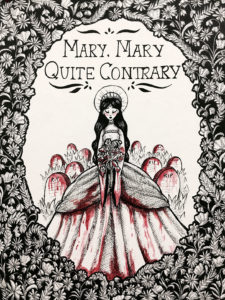

A good many nursery rhymes have acquired various historical explanations. Although it is much debated whether such explanations are grounded in fact or simply a matter of urban lore, it is clear that these innocent sounding rhymes support multiple levels of meaning. The popular English nursery rhyme “Mary, Mary, Quite Contrary” has acquired a number of religious and historical interpretations, even though its origins and meanings are disputed.

A good many nursery rhymes have acquired various historical explanations. Although it is much debated whether such explanations are grounded in fact or simply a matter of urban lore, it is clear that these innocent sounding rhymes support multiple levels of meaning. The popular English nursery rhyme “Mary, Mary, Quite Contrary” has acquired a number of religious and historical interpretations, even though its origins and meanings are disputed.

Mary, Mary, quite contrary,

How does your garden grow?

With silver bells, and cockle shells,

And pretty maids all in a row.

Little Miss Muffet

The character of Mary has been most often ascribed to “Bloody Mary” or Mary Tudor, first daughter of Henry VIII, who later became Queen Mary I of England. A Catholic zealot, she summarily executed Protestants and her garden is supposed to refer to the ever-growing graveyard of Protestant martyrs. Silver bells and cockle shells allude to instruments of torture, and the pretty maids all in a row are not household helpers but refer to guillotines nicknamed “the maidens.”

Archy Rosenthal: 6 Variations and Fugue on an old Nursery Rhyme “Mary Mary, Quite Contrary”

Not all nursery rhymes are connected with blood and gore, although there might still be a historical connection. “Little Miss Muffet” first appeared in print in 1805 in a publication titled Songs for the Nursery.

Little Miss Muffet

Sat on a tuffet,

Eating her curds and whey;

There came a great spider,

Who sat down beside her,

And frightened Miss Muffet away.

Jack and Gill, year 1791

It has been suggested that the rhyme is connected to Dr. Thomas Muffet, a 16th-century English physician and entomologist. And little “Miss Muffet” identifies his squeamish stepdaughter Patience. Believe it or not, but several novels and films, including Along Came a Spider have taken inspiration from that particular rhyme.

Constance Walton: 4 Little Songs, “Litte Miss Muffet”

The traditional English nursery rhyme “Jack and Jill” was first published in 1765. Predictably, a number of different verses have come into use, but the most common first verse reads:

Jack and Jill

Went up the hill

To fetch a pail of water

Jack fell down

And broke his crown,

And Jill came tumbling after.

Ring around the Rosie

The melody commonly associated with that rhyme dates from 1870, and various theories have been advanced to explain the meaning. I like the one that posits the attempt by King Charles I to reform the taxes on liquid measures. He ordered that the volume of a Jack (1/8 pint) be reduced, but that the tax remained the same. Thus, Jack fell down below the crown marker on many pint glasses, and Jill, or actually a “gill,” or ¼ pint dropped in volume a consequence. Believe it or not, but the woodcut that accompanied the first recorded version of the rhyme showed tow boys and used the spelling “Jack and Gill.”

If you tell folkorists and cultural crusaders that the well-known nursery rhyme “Ring around the Rosie” is possibly connected to the Great Plague of London that killed roughly 100,000 people during the 1600s, you’ll likely get into a mighty argument.

Ring-a-ring o’ roses,

A pocket full of posies,

A-tishoo! A-tishoo!

We all fall down.

To be sure, many different version of the rhyme are known around Europe, a number of them connected or adapted to local customs, words, and games. The Plague theory became popular in the 19th century, while the 21st century maintains that the rhyme means absolutely nothing. Just a bit too sterile, don’t you think?

We can not hear the musical examples

Please click on the music titles.