Sarah Chang

The life of a child star in any field is not easy. You’re inside working while all your contemporaries are playing or sleeping or just having fun together. With so many children performers, however, there’s often a story behind it, of an inspirational performance they heard, or a relative who encouraged their work. They are seized with a passion and their parents are often the ones who can help them push to achieve.

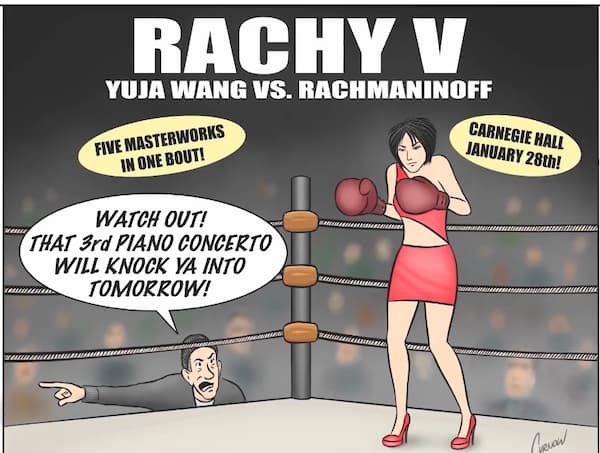

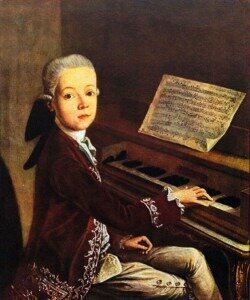

We can all name some child prodigies, starting with pianist Mozart at age 4, violinist Sarah Chang who started performing at age 5 and issued her first studio album at age 9, cellist YoYo Ma who started performing at age 5, pianist Lang Lang who entered the Beijing Conservatory at age 8, composer/pianist Georges Bizet who entered the Paris Conservatory at age 9, or Edgard Varèse who composed his first opera at age 12. This is a random list, extending from the 18th to the 21st century and is just a hint at the wide variety of precocious children in music.

Mozart, Symphony No. 1 in E-Flat Major, K. 16: I. Allegro molto (Danish National Chamber Orchestra ,Adam Fischer, cond. )

Yo-Yo Ma at age 7 (1962); at 30 (1985); at age 16 (1971)

The Young Mozart

It’s rare that the musical child is interested only in music: often their musical abilities are sparked by interesting ideas in science or language, and so their musical training is indicative of their potential in a number of fields.

Lang Lang before he took up the piano

It’s interesting to note that most child prodigies develop in fields that have very strict rules: music, chess, or math, but rarely in fields that require a depth of knowledge and practice. You never see child prodigies in engineering or chemistry, for example.

So let’s appreciate the prodigies we meet, and stop anticipating what they’ll do next in music: it may not be all that straightforward.