Edward Elgar (1857–1934) was commissioned by the Royal Philharmonic Society for a work and in 1901 he created Cockaigne, subtitled, ‘In London Town’.

Edward Elgar, ca 1900

The concept of Cockaigne comes from medieval myth, where it is the land of good food, comfort, and leisure, in short, the complete opposite of daily peasant life. It was an appreciation of what could be.

In his painting of 1567, Pieter Bruegel the Elder depicted Het Luilekkerland (The Lazy-Tasty Land), known in English as The Land of Cockaigne, depicting people from three walks of life. A clerk, a peasant, and a soldier have succumbed to the gluttony and sloth, two of the seven deadly sins. All the tools of their trades (papers and ink, the harvest flail, and the lance and gauntlet) lay idle. Food is everywhere – the hut is roofed in pies, a pig with a ready knife runs by, a fowl lies down on a serving tray, and an egg on legs has a spoon ready for tasting. In the background, a man emerges having eaten his way through a cloud of pudding.

Pieter Bruegel, the Elder: Het Luilekkerland (The Lazy-Tasty Land; The Land of Cockaigne), 1567 (Munich, Alte Pinakothek)

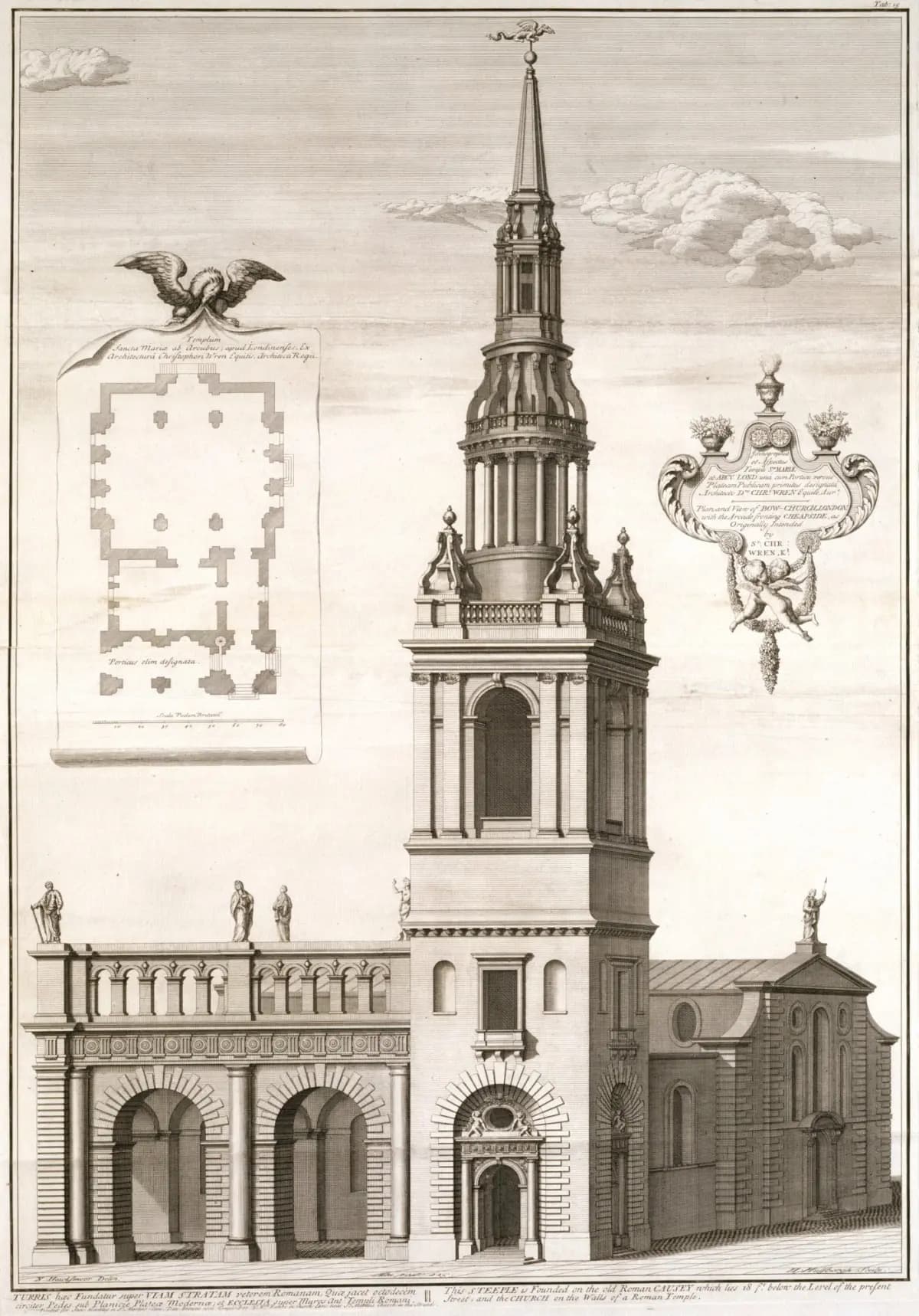

London took on the nickname of ‘Cockaigne’ from the 1820, a back derivation of the name as the land of the Cockneys. The term Cockney started as a derogatory name given to the city dwellers by rural Englishmen, first documented in 1520. By 1600, this name was associated with the area around the Church of St Mary-le-Bow in Cheapside. By 1617, writers were considering anyone born within earshot of the bells a true Londoner, a Cockney.

Nicholas Hawksmoor: Christopher Wren’s St Mary-le-Bow Church plan and perspective, ca 1720–23 (London: Royal Academy of Arts)

Elgar’s addition of the subtitle, In London Town, to his Cockaigne overture re-emphasizes the connection between imagined and real lands of delights. The theme came to Elgar while on a visit to London and the Guildhall and from that idea came the entire work. A second theme has been called the ‘lover’s theme’ and there’s also a bit of noise from a passing military band.

Edward Elgar: Cockaigne, Op. 40, “In London Town” (Mannheim National Theatre Orchestra; Alexander Soddy, cond.)

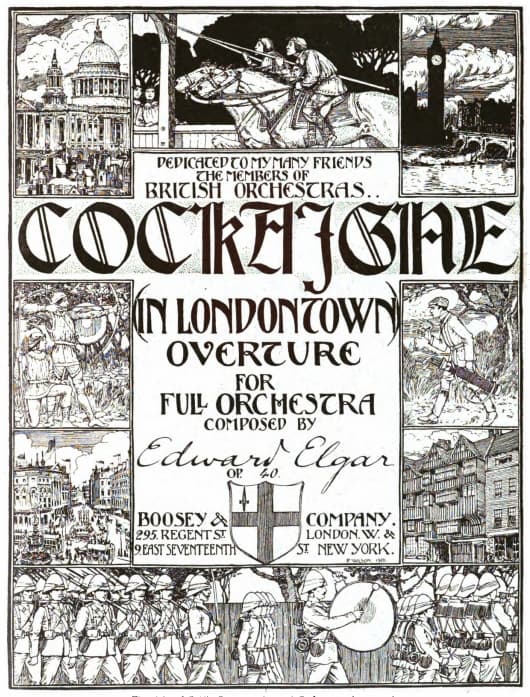

The original cover for the score is in keeping with the Breugel idea of the workers of the world: medieval knights jousting, hunters with bow and arrow, streets full of commerce (Oxford Circus at lower left), a British military band, and, to replace the man emerging from the pudding, a golfer searching for his lost ball. At the top corners, St. Paul and Big Ben (or, as it was renamed in 2012, Elizabeth Tower) at Westminster. The physical emblems of the city in its buildings are filled with the activities of its citizens: religion, governance, and shopping.

Elgar: Cockaigne, Boosey & Co.,1901 (Harvard University Libraries)

Note the dedication ‘To my many friends, the members of British orchestras’. Since this was a commission by the Royal Philharmonic Society, it was another way of thanking his commissioners. The work was given its premiere at the Philharmonic Society’s concert on 20 June 1901.

The work is busy and happy, seeming to take us through a day in town – bustling with people and yet with the ability to catch our ear with small vignettes, such as the lover’s theme.

Lest we forget what Bruegel was illustrating, Elgar added a line at the end of the score from the medieval poem Piers Plowman (‘metelees and moneless on Malverne hilles) (meatless and moneyless on Malvern’s hills), commenting on his usual physical situation in the countryside.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter