Part-time Composer  Julius Harrison: Viola Sonata in C minor

Julius Harrison: Viola Sonata in C minor

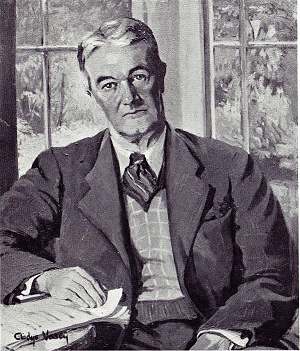

Traditionally, composers had a rather difficult time to earn a living practicing their art. A good many of them had to take a day job to actually make a living. Gustav Mahler, for example, was primarily engaged as a conductor, and his tenure with the Vienna Court Opera — he even converted to Catholicism in order to be eligible for the position — was a period of repeated battles with performers, administrators and a hostile and anti-Semitic press. While his conducting engagements and interpretive expertise paid him a handsome salary that easily covered his material needs, he spiritually longed to express himself in his own music. This was only possible in his spare time, and during summer holidays he withdrew to small composing huts in the Austrian countryside to reconnect with the sources of his inspiration. Julius Allan Greenway Harrison (1885-1963) had a similar life experience. He was an admired conductor, working with Beecham at Covent Garden, with the Scottish Orchestra in Glasgow, and in the 1930s, with the Hastings Municipal Orchestra. But he only did so in order to earn a living. When encroaching deafness brought an end to his conducting career, he finally found the time to devote himself to composition.

Harrison hailed from Stourport in Worcestershire and quickly took piano, organ and violin lessons. Already at age 16, he was appointed organist and choirmaster at Areley Kings Church, and at age 17 he conducted the Worcester Music Society in a performance of his own Ballade for Strings. Harrison introduced himself to a wider audience with his 1908 cantata Cleopatra, a work that had garnered first prize at the Norwich Music Festival. Although some reviews recognized Harrison’s talent, the work was criticized for an “overelaborate orchestration” and described as “a series of pictures of unbridled passion devoid of all that ordinary people call beauty.” Once Harrison arrived in London, his conducting career began in earnest. Engaged at Covent Garden, he was assistant conductor to Arthur Nikisch, and later to Felix Weingartner in Paris. Appointments with the Beecham Opera Company, the Scottish Orchestra and the Bradford Permanent Orchestra quickly followed, and by 1922 Harrison was conductor for the British National Opera Company. The music of Richard Wagner became his specialty, and he was appointed director of opera and professor of composition at the Royal Academy of Music. He returned to conducting in 1930, and after a slew of appointments from around the country, he accepted a post with the BBC Northern Orchestra in Manchester. Slowly his hearing began to deteriorate, and in 1947 Harrison conducted his final concert at the Elgar Festival in Malvern. He retired in Harpenden in Hertfordshire, and devoted his final years to composition. Influenced by Brahms and Vaughan Williams, he wrote a series of substantial compositions, among them Bredon Hill (1942), the Viola Sonata (1945) a Mass in C (1947) and a Requiem, which took him the greater part of a decade to finish. Geoffrey Self, Harrison’s biographer, describes the Requiem as “conservative and contrapuntally complex, influenced by Bach and Verdi respectively, with a mastery of texture and a massive yet balanced structure.” Harrison also published some writings about music, foremost a 1939 book on Brahms and his Four Symphonies, and also contributed chapters on the Symphonies by Mendelssohn, Schumann, Brahms and Dvořák. Regrettably, much of Harrison’s oeuvre — a large number of vocal and choral as well as orchestral works, alongside compositions for chamber ensemble, piano and organ — remain unrecorded. Nevertheless, it is indeed gratifying to see what people can get done in their spare time!

More Composers

- The 100th Anniversary of Erik Satie

Celebrating a Musical Maverick Explore the French composer's revolutionary simplicity -

Georges Bizet Honouring the Legacy of a Musical Genius

Georges Bizet Honouring the Legacy of a Musical Genius -

Antonio Salieri Salieri at 200: Celebrating Five Operatic Gems

Antonio Salieri Salieri at 200: Celebrating Five Operatic Gems -

George Frideric Handel Did you know Handel once fought a duel with fellow composer Johann Mattheson?

George Frideric Handel Did you know Handel once fought a duel with fellow composer Johann Mattheson?