The dumplings

When Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) took up his conducting appointment in the city of Olmütz, located in the Moravian region of the Czech lands, everybody thought he was a rather odd duck. According to contemporary reports, “At the inn where the singers met in the evening, he invited ridicule by drinking water instead of wine or beer. Refusing meat, he asked for spinach and apples, and loudly declared his allegiance to Richard Wagner’s vegetarian principles, throwing in a plea for woolen underwear for good measure. The citizens of this little town were agreed that he was a very queer specimen. Mahler spurned the food they offered him, and went hungry for the sake of his convictions.” Mahler’s convictions were based on an article Richard Wagner published in the Bayreuther Blätter in 1880. Wagner essentially followed the writings of Arthur Schopenhauer, who famously stated, “The assumption that animals are without rights and the illusion that our treatment of them has no moral significance is a positively outrageous example of Western crudity and barbarity. Universal compassion is the only guarantee of morality.”

In Wagner’s article, essentially an endorsement of vegetarianism, he writes, “When first it dawned on human wisdom that the same thing breathed in animals as in mankind, it appeared too late to avert the curse which, ranging ourselves with the beasts of prey, we seemed to have called down upon us through the taste of animal food: disease and misery of every kind, to which we did not see mere vegetable-eating men exposed. The insight thus obtained led further to the consciousness of a deep-seated guilt in our earthly being: it moved those fully seized therewith to turn aside from all that stirs the passions, through free-willed poverty and total abstinence from animal food.” Wagner never became a total vegetarian, and neither did Mahler, although he tried. “For the last month,” he writes to a friend, “I have been a strict vegetarian. The moral effects of this regime are immense, owing to the voluntary subjugation of the flesh and the resulting absence of desires. You will appreciate how full I am of this idea when I tell you that I expect it to work the regeneration of mankind. I advise you to change over to a natural way of life, with proper nourishment (whole-meal bread), and you will soon feel the benefit.” One could certainly call the third movement of Mahler’s 1st Symphony a musical endorsement of vegetarianism. Titled “Feierlich und gemessen” (Solemnly and measured), it unfolds as a funeral march based on the popular tune “Bruder Martin” (Frère Jacques). Conceptually, it is based on E.T.A. Hoffmann’s Fantasiestücke (Fantasy pieces) and the ensuing woodcut by Moritz von Schwind, in which the corpse of a hunter is carried to its grave by a procession of animals. It is highly doubtful that Mahler would ever have harmed an animal or human, but he certainly would have killed for the Marillenknödel (apricot dumplings) of his sister Justine. Here then is the original recipe, discovered by musicologist Ira Braus.

In Wagner’s article, essentially an endorsement of vegetarianism, he writes, “When first it dawned on human wisdom that the same thing breathed in animals as in mankind, it appeared too late to avert the curse which, ranging ourselves with the beasts of prey, we seemed to have called down upon us through the taste of animal food: disease and misery of every kind, to which we did not see mere vegetable-eating men exposed. The insight thus obtained led further to the consciousness of a deep-seated guilt in our earthly being: it moved those fully seized therewith to turn aside from all that stirs the passions, through free-willed poverty and total abstinence from animal food.” Wagner never became a total vegetarian, and neither did Mahler, although he tried. “For the last month,” he writes to a friend, “I have been a strict vegetarian. The moral effects of this regime are immense, owing to the voluntary subjugation of the flesh and the resulting absence of desires. You will appreciate how full I am of this idea when I tell you that I expect it to work the regeneration of mankind. I advise you to change over to a natural way of life, with proper nourishment (whole-meal bread), and you will soon feel the benefit.” One could certainly call the third movement of Mahler’s 1st Symphony a musical endorsement of vegetarianism. Titled “Feierlich und gemessen” (Solemnly and measured), it unfolds as a funeral march based on the popular tune “Bruder Martin” (Frère Jacques). Conceptually, it is based on E.T.A. Hoffmann’s Fantasiestücke (Fantasy pieces) and the ensuing woodcut by Moritz von Schwind, in which the corpse of a hunter is carried to its grave by a procession of animals. It is highly doubtful that Mahler would ever have harmed an animal or human, but he certainly would have killed for the Marillenknödel (apricot dumplings) of his sister Justine. Here then is the original recipe, discovered by musicologist Ira Braus.

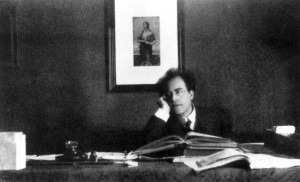

Gustav Mahler

Ingredients:

2.2 lbs. potatoes

8.75 oz. flour

One egg

Pinch of salt

3.15 oz. butter

3.5 oz. bread crumbs

13 oz. apricots

Preparation: Place the potatoes, cut and peeled, through a mill once, then work them into the flour, egg and salt on a cutting board while they are still warm to make a smooth paste.

With a rolling pin, or by hand, knead the paste, flatten it and cut into fine slices, carefully enclosing an apricot in each slice. Then let the Knödel cook for five to 10 minutes in a saucepan of boiling salt water. Drain. During this time, melt the butter in a frying pan and brown the breadcrumbs over a low flame. Then roll the Knödel in bread crumbs and sprinkle with sugar before serving.

When all is said and done, pour yourself a glass of Eiswein — a type of dessert wine produced from grapes that have been frozen while still on the vine — and together with Mahler’s dumplings enjoy the bittersweet irony of the hunter’s funeral.