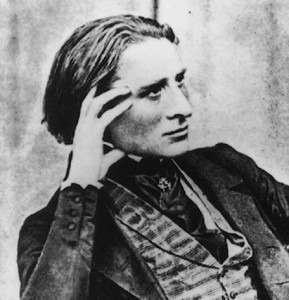

Liszt

Liszt

After a highly successful tour of Russia, Franz Liszt arrived in Berlin and played his first recital at the Berlin Singakademie on 27 December 1841. His performance style had earlier been described in the following way: “M. Liszt’s playing contains abandonment, a liberated feeling, but even when it becomes impetuous and energetic in his fortissimo, it is still without harshness and dryness. [He] draws from the piano tones that are purer, mellower and stronger than anyone has been able to do; his touch has an indescribable charm.” Maybe it was Liszt’s delicate touch and charm, or even his handsome profile, which led to fainting spells among female listeners during his Berlin performances. Subsequently dubbed “Lisztomania” by Heinrich Heine — and colloquially referred to as Liszt-Fever — this phenomenon began to be seen as a medical condition that was extremely contagious. However, Heinrich Heine offered an alternate, and surely more plausible explanation. “A physician, whose specialty is female diseases, and whom I asked to explain the magic our Liszt exerted upon the public, smiled in the strangest manner, and at the same time said all sorts of things about magnetism, galvanism, electricity, of the contagion of the close hall filled with countless wax lights and several hundred perfumed and perspiring human beings, of historical epilepsy, of the phenomenon of tickling, of musical cantharides, and other scabrous things, which, I believe have reference to the mysteries of the bona dea. Perhaps the solution of the question is not buried in such adventurous depths, but floats on a very prosaic surface. It seems to me at times that all this sorcery may be explained by the fact that no one on earth knows so well how to organize his successes, or rather their mise en scene, as our Franz Liszt.”

Charlotte von Hagn

It is not known whether Charlotte von Hagn, a Bavarian actress in the Berlin Hofbühne fainted during one of Liszt’s concerts; but she certainly caught Liszt-Fever! Known for possessing great talent for comedy that was based on her beauty and demeanor, Charlotte was described as witty and charming, which earned her the nickname “the German Déjazet,” an endearing reference to the famous Parisian actress Pauline Virginie Déjazet. But it was not conversation that first attracted Franz to Charlotte. Rather, Charlotte composed a love-poem and had written it on the corner of a hand fan. Following his first Berlin performance, Charlotte presented the fan to Franz. The poem is a discussion about love between a poet and in inquirer, who poses two questions for the poet to answer.

| Was Liebe sei Dichter! was Liebe sei, mir nicht verhehle! Liebe ist das Atemholen der Seele. Dichter! was ein Kuß sei, du mir verkünde! Je kürzer er ist, um so größer die Sünde! | What is Love? Poet, what is love? Will you not tell me! Love is when the soul takes a breath. Poet, what is a kiss? Do tell me, please! The shorter it is, the greater the sin! |

Liszt could neither resist Charlotte nor the poem; she quickly became his lover and Franz used the poem in three separate song-settings on the same text; the first version dates from 1844, the second from 1855, and the final version from 1878. Several years later, when Charlotte was married to Baron von Oven, she wrote to Liszt, “You have spoiled all others for me. No one can stand the comparison.” This statement might actually account for the fact that her marriage only last three years. Liszt, on the other hand, called Charlotte “the concubine of two kings.” Clearly Franz thought of himself as royalty, so that would account for one of the kings. The other royal was the Bavarian King Ludwig I. Charlotte had met King Ludwig shortly after her 17th birthday, and after a quickie tryst the smitten aristocrat commissioned the royal painter Joseph Karl Stieler—who in 1820 had painted one of the most famous Beethoven portraits—to fashion a painting of Charlotte. Completed in 1828, the painting portrays Charlotte as the character of Thekla from Schiller’s poem “Wallensteins Camp,” one of Ludwig’s favorite pieces of literature. Ludwig ordered the painting to be hung in his “Schönheitengalerie” (Gallery of Beauties), located in the south pavilion of his Nymphenburg Palace in Munich. The collection contains 36 portraits of the most beautiful women from the nobility and middle classes of Munich, among them also a certain Lola Montez. Ludwig had a passionate affair with Lola, and so did Franz Liszt! I tell you about that relationship a bit later.