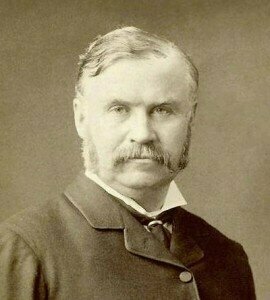

W.S. Gilbert

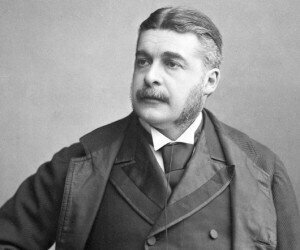

Gilbert, a writer of humorous verse, stories and plays, met Sullivan, a young composer, and they started working together in 1871. Their first comic opera was Thespis, a mixture of political satire and French grand opera stylings. It had a great run on stage but the score was never published and is now lost.

Their next co-production was Trial by Jury (1875), a spoof on a breach of promise marriage suit. This was the first opera in which they established a character and style that would appear in all their operas: the minor character (baritone) who sang a song with impossibly fast lyrics (the ‘patter’ song). In Trial by Jury, it’s the judge’s song ‘When I, good friends…’.

Sullivan: Trial by Jury: Song: When I, good friends … (Donald Maxwell, Learned Judge; Chamber Choir of the Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama; BBC Nation Orchestra of Wales; Richard Hickox, cond.)

Arthur Sullivan

Gilbert, who had an established reputation for his humorous poems, was also known for his parodies of popular works of the day – his Dulcamara, or the Little Duck and the Great Quack was a parody of Donizetti’s L’elisir d’amore. Robert the Devil was a parody of Meyerbeer’s Robert le diable, and so on. After he was an established playwright, he also became a director. Theatre, by the mid-to-late 19th century was a debased art with a bad reputation. As a director, he ran disciplined rehearsals so that he could create a unified world in his productions: everything for a natural and clear performance. This discipline and clarity were the backbone of G&S comic operas. He also replaced the star system with that of a unified ensemble – as could be seen in the selection from Penzanze above.

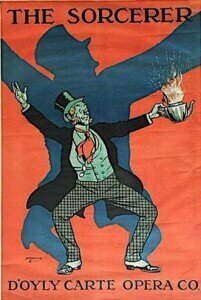

G&S’s next collaboration was The Sorcerer (1877), a minor hit.

The Sorcerer

Sullivan: H.M.S. Pinafore: Act I: Recitative: Hail Men-o’-war’s men; song: I’m Called Little Buttercup (Hilary Summers, Buttercup; Scottish Opera Orchestra; Richard Egarr, cond.)

The money that the producer, Richard D’Oyly Carte, made from Pinafore meant that he could split with his partners and, together with G&S, create the D’Oyley Carte Opera Company, which became the established company for all G&S operas onward.