Nicholas I, Prince Eszterháza was crazy about the arts! He built a number of palaces and his taste for opera and other grand musical productions earned him the title “the Magnificent.” He certainly was extravagant in his clothing budget, and famously wore a jacket studded with diamonds. Beyond the bling, he was intensely musical and played the cello, the viola da gamba, and the now obscure baryton. And of course, he is remembered as the principal employer of Joseph Haydn. He maintained his own orchestra and staged numerous operatic productions, which eventually became the focus of the entire musical establishment. Not to be outdone, he had a feverish passion for collecting. His private museum housed valuable books, paintings, sculptures, antiquities from around the world, exotic stones and woods, and a huge collection of roughly 400 clocks! The principles of the mechanical clock as we know it today had only recently been invented, and the 18th century magnificently exploited the object as art.

Nicholas I, Prince Eszterháza was crazy about the arts! He built a number of palaces and his taste for opera and other grand musical productions earned him the title “the Magnificent.” He certainly was extravagant in his clothing budget, and famously wore a jacket studded with diamonds. Beyond the bling, he was intensely musical and played the cello, the viola da gamba, and the now obscure baryton. And of course, he is remembered as the principal employer of Joseph Haydn. He maintained his own orchestra and staged numerous operatic productions, which eventually became the focus of the entire musical establishment. Not to be outdone, he had a feverish passion for collecting. His private museum housed valuable books, paintings, sculptures, antiquities from around the world, exotic stones and woods, and a huge collection of roughly 400 clocks! The principles of the mechanical clock as we know it today had only recently been invented, and the 18th century magnificently exploited the object as art.

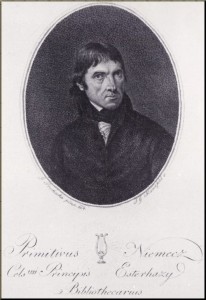

Until his sudden death in 1779, the Royal Librarian Philipp Georg Bader, who also wrote a number of librettos for marionette operas, had been in charge of Nicholas’ collection. The monk Joseph Primitivus Niemecz, who functioned as librarian, chaplain, cellist and clockmaker, replaced him. Father Niemecz had written a well-known history of the Eszterháza family, and was a highly skilled player on the keyboard, harp, cello, violin, viola da gamba and baryton. Yet his real genius lay in mechanical matters, particularly clocks and mechanical musical instruments. In the event, Haydn and Niemecz became friends and Niemecz played the continuo cello parts at all the opera performances, sitting right next to Haydn who played the continuo. At the same time, Niemecz was working on his mechanical clockwork machines, producing pocket watches and a “clockwork tableau with the naked figures of Adam and Eve combined with fountains and other waterworks.” He even produced a musical chair, which played a tune when a person sat down on it, and a musical spinning wheel. Unsurprisingly, Niemecz commissioned Haydn to compose pieces for his mechanical clockwork organ!

Until his sudden death in 1779, the Royal Librarian Philipp Georg Bader, who also wrote a number of librettos for marionette operas, had been in charge of Nicholas’ collection. The monk Joseph Primitivus Niemecz, who functioned as librarian, chaplain, cellist and clockmaker, replaced him. Father Niemecz had written a well-known history of the Eszterháza family, and was a highly skilled player on the keyboard, harp, cello, violin, viola da gamba and baryton. Yet his real genius lay in mechanical matters, particularly clocks and mechanical musical instruments. In the event, Haydn and Niemecz became friends and Niemecz played the continuo cello parts at all the opera performances, sitting right next to Haydn who played the continuo. At the same time, Niemecz was working on his mechanical clockwork machines, producing pocket watches and a “clockwork tableau with the naked figures of Adam and Eve combined with fountains and other waterworks.” He even produced a musical chair, which played a tune when a person sat down on it, and a musical spinning wheel. Unsurprisingly, Niemecz commissioned Haydn to compose pieces for his mechanical clockwork organ!

Haydn/Niemecz “Flötenuhr”

In all, there seem to have been a number of specific collaborations between Haydn and Niemecz. And four of these “Flötenuhr” instruments are still extant, one dating from 1789 and the others originating from the early 1790s, respectively. Together, these four instruments play 40 tunes, 10 of which are shared between them. The cylinder of these organ clocks was programmed with customary pins and with bridges of varying lengths. “The pins take care of the short notes, and the bridges represent the range of longer notes, and the instruments are capable of producing tunes of extended musical complexity and finesse.” The only major restriction is the playing length of the music, and the Haydn/Niemecz instruments belong to the “one-turn-one-melody type.” After each revolution, the cylinder makes a lateral shift, and a new piece of music can be played. The sound is produced via roughly 25 stopped wooden pipes attached to a mechanical bellow.

In all, there seem to have been a number of specific collaborations between Haydn and Niemecz. And four of these “Flötenuhr” instruments are still extant, one dating from 1789 and the others originating from the early 1790s, respectively. Together, these four instruments play 40 tunes, 10 of which are shared between them. The cylinder of these organ clocks was programmed with customary pins and with bridges of varying lengths. “The pins take care of the short notes, and the bridges represent the range of longer notes, and the instruments are capable of producing tunes of extended musical complexity and finesse.” The only major restriction is the playing length of the music, and the Haydn/Niemecz instruments belong to the “one-turn-one-melody type.” After each revolution, the cylinder makes a lateral shift, and a new piece of music can be played. The sound is produced via roughly 25 stopped wooden pipes attached to a mechanical bellow.

Franz Joseph Haydn: Pieces for Musical Clock, Hob. XIX, excerpts

In 1793, Haydn and Niemecz had presented Prince Nicolas II of Esterházy with an elaborate musical clock. The new Prince had no interest in Music and released Haydn onto the international stage. Haydn had composed 12 short pieces for the Niemecz instrument, and with his second visit to London coming up shortly, he decided to reuse a short ostinato accompaniment in the second movement of a symphony. If you are a friend of Haydn’s music, you already know where this story takes us. And you are right, because the Haydn Symphony No. 101, the ninth of his London Symphonies, is known as “The Clock” because of the ticking rhythm throughout the second movement. The response of the audience was extremely enthusiastic, and the Morning Chronicle wrote, “As usual the most delicious part of the entertainment was a new grand Overture (Symphony) by HAYDN; the inexhaustible, the wonderful, the sublime HAYDN! The first two movements were encored; and the character that pervaded the whole composition was heartfelt joy. Every new symphony he writes, we fear, till it is heard, he can only repeat himself; and we are every time mistaken.” And a 20th century music critic wrote, “Haydn has a gratifying number of different clocks in his shop, offering ‘tick-tock’ in a happy variety of colors.”

In 1793, Haydn and Niemecz had presented Prince Nicolas II of Esterházy with an elaborate musical clock. The new Prince had no interest in Music and released Haydn onto the international stage. Haydn had composed 12 short pieces for the Niemecz instrument, and with his second visit to London coming up shortly, he decided to reuse a short ostinato accompaniment in the second movement of a symphony. If you are a friend of Haydn’s music, you already know where this story takes us. And you are right, because the Haydn Symphony No. 101, the ninth of his London Symphonies, is known as “The Clock” because of the ticking rhythm throughout the second movement. The response of the audience was extremely enthusiastic, and the Morning Chronicle wrote, “As usual the most delicious part of the entertainment was a new grand Overture (Symphony) by HAYDN; the inexhaustible, the wonderful, the sublime HAYDN! The first two movements were encored; and the character that pervaded the whole composition was heartfelt joy. Every new symphony he writes, we fear, till it is heard, he can only repeat himself; and we are every time mistaken.” And a 20th century music critic wrote, “Haydn has a gratifying number of different clocks in his shop, offering ‘tick-tock’ in a happy variety of colors.”

Franz Joseph Haydn: Symphony No. 101, “The Clock,” Andante