We still don’t know for certain, but Henry Purcell, the most original English composer of his time, was probably born on 10 September 1659. We do know, however, that during his life, he composed music for a wide variety of occasions, including the church, the stage, the court, and private entertainment. His compositions are deeply rooted in the English Baroque, but his willingness to learn from the present infuses his music with elements taken from Italian and French styles.

Henry Purcell

Purcell wrote a lot of sacred music for the Chapel Royal, Westminster Cathedral, and private religious fraternities. In his instrumental music, he experimented with the latest genres and trends and created gorgeous trio sonatas and some solo keyboard music.

Purcell is one of the most important 17th-century composers and one of the greatest of all English composers, Purcell is best known for his operas, semi-operas, and incidental music for the British stage. The tragic opera Dido and Aeneas of 1688 is one of the earliest known operas, and excerpts have enjoyed great popularity through the ages. To celebrate Purcell’s birthday, however, let us take a look at some of his most notable semi-operas, including Dioclesian (1690), King Arthur (1691), Timon of Athens (1695) and The Fairy-Queen (1692).

Henry Purcell: Dido and Aeneas, “Dido’s Lament”

Semi-Opera and English Opera

The terms “semi-opera” and “English opera” are applied to a particular entertainment combining spoken plays with separate episodes that include singing, dancing, and instrumental music. Featuring spectacular scenic effects such as transformations, mechanical contraptions and flying, this form flourished in England between 1673 and 1719, and it clearly demarcated between the main characters.

Main characters only speak, and minor characters, such as spirits, fairies, shepherds, and gods, only sing or dance. Music in semi-operas is usually featured in moments of the play immediately following love scenes or those concerning the supernatural. In Purcell’s semi-operas, the music is concentrated into self-contained masques, which rarely advance the plot. The music is not integrated with the spoken drama, and Purcell preferred to write for professional singers rather than actor-singers who could not do justice to his more difficult music.

Henry Purcell: Dioclesian, “Triumph Victorious Love”

Dioclesian

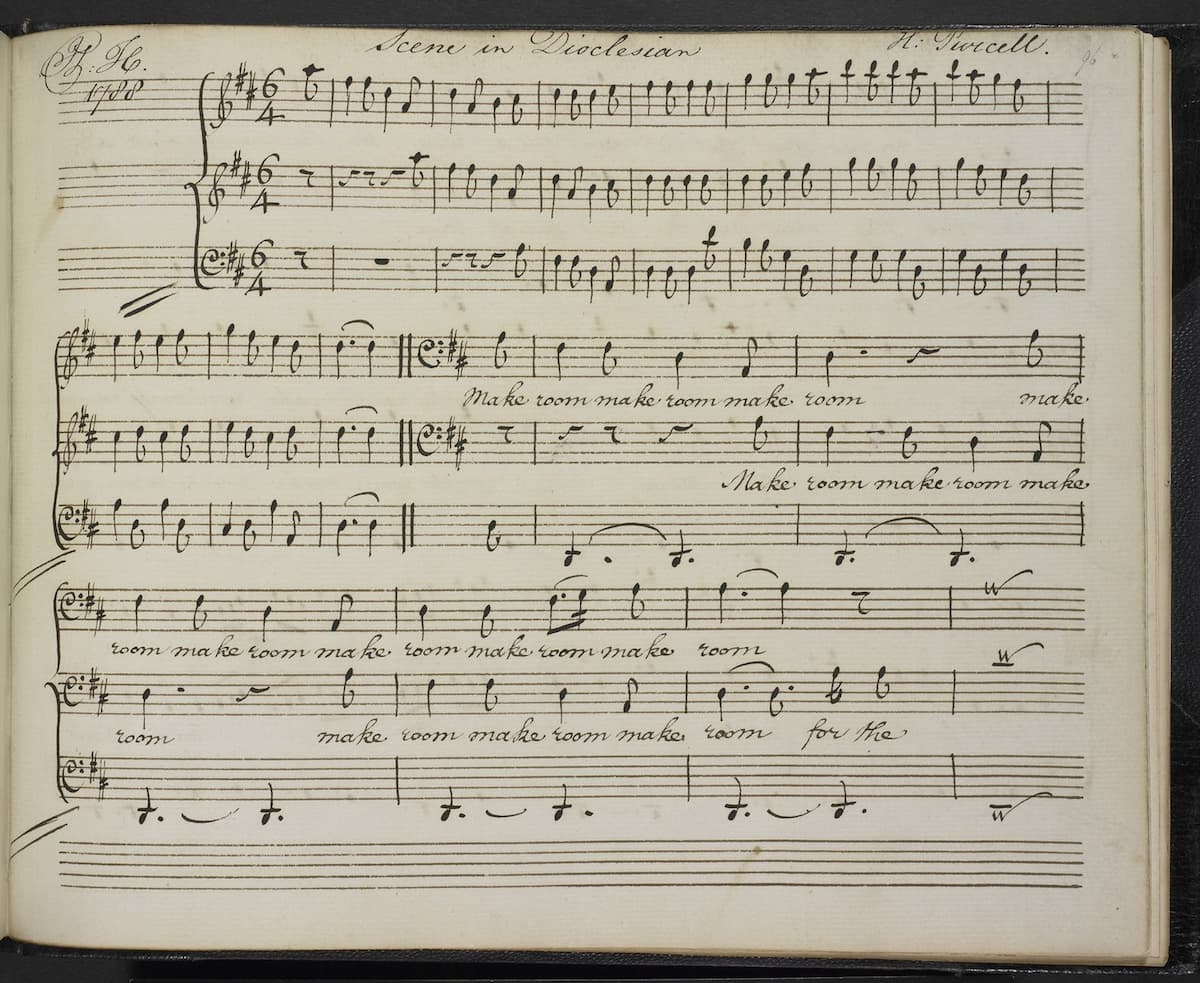

Henry Purcell’s Scene in Dioclesian

Dioclesian, as the score is known, was the only one of Purcell’s semi-operas to be published complete in his lifetime. It originated from a play by John Fletcher and Philip Massinger and was subsequently adapted by Thomas Betterton. The plot is primarily concerned with a struggle for political power in ancient Rome. The oracle Delphia predicts that Diocles, a common soldier, will become emperor after he kills a mighty boar. Diocles laughs at the prophecy and mockingly promises to marry Delphia’s ugly niece, Drusilla, if it were to come true.

As it happens in these stories, Diocles discovers that the Captain of the guard “Volutius Aper” (The Boar) has murdered the old emperor, and when he avenges the killing, Diocles is elected co-emperor. He now calls himself “Dioclesian,” and forgetting his promise to Drusilla, falls in love with the beautiful Princess Aurelia. The prophetess is not too happy and disrupts the wedding ceremony by conjuring up a dreadful monster, thunder, and lighting.

Henry Purcell: The Prophetess, Z. 627, “The History of Dioclesian” (Catherine Pierard, soprano; James Bowman, counter-tenor; John Mark Ainsley, tenor; Mark Padmore, tenor; Michael George, bass; Collegium Musicum 90 Chorus; Collegium Musicum 90; Richard Hickox, cond.)

Musical Numbers

However, Delphia isn’t done yet. She casts a spell that makes the Princess Aurelia fall in love with Diocles’ nephew and rival Maximinian. She then helps the invading Persians to defeat the Roman army. Diocles is shocked, and his counterattack finally dispels the invaders. In the process, Diocles learns humility and cedes his half of the throne to Maximinian and honours his original promise to marry Drusilla. Eventually, he retires to Lombardy and dedicates his life to virtue.

Musicologist Curtis Price considers Purcell’s music “the least satisfactory on the stage.” This assessment is based on a contemporary review stating, “How ridiculous is it in that Scene in the Prophetess, where the great Action of the Drama stops, and the Chief Officers of the Army stand still with their Swords drawn to hear a fellow Sing ‘Let the soldiers rejoice.’” However, the music is perfectly crafted and successfully captures the emotional moments. “From this plotless miscellany,” Price writes, “emerges a highly unified score in which the contrasting heroic and pastoral modes gradually converge.

Henry Purcell: Dioclesian, “Sound, Fame”

King Arthur

Henry Purcell’s King Arthur – Frost Scene

The semi-opera King Arthur, essentially a play with music, is frequently considered the most successful as it offers a more complete integration of music and drama. The libretto, a reworking of a medieval legend, was fashioned by the writer and dramatist John Dryden. He provided Purcell with opportunities for specific musical episodes, and the two main characters sang as well as spoke. As Purcell specialist Curtis Price explained, “Purcell’s music consists of six separate scenes distributed throughout the play. Unlike in other semi-operas, these musical episodes advance the plot.

The plot is based on King Arthur’s attempts, assisted by Merlin, to free his fiancée, the blind Cornish Princess Emmeline, who has been abducted by his arch-enemy, the Saxon King Oswald of Kent. It is a supernatural spectacular as we find the characters Cupid and Venus, plus the Germanic gods of the Saxons, Woden, Thor, and Freya.

Henry Purcell: King Arthur, “The Frost Song”

Musical Scenes

After a couple of overtures, the first musical scene in Act 1 addresses the sacrifice offered by the Saxons on the eve of battle. As Price writes, “Purcell constructed this exactly like a verse anthem, with solemn choral responses interspersed between solo incantations which lead to longer, developed choruses.” The battle starts immediately with the Britons taunting, “Come if you dare,” and some exciting trumpet fanfare. As the Britons pursuit the defeated Saxons at the beginning of Act II, the evil spirit Grimbald leads the attackers into “perilous rivers” and “dreadful downfalls.”

Purcell writes his most overtly operatic scene when Arthur’s men are being directed to safety while Grimbald pulls them in the opposite direction. Meanwhile, the consequences of sexual pleasure are the topic of pastoral entertainment for Emmeline. At the beginning of Act III Emmeline has her sight restored by Philidel, but she continues to refuse the advances of Osmond. He grows ever more frustrated and, through his magic powers, shows her a “Prospect of Winter in Frozen Countries.” And here sounds one of Purcell’s greatest pieces in the famous “Frost Scene,” with the singer shivering through his aria.

Henry Purcell: King Arthur (Maurice Bevan, baritone; Mark Deller, counter-tenor; Paul Elliott, tenor; Jean Knibbs, vocals; Bigel Beavan, bass; Rosemary Hardy, soprano; Honor Sheppard, soprano; Consort Deller; The King’s Musick; Alfred Deller, cond.)

Musical Scenes Acts IV and V

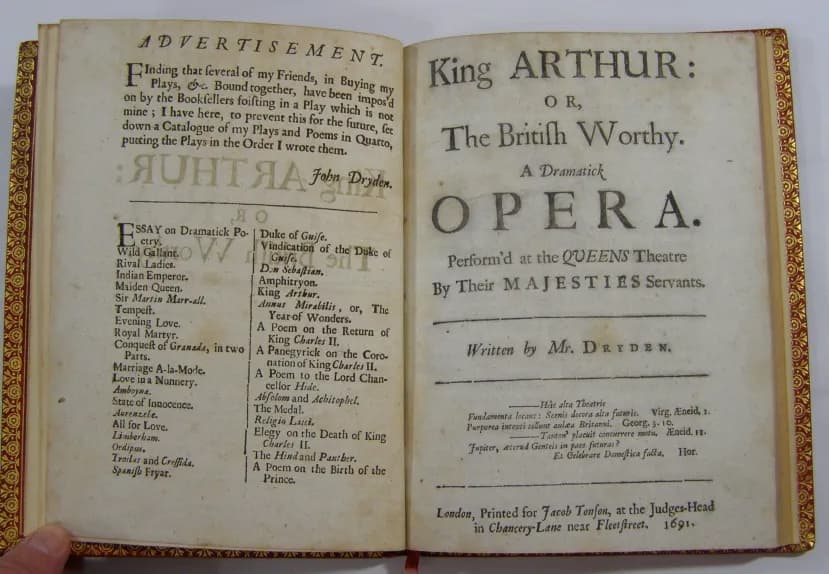

The advertisement of King Arthur

Emmeline is still in captivity during Act IV, with Arthur’s rescue attempt repelled by Saxon magic. As Price writes, “The centrepiece of the act (indeed, of the entire work) is the massive passacaglia ‘How happy the lover,’ one of Purcell’s longest compositions. It is built on a four-bar ground bass (repeated 59 times in various forms) with a succession of solos, duets, trios, choruses and instrumental interludes.”

Arthur finally defeats the Saxons in Act V, and he even forgives Oswald. He tells Oswald that he must return to Germany because the Britons “brook no Foreign Power.” As the sorcerer Osmond is cast into a dungeon with Grimbald, Arthur reunites with Emmeline and the work ends with a celebratory masque, including a rollicking folksong, “Your Hay it is mow’d,” followed by a nostalgic air.

Henry Purcell: King Arthur, “Passacaglia”

Timons of Athens

Henry Purcell’s Timon of Athens

For a revival of the Shakespearean play Timon of Athens in 1677/78, Thomas Shadwell was asked to revise it. Shadwell went to work and re-wrote the entire play in his own words, adding some love interest with a mistress and a jealous fiancée for Timon. The play was eventually called “The History of Timon of Athens, The Man-Hater.” In 1694, the play was revived once more, and Henry Purcell was asked to write some incidental music for the play.

Purcell composed his music in such a way as to turn the masque into an essential part of the drama. The poem features shepherds, nymphs, and Bachants in an argument over the relative merits of addiction to wine and love. A commentator wrote, “It is an allegory of the main plot of Timon’s struggle between his two would-be loves, one a hedonist and the other a stoic.’

Henry Purcell: Timon of Athens (Iestyn Davies, treble; Christopher de la Hoyde, treble; Michael George, bass; James Bowman, alto; John Mark Ainsley, tenor; Collegium Musicum 90 Chorus; Collegium Musicum 90; Richard Hickox, cond.)

Musical Numbers

Purcell’s musical setting includes an Overture, 12 vocal numbers, and a Curtain Tune on the Ground. A trumpet overture, full of dotted rhythms and fanfare music, gets things going. With plenty of counterpoint between the voices, the overall effect is one of sophistication. Interestingly, Purcell reverses the usual order for such overtures by opening with a happy Allegro before closing with a delicious Adagio. The opening duet features two followers of Cupid, while the bass solo for Bacchus is highly picturesque.

“The Cares of Lovers” was a particularly popular song, and it sounds like some of the Italian influences on English vocal music. These influences are heard throughout the vocal numbers. Purcell was a consummate master of the passacaglia, and the “Curtain Tune” sounds nine variations, each based on the same harmonies. Purcell’s harmonies are marked by definitive cadences and modulations. In the story, Timon has been struck by tragedy and becomes a recluse. The music in Timon of Athens was one of Purcell’s most popular, “although not one of his finest creations.”

The Fairy Queen

The Fairy Queen

Purcell’s third semi-opera The Fairy Queen was the most lavish and expensive show of the decade. Based on Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Purcell did not set any lines from the play, and all the music is in self-contained masques with little effect on the play. The anonymous transformation of the play into a semi-opera, however, is skillfully handled and makes ample room for Purcell’s wonderful music.

Since the plot of the play A Midsummer Night’s Dream is fairly well known, let’s focus on the scenes in which Purcell provided music. The first scene set to music occurs after Titania has left Oberon over an argument over the ownership of a little boy. While two fairies sing of the delight of the countryside, a drunken and stuttering poet enters. The fairies mock the drunken poet and drive him away.

Henry Purcell: The Fairy Queen, “Chaconne: They shall be as happy as they are fair”

Other Masques

The second scene follows Oberon’s command to Puck to anoint the eyes of Demetrius with the love-juice. Titania and her fairies engage in merrymaking until they are lulled to sleep and left with pleasant dreams. In the third masque, Titania has fallen in love with Bottom, now sporting his ass’ head. A Nymph sings of the pleasures and torments of love, and after several dances, Titania and Bottom are entertained by two haymakers, Corydon and Mopsa.

After Titania is freed from her enchantment, masque IV opens with a brief divertissement to celebrate Oberon’s birthday. However, the majority of the music is allotted to the god Phoebus and the Four Seasons. The final masque begins after Theseus has been told of the lovers’ adventures in the woods, and the goddess Juno sings, “Thrice happy lovers.” A Chinese man and woman enter, singing several songs about the joys of their world, and two other Chinese women summon Hymen, who sings in praise of married bliss.

Henry Purcell: The Fairy Queen, Z. 629 (Miriam Allan, soprano; Corin Bone, baritone; Sara Macliver, soprano; Sally-Anne Russell, mezzo-soprano; Simon Lobelson, baritone; Jamie Allen, tenor; Paul McMahon, tenor; Brett Weymark, tenor; Belinda Montgomery, soprano; Alison Morgan, soprano; Stephen Bennett, bass; Cantillation; Orchestra of the Antipodes; Antony Walker, cond.)

Conclusion

Portrait of Henry Purcell

The Fairy Queen and the essentially plotless masques are far removed from opera. Yet, as a scholar writes, “Purcell seems completely at ease with the medium. The music displays a coherence, a harmonic and motivic unity extending even to the instrumental act tunes which are lacking in the other semi-operas.” The vocal parts are certainly more difficult because Purcell was writing for professional singers. “The Fairy-Queen is not a corruption of Shakespeare’s play but rather an extended meditation on the spell it casts.”

Henry Purcell wrote music for about 50 plays, but the semi-opera died out because of theatre politics. Once Italian opera had been introduced to the London stage in 1705, the two competing opera houses were unable to pay the high salaries demanded by foreign singers. The politicians stepped in and ordered a separation of genres between the two houses. Drury Lane was permitted to put on plays but without music, while the Haymarket could produce any kind of opera. Thus, the semi-opera disappeared, as both actors and singers were required.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter