Tomas Luis de Victoria

Domine ad adjuvandum me festina

Cristóbal de Morales

Missa Benedicta es caelorum regina (excerpts) (1544)

Antonio de Cabezon (Click here for our related “In love” article)

Extraordinary artistic achievements in music, art and literature created a “Golden Age” in Spain in the 16th and 17th centuries, paralleling the rise and decline of the Spanish Habsburgs’ political power and influence in Europe. Many of Spain’s most famous artists were in the employ of the Royal court, the Spanish aristocracy and the church – their fame not only reaching beyond the borders of their own country in their own time, but becoming important for European artists in the 19th and 20th centuries.

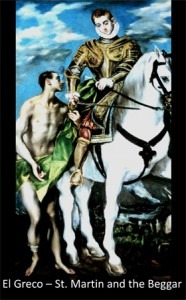

El Greco arrived from Crete via Italy and settled in Toledo, coming from a tradition of Greek orthodox icon painting, which explains to some extent his elongated figures, with small heads and almost two-dimensional forms. In St. Martin and the Beggar, we see a shift in perspective with the hind legs of the horse pushing towards the front legs. The elongated figure of the beggar defies all of the rules of traditional Renaissance perspective, situated into the landscape of Toledo, where, as in many of El Greco’s paintings, as many critics would point out later on, ‘the sun never shines’.

This artificial light illuminates all of his portraits and landscapes. In the Apostle St. Bartholomew, we also notice El Greco’s loose handling of the paint brush, which seems almost ‘impressionistic’. It comes as no surprise that his paintings, forgotten in the ensuing centuries, were rediscovered by painters of 19th century France, such as Delacroix and Manet.

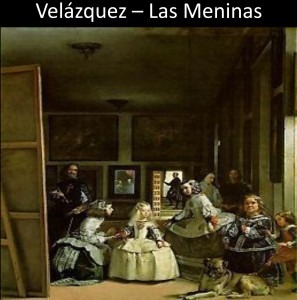

In his paintings Las Meninas, The Old Woman Frying Eggs and Menippus Diego Velázquez also raises the question of ‘reality and illusion’. Regarding Las Meninas, the French writer Théophile Gautier asks the pertinent question: “Where is the painting”? Who is the real subject of the painting? Velázquez, at his easel on the left, is looking out at us, the audience, and is at once the observer and creator of this perfectly composed scene. The handmaidens and the Infanta are in front of him, and the king and queen of Spain, reflected in the mirror behind him — all at an impossible angle to be the subject of the painting, the actual subject remaining a true mystery. The light sources here also come from different and opposite angles. As the poet Quevedo would observe, “There are many things here that seem to exist and have their being, and yet they are nothing more than a name and appearance”.

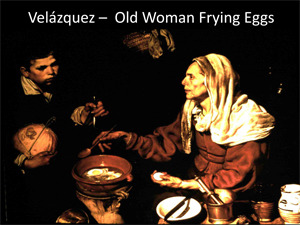

Velázquez’ other paintings show Menippus, the Greek cynic and satirist, as a beggar in an unusual pose, with a flat vase and various books at his feet, and the Old Woman Frying Eggs, in moments suspended in time, — moments of arrested motion and persuasive silence.

Everything is simply and beautifully painted, lit from some outside source, creating sharp shadows, but reducing subjects and objects to the same level of importance.

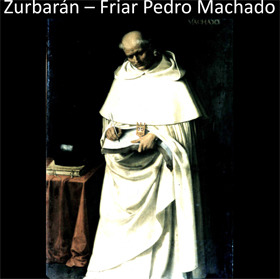

Francisco de Zurbarán, in his paintings of the Friar Machado and the Still-Life, raises the question of reality and imagination in another fashion. Zurbarán produced many paintings of monks, which inspired the following lines by Théophile Gautier:

“Moines de Zurbarán, blancs Chartreux/qui dans l’ombre glissent silencieux sur les dalles des morts/murmurant des Paters et des Avés sans nombre…”

(Zurbarán monks, white Carthusian habits/who, in the shadows glide silently over the stones of the dead/murmuring Our Fathers and Ave Marias without end…”

Rather than focusing on the different characters of the monks, Zurbarán emphasizes the materiality of ‘cloth’ and the materiality of the beautifully painted objects in the still life — highly unusual for his time. Traditional still life paintings refer to the usual concepts of still-lifes as a reflection of the fragility of life, with reference to eternity. It therefore is no accident that Zurbarán was also rediscovered in the 19th century by the Impressionists painters, with objects painted simply as objects, with no reference to eternity and the afterlife. Texture (taking Zurbarán’s painting of monk’s vestments, i.e. just ‘cloth’, as an example) was created by the paint itself.

In literature, Miguel de Cervantes introduces a new and ‘modern’ form of writing in his ‘Don Quixote’, interspersing prose and poetry and his own personal commentary and reflections. Particularly in the novel’s second part, Cervantes constantly intervenes with questions and comments on events mentioned previously. The illusions of the character of Don Quixote himself and his author raise the point of ‘reality and truth’ — similar to Velázquez, of whom Ortego y Gasset said: “I see in him a man who knew in the most exemplary fashion how not to exist…” — which makes Don Quixote the first modern novel, as it was recognized by the writers of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Relating the art and literature of this time to its music, it is said that some of Spain’s greatest music was written in this period. Spanish composers of the time, including Tomás Luis de Victoria, Cabezón (please read our related “In love” article), Morales and many others, introduced many new forms of composition, which would influence the music of the Baroque in Italy and other countries. The question of reality and illusion, presentation and silence carried into the performance of the famous Castrati singers at the Spanish court – leaving the meaning of their songs and interpretation open and changeable from performance to performance. The importance of Spain’s ‘Golden Age’ in painting, literature and music carries on into the following centuries, which will be the focus of our next articles.