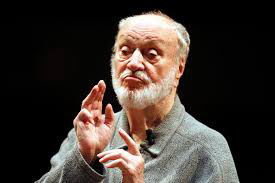

Kurt Masur had a comparatively simple philosophy on music and musical performances. “Conductors,” he once wrote, “should only conduct those pieces where they feel they have something special to say; then people will accept it.” Although Masur has not shied away from tackling works by contemporary composers, his reputation and legacy largely rests on insightful interpretations and recordings of a core central-European repertory, with a special emphasis on Beethoven. And that insight was clearly shaped during his 20-year tenure with the Gewandhausorchester in Leipzig. Felix Mendelssohn founded that institution almost 150 years ago with the premise that members of the orchestra are teaching and gradually bringing their students into the orchestra. A firm believer in this type of musical apprenticeship, Masur saw it as a way of passing a characteristic and authentic sound from one generation to the next. For Masur, the basic sound of a Schumann, Brahms or Beethoven symphony, which does require a special string technique, has not really changed over time. Clearly, interpretations change depending on conductor and the soundscape varies from orchestra to orchestra, “but the sound essence is very similar.”

Kurt Masur had a comparatively simple philosophy on music and musical performances. “Conductors,” he once wrote, “should only conduct those pieces where they feel they have something special to say; then people will accept it.” Although Masur has not shied away from tackling works by contemporary composers, his reputation and legacy largely rests on insightful interpretations and recordings of a core central-European repertory, with a special emphasis on Beethoven. And that insight was clearly shaped during his 20-year tenure with the Gewandhausorchester in Leipzig. Felix Mendelssohn founded that institution almost 150 years ago with the premise that members of the orchestra are teaching and gradually bringing their students into the orchestra. A firm believer in this type of musical apprenticeship, Masur saw it as a way of passing a characteristic and authentic sound from one generation to the next. For Masur, the basic sound of a Schumann, Brahms or Beethoven symphony, which does require a special string technique, has not really changed over time. Clearly, interpretations change depending on conductor and the soundscape varies from orchestra to orchestra, “but the sound essence is very similar.”

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 6 “Pastoral” (Leipzig Gewandhaus/Kurt Masur)

This emphasis on maintaining a tradition of sound, and Masur’s focus on a relatively narrow band of masterworks has not been universally welcomed. New York critics were quick to suggest that Masur “has never shown much ability to project Beethoven’s fire and passion, and contents himself with a certain comfortable generalized musicality.” In this time of excessively fast tempos and lightweight performing styles—commonly referred to as the “microwaveable style of musical performance”—Masur’s interpretations have always gone against the popular grain. Masur habitually rejected the more forceful demands from the recording industry and steadfastly projected his philosophy of Beethoven’s symphonic output. For him, Beethoven’s symphonies were musical statements that transcended the mundane aspects of the human condition. Of course Beethoven passed gas in inappropriate situations, was terribly self-conscious about the pockmarks in his face and got dead drunk at the spur of a moment, yet in his music he was able to leave these earthy matters far behind. Above all, according to Masur, “Beethoven produced sounding documents that are universally understood. They are clearly understood in different ways around the world, but like an intricate and complex cake anybody can find a slice that is beautiful and somehow impressive.” Whether one likes or dislikes Masur’s interpretations clearly depends on what we as listeners bring to the table. Be that as it may, with Kurt Masur we have lost a tangible connection to the past; a connection that always ensured that commitment and devotion stood in the service of his undying belief “in the power of music to bring humanity closer together.” I can’t think of anything more fitting to demonstrate this humility than his beautiful recording of Beethoven’s “Pastoral” Symphony. Together with the Gewandhaus, Masur achieved a sense of serenity—stormy episodes none withstanding—to turn a black and white musical score into a living and colorful breathing entity.

Beethoven Symphony No. 9 – Finale

Gewandhausorchester Leipzig

Kurt Masur

More Blogs

-

The Greatest Musician Portraits by John Singer Sargent When a master painter captured musical genius!

The Greatest Musician Portraits by John Singer Sargent When a master painter captured musical genius! -

The Sounds of Summer From Barber's Knoxville to Sousa's marches—summer in music!

The Sounds of Summer From Barber's Knoxville to Sousa's marches—summer in music! -

What Happened to Sibelius’s Six Daughters? When practicing piano wasn't allowed in a composer's house!

What Happened to Sibelius’s Six Daughters? When practicing piano wasn't allowed in a composer's house! - Pixie Party Time

International Fairy Day Delight Enchanting music from Mendelssohn to Stravinsky