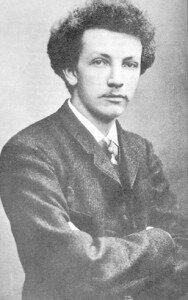

Richard Strauss

Credit: withfriendship.com

Emanuel Ax, piano

Richard Strauss: Cello Sonata in F Major, Op. 6, TrV 115

Richard Strauss was controversial as a person and as a composer, despite being one of the more prominent composers of the 20th Century. “He’d be better off shoveling snow,” said composer Arnold Schoenberg. Two of Strauss’ operas scandalized audiences—Salome of 1905, for its final scene where Salome declares her love to – and kisses – the severed head of John the Baptist, and Electra, the highly modernist and expressionist 1909 opera based on ancient Greek mythology. A 1907 letter, in New York Times said of Salome “It is a detailed and explicit exposition of the most horrible, disgusting, revolting and unmentionable features of degeneracy that I have ever heard, read of, or imagined.”

Strauss’ lushly orchestrated symphonic tone poems are tamer— Don Juan, Ein Heldenleiben and Also Sprach Zarathustra (made mainstream when it was used in the movie “2001’). We don’t associate Strauss with chamber music but he did write two piano trios, a piano quartet, a string quartet, a violin and piano sonata and a cello sonata as well as numerous “lieder” or songs and the Metamorphosen for 23 solo strings— exquisitely beautiful, intimate works.

I grew up hearing my father practice Strauss’ Cello Sonata in F Major, Op 6. It is a difficult work, challenging both for the cello and the piano, and it isn’t performed as often as the Beethoven cello sonatas or the Brahms sonatas. I remember that my father performed this piece when my brother and I were quite young, for a series at one of the art galleries in Toronto. A matronly lady said to my mother afterwards, “Madame may I congratulate you on your children,” evidently expecting us to misbehave. My mother’s response was classic, “They better listen nicely. It was their daddy playing!”

Strauss’ father was principal horn in the court orchestra of Hoforchester in Munich, so it was no surprise that Richard was started on the piano by the age of four, learning to read music before he learned his alphabet. He was composing by the age of eight! Richard was encouraged to listen to the music of classical music masters such as the Beethoven, Mendelssohn and Schumann and their influence is evident in Strauss’s cello sonata.

Hans Wihan

Credit: deposit.ddb.de

The beginning of the piece is heroic, opening with big 4-note chords introducing the lovely lyrical theme, which follows. Strauss makes use of the entire upper range of the cello—leaps in the lines that put fear in the hearts of many cellists! I love this movement for its wide range of emotions—the heroic verve and vitality of the opening, then agitation, and gorgeous expressiveness. In the middle of the first movement there is even a fugue, a structure that was popular with Beethoven.

The second movement is dark, brooding, more introspective, and yet, instead of featuring the lower range of the cello, Strauss writes quite high up the ‘A’ string, or the uppermost string, on the instrument again challenging the cellist. This movement reminds me of Beethoven’s funeral marches.

The finale returns to the heroic vein with grand leaps in the cello part. The performers need stamina for this virtuosic, intense movement. I surely never thought I could play the piece when I heard my dad practice this piece furiously. Eventually, I performed it too and it is a favorite of mine to perform, no doubt in part because of the fond memories I had of hearing my father playing the piece when I was a child.

Audiences are surprised when they see Strauss on the program of a cello recital, but they are quite gratified to hear Strauss in this more transparent form. Despite the fact that Strauss was a teenager when he composed the sonata, it is a fully developed romantic work with constantly changing textures, tone colors, and depth of expression.

Comments