The first image we have of Beethoven after his death is his death mask. It was common to take a death mask of famous people, either to serve as a memory or as a basis for portraits. The method was the same as for life masks, although the allowance for the subjects to breath no longer had to be followed. The features of the subject are often distorted because the musculature to hold up the weight of the plaster is no longer there. Death masks can be found as far back as ancient Egypt as part of the mummification process. Death masks of famous people such as Dante, Napoleon, Joseph Haydn, Franz Liszt, and Stalin were all made.

Beethoven’s death mask by Joseph Dannhauser shows his shrunken face as compared to how he appeared in life.

Dannhauser: Beethoven Death Mask (1827)

Let’s skip forward some 30 years and see how Beethoven becomes an image in the collective memory.

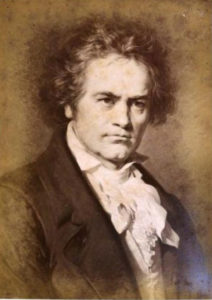

In 1854, Emil Eugen Sasche did an engraving of Beethoven for a collection of 200 portraits and life stories of famous German men. It’s clearly based on the 1820 Stieler painting, even to the lock of hair across the forehead, the style of the clothes and the loosely tied scarf at the neck, but the face lost much its character. His cleft chin is less prominent, the mouth holds less of a pout, and the collar doesn’t push his jawline. Beethoven is being normalized.

Madsen: Variations and Fugue on a theme by Beethoven, Op. 28 (Jens Harald Bratlie, piano)

Sasche: Beethoven (1854)

Jumping another 30 years ahead, we have a painting from the 1870s by Karl Jäger of Beethoven. This one has the earlier neckcloth design but all extra ornaments are missing: there are no buttons on the coat. Jäger was known for his grisaille style of work, where the painting is executed solely in shades of grey or similar neutral colour. This was created for a book by the music critic Eduard Hanslick, Gallerie deutscher Tondichter (Gallery of German composers).

Jäger: Beethoven (1870s)

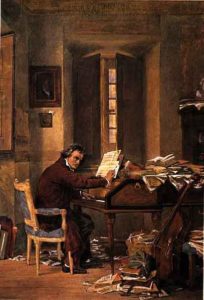

In 1890, we have an image of the great man at work – manuscripts and scores littering the floor and the piano, he in a long coat, pencil on a score and left hand on the piano. A cello or a viola da gamba stands on the right. We don’t need to have a close-in of the face to know who is the subject here. Carl Schloesser specialized in these busy interiors, although most of his paintings have a number of figures in them.

Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 14 in C-Sharp Minor, Op. 27, No. 2, “Moonlight”: I. Adagio sostenuto (Margaret Leng Tan, 2 toy pianos)

Schloesser: Beethoven Composing (1890)

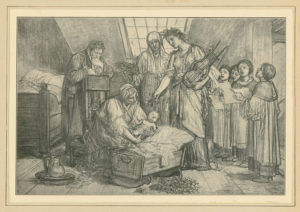

Carrying the mythologizing further, we have Friedrich Geselschap’s 1898 draft for an allegorical painting on the birth of Beethoven, attended by a small boy choir and a Muse. We can see from here that Beethoven got his hair from his father’s side of the family.

Geselschap: Beethvens Geburt (1898)

Coming into the 20th century, we have Fidus’ design for a temple to Beethoven. The image is clearly taken from the life mask, but the eyes have been more defined, working around the necessary eye patches for the casting, he’s had hair added, and his clothes are pure imagination. Now Beethoven has become a god, with a temple in his honour.

Heidrich: Variations on Happy Birthday: Variation 4 (after L. van Beethoven’s String Quartet No. 8 in E Minor, Op. 59, No. 2, “Rasumovsky”) (Venice String Quartet)

Fidus: Entwurf für einen Beethoven Tempel (1903)

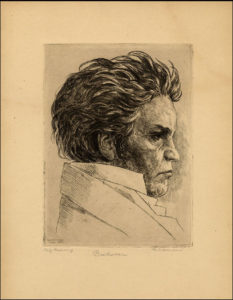

Back in 1808, Ludwig Schnorr von Carolsfeld did a quick caricature sketch of Beethoven. In 1810, he did a profile picture and in 1926 Rudolf Hermann did an etching of Carolsfeld’s work.

Hermann: Beethoven after Carolsfeld 1810 (1926)

The last 3 images of Beethoven are caricatures. What is the late 20th century image of Beethoven? Well, it’s all about the hair, the chin, and the wrapped throat, in the end. The first is David Levine from the New York Review of Books in 1968.

Levine: Beethoven (1968)

Next, it’s Al Hirschfeld from a 1991 record cover for RCA. We have the CHIN, the HAIR, and the wrapped throat.

Hirschfeld: Beethoven (1991)

And finally, it’s the 21st-century Beethoven by Franz Eder: chin: check; hair; check and in 2 colours; high collar: check. This image, however, is probably the first in 250 years to actually show Beethoven’s throat!

Beethoven, arr. Murphy: A Fifth of Beethoven (Swingle Singers; Schlomo, beatbox)

Eder: Beethoven (2009)

The problem with caricatures is that they’re all surface. They feed us what we think we know about the subject. In this 250th anniversary year, however, take the time to find your inner Beethoven, where he surprises you with his innovation, cheers you with his bucolic images, and stirs you with his heroic music.

Note: These are by no means all the images of Beethoven! Each music example here takes a work of Beethoven as reimagined by a later composer: variations on his works, new instrumentation of a work, or a vocalization of a work.