that her journey would end in death. Millais’s ‘truth to nature’ found him capturing the natural details near the Hogsmill River at Malden in Surrey, often in severe weather, despairing when swans destroyed the water-weeds he was attempting to capture on canvas. His model for Ophelia, Elisabeth Sidall, had to float for hours in a bathtub so that he could capture the floating Ophelia in her soggy dress — until she caught a cold. She never modeled for Millais again.

A Village Romeo and Juliet: The Walk to the Paradise Garden

A Village Romeo and Juliet: The Walk to the Paradise Garden

Musically, Felix Mendelssohn’s ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’, Edvard Grieg’s ‘Morning’ from ‘Peer Gynt’ and Frederick Delius’ ‘Summer Evening’ or ‘The Walk to the Paradise Garden’ (featured in his composition ‘A Village Romeo and Juliet’) connect to the works of the Pre-Raphaelites not just by their subject matter, drawing inspiration from the works of Shakespeare and Ibsen, but conjuring images of nature, beautiful scenery and countryside — from a morning in a lovely garden filled with flowers as the sun rises in the sky to a summer evening. In ‘The Walk to the Paradise Garden’, Delius’ wonderful orchestration and impassioned melodies depict the scene of lovers finding freedom in a natural paradise.

Massenet

Thais

Act II Scene 2: Meditation

Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s painting was probably inspired by a play performed in London in 1856/57 depicting the tragic story of Pia de’ Tolomei, encountered by Dante in his journey through Purgatory. The frame of the painting is inscribed with verses and Rossetti’s translations from the 5th canto of Dante’s Purgatorio, emphasizing and explaining the meaning of the painting, important elements in the works of the Pre-Raphaelites. In the canto, Dante meets La Pia, who had been imprisoned by her husband in a Gothic-style fortress. All of the elements in the painting are symbolic: the sadness in her face, withdrawn from the world, unaware of her surroundings; the ivy surrounding her — a symbol of constancy as she fingers her wedding ring; the black and silver rosary on the bible refers to her religious belief and to her name, i.e. the Pious; the sundial represents the passage of time and the ravens in the sky are messengers of impending death — references to Medieval belief. Musically, we can link the painting to Massenet’s opera ‘Thais’ (written in 1894), and in particular to the beautiful, ethereal violin melody, ‘Méditation’, which represents Thais’ conversion to a holier life.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s painting was probably inspired by a play performed in London in 1856/57 depicting the tragic story of Pia de’ Tolomei, encountered by Dante in his journey through Purgatory. The frame of the painting is inscribed with verses and Rossetti’s translations from the 5th canto of Dante’s Purgatorio, emphasizing and explaining the meaning of the painting, important elements in the works of the Pre-Raphaelites. In the canto, Dante meets La Pia, who had been imprisoned by her husband in a Gothic-style fortress. All of the elements in the painting are symbolic: the sadness in her face, withdrawn from the world, unaware of her surroundings; the ivy surrounding her — a symbol of constancy as she fingers her wedding ring; the black and silver rosary on the bible refers to her religious belief and to her name, i.e. the Pious; the sundial represents the passage of time and the ravens in the sky are messengers of impending death — references to Medieval belief. Musically, we can link the painting to Massenet’s opera ‘Thais’ (written in 1894), and in particular to the beautiful, ethereal violin melody, ‘Méditation’, which represents Thais’ conversion to a holier life.

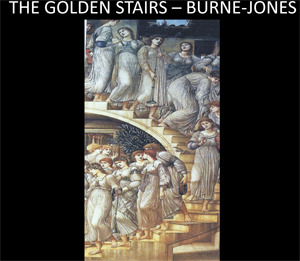

Edward Burne-Jones’ painting depicts eighteen classically dressed women (fashioned after the Elgin Marbles which he had sketched at the British Museum), descending a staircase holding various unusual musical instruments, some engaged in conversations, others seeming to be lost in thought, enclosed in an interior space with only the doves at the window hinting at the world beyond. A dreamlike, hushed atmosphere is created by the almost ethereal coloring throughout the painting, which the critic Frederic George Stephens likened to the palette of the early Renaissance artist Piero della Francesca, whom Burne-Jones profoundly admired. However, the painting does not convey a specific subject matter (for which Burne-Jones was severely criticized), but therefore does relate to music, as music sets the mood and leaves all interpretation open in the mind of the listener.

With the end of the Victorian age, the Pre-Raphaelite experiment in painting came to a close, and we see a different aesthetic — the Aesthetic and Symbolist movement — emerge, for which “all art constantly aspired towards the condition of music” — just as Burne-Jones’ painting of The Golden Stairs, which “…. like music could function in a purely abstract and evocative way” (William Pater cited in Pre-Raphaelites, Heather Birchall p. 84).

More Arts

- Alexandre Dumas (1802-1870)

“Music is the only noise for which one is obliged to pay” We look at his collaborations with composers on operas and more! - “In the Hall of the Mountain King”

Henrik Ibsen in Music "Peer Gynt goes very slowly. It is a horribly intractable subject except for a few places… " - Edgar Degas (1834-1917)

“No art could be less spontaneous than mine” Look at Degas' burning passion for opera from his artwork - Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669)

Born on 15 July Learn about his ancestry, childhood and more