Henri Casadesus, Lucien Capet, Marcel Casadesus, Maurice Hewitt

Credit: Wikipedia

Music – an evanescent art – left few traces prior to the development of player pianos and recording technology around 1910….and most musicians, whether famous or obscure, were too busy, protecting or advancing their careers, to document the ups and downs of their lives for posterity. After all, they could not count on pensions to cushion their retirement, and many celebrated geniuses – not attentive enough to financial security – ended their years in dire straits.

Yet, the secrets of past masters are not now as irretrievable as they once were. We simply have to know whom to listen to, and what to listen for!

The intensity of musical life during this period defies all expectations, and, despite the reduction in aristocratic and Church patronage during these republican and anti-clerical decades, we find Paris Conservatoire violin professors from humble backgrounds, Jean-Pierre Maurin (1822-1894) and Jules Garcin (1830-1896), able to afford Stradivarius violins for most of their careers. This is understandable only in the context of a general impoverishment of Italy for fifty years following the 1815 defeat of Napoleon. As of 1827, the Lombardian violin collector Luigi Tarisio started supplying Paris restorers with abandoned instruments from all over northern Italy, and following his death in 1854, the foremost Parisian restorer Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume (1798-1875) purchased the entire stock of 144 instruments, including 25 Stradivari, for a mere 80,000 francs (approx. 350,000€ today)!

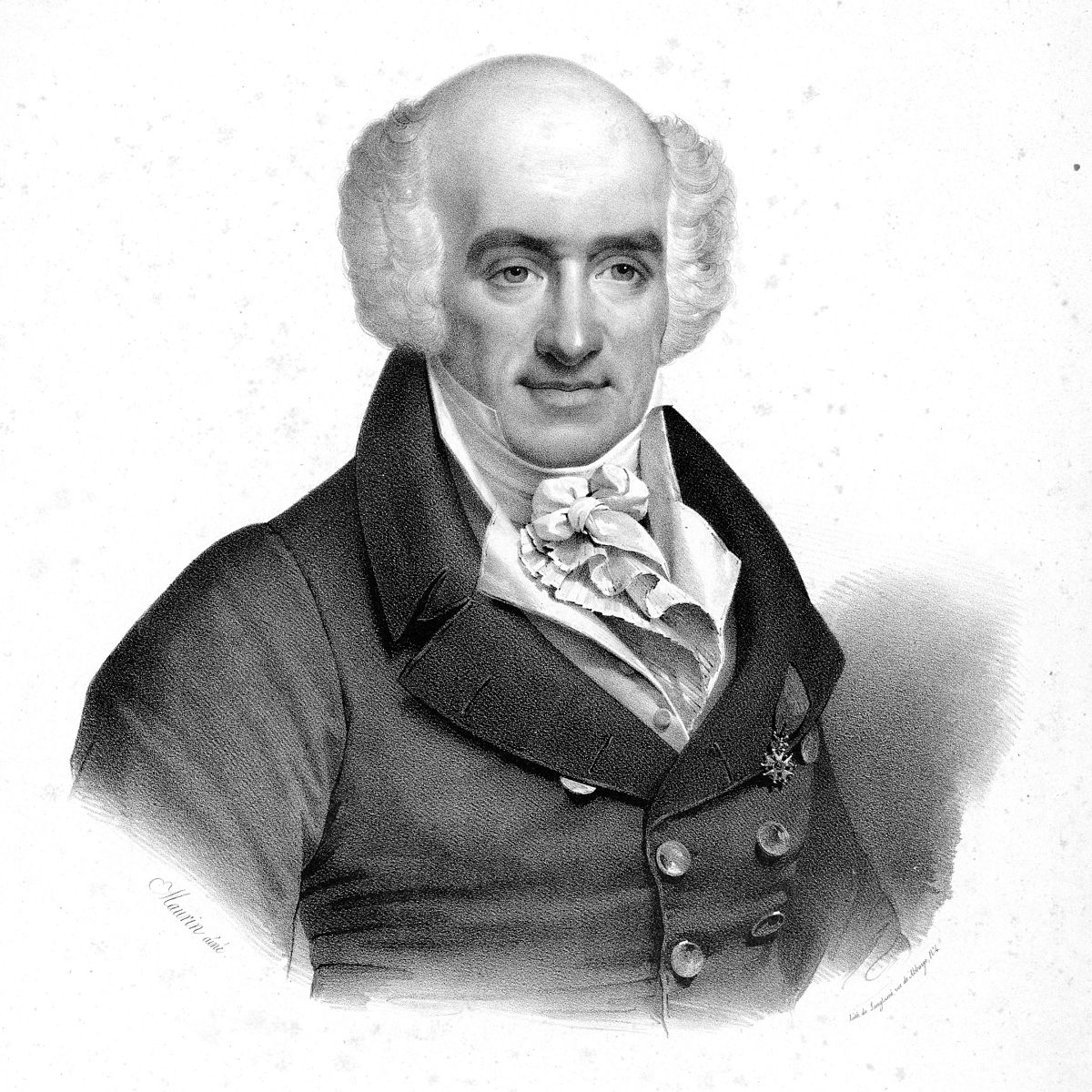

Lucien Capet

Credit: http://1.bp.blogspot.com/

Clans of disciples would form around senior composers, virtuosos and impresarios, to seek musical guidance and social introductions to generous admirers, but also to support each other against the vitriolic criticism dished out at close quarters by rival clans – even a friend’s friend could be one’s worst enemy! Such was the experience of an ostracized Ravel, who courageously collaborated in setting up the Société Musicale Indépendante, presided by Fauré, to promote the music of Debussy, Ravel, Kodaly and of the penniless Satie, in the face of relentless sniping by critic Pierre Lalo, son of composer Edouard Lalo (1823-1892), a Fauré family friend.

Despite the constant betrayals however, suicide was rare in these circles – instead, revenge consisted in coming up with fabulous new compositions, forcing the opposition to eat its words; while others let off steam by composing in the heat of anger, like Louis Vierne (1870-1937) whose 3rd Organ Symphony was a violent reaction to being overlooked for the prestigious post of Directeur du Conservatoire in 1911, due to his blindness.

Contrary to the promotional verbiage in vogue today, artists involved in those decades of heaving creativity let their works promote themselves. They lived hand to mouth, and had no time to keep a diary of their historically significant experiences. It’s only after the Second World War that survivors sought to convey the achievements of that vanished cultural order to a new generation seeking authenticity.

Foremost among these, the influential French conductor Pierre Monteux (1875-1964) always seemed to be at the right place at the right time, linking otherwise disparate episodes of musical development. His high profile corresponded perfectly to the notion of pedigree in music: he entered the Paris Conservatoire age nine, and at twelve set up an ensemble of his fellow violin students, including future celebrities Jacques Thibaud, Georges Enescu, Fritz Kreisler and Carl Flesch to accompany their pianist colleague, ten years old Alfred Cortot, in public performances of concertos! His teachers were the above-mentioned Jules Garcin (who conducted the premiere of Franck’s Symphony in D) and Albert Lavignac who taught music theory to Debussy, d’Indy, Pierne, Schmitt and Henri Casadesus.

Monteux performed for Franck, Brahms and Fauré; he played with Saint-Saëns and Ravel, and received instruction directly from Debussy and Stravinsky. He, in turn, trained up a significant proportion of post-War conductors, and left countless bench-mark recordings covering much of the standard repertoire.

The transition to the era of recorded sound is in every way equivalent to the distinction between history and prehistory: written records dispel the silence, reveal intentions and methods of action – and though technological improvements can now make stones and bones talk, the charm of Mozart’s touch and the power of Beethoven’s declamation remain irretrievably lost.

It is as a spokesman for his colleagues of the Franco-Belgian violin school, who did not live long enough to consign their art to disc, that Monteux is central to our research.

He started his professional career as a violist in the reputed Geloso Quartet – the resident quartet of the Beethoven Society created by the conductor Charles Lamoureux in 1889. Monteux would often recount this tantalizing story of their performance for Brahms, playing one of his quartets, leading the composer to comment: “It takes the French to play my music properly. The Germans all play it much too heavily”.

What wouldn’t we give to hear a few bars of this performance, so satisfying to Brahms?! The good news is that Geloso’s 2nd violin was Lucien Capet (1873-1928) who, shortly thereafter, went on to found his own remarkable Quatuor Capet (1893-1928) which made definitive recordings of Beethoven, Debussy, Ravel, etc… the bad news is that they did not record any Brahms!

Capet had studied violin with Jean-Pierre Maurin, the above-mentioned Stradivarius-owning professor at the Paris Conservatoire who, with cellist Pierre Chevillard, founded the Maurin-Chevillard Quartet in 1852, also known as the “Société des derniers quatuors de Beethoven”; their fame was such that Cosima Liszt-von Bulow requested they play Beethoven late quartets in Lucerne for Wagner’s birthday in 1869 – the year before she divorced conductor von Bulow to marry Wagner.

By the 1890s, France had recovered its prosperity, temporarily compromised by the crushing reparations imposed on Napoleon III by Germany’s “Iron Chancellor” Bismarck, for having started – and lost – the 1870 Franco-Prussian War.

Paris had just staged the grandiose Universal Exhibition of 1889, showcasing imperial, industrial, scientific and artistic achievements, with the Eiffel Tower as its logo; here, Debussy would get his first exposure to Asian music on instruments like the gamelan. Organ builder Cavaille-Coll, piano manufacturers Pleyel, Erard and Gaveau, and a host of violin restorers, met the needs of the world’s best instrumentalists who either lived in, or regularly congregated in the French capital.

At the Paris Conservatoire, a twenty year struggle between conservatives and progressives had begun, spurred by Debussy’s return from his Prix de Rome in 1887, and the performances of his Quartet and Prélude à l’Après-midi d’un Faune in 1893 and 1894. It is usual to play up the somewhat sinister sabotage of Ravel, and to a lesser extent Debussy, by organist Theodore Dubois and composer Charles Lenepveu, forgetting that the values they supported were much the same as those espoused by Brahms, ie, the aesthetics of Bach, Handel, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven and the now respectable Berlioz.

With such a background, it is not surprising that the Quatuor Capet made the performance of Beethoven’s quartets their mainstay: the transparency of structural analysis and the expressive energy of ensemble playing make these interpretations unforgettable. Debussy, Ravel, Schubert, Schumann and Franck are also beautifully served.

Beethoven String Quartet No15 in A Minor Op132

Quartet Capet 1923

Among those contributing their services to the Capet Quartet in the early years were violinist and composer Henri Casadesus (1879-1947) and cellist Marcel Casadesus (1882-1914), uncles of the pianist Robert Casadesus (1899-1972), just a few of the many members of this influential musical dynasty of Spanish origin. In 1901, family members founded the research and performance-orientated Société des Instruments Anciens, with Henri on the Viole d’Amour, Lucette on the Viole de Gambe, Marius on the Quinton (an XVIIIth century 5-stinged violin) and Regina on the Harpsichord. This was four years before Wanda Landowska burst onto the scene with her custom-made Pleyel harpsichord.

By 1910, the Capet team had stabilised, and went on to make recordings into the late 1920s.

For Lucien Capet, however, this was far from the end of the story!

As a violin teacher at the Conservatoire, he became fascinated with the mechanics of bowing, and sought to achieve greater expression both by improving the bow’s design in contact with the strings, and by better control of arm movements. He published Technique Supérieure de l’Archet in 1916, which became the standard text within the Conservatoire.

Now, as anyone familiar with the classical music scene in Paris before 1990 would acknowledge, one found less of the prima donna culture there, than elsewhere. Secure in their hierarchical posting, it was deemed in bad taste to remind others of one’s achievements. On the contrary, the elites displayed a touching degree of solicitude towards those who sought them out. As a result, one could be too easily taken for granted, and credit not given where credit was due.

This appears to have happened to Lucien Capet, with beneficiaries of his insights believing he was merely retransmitting standard curriculum material. Through his students at the Curtis Institute, Ivan Galamian and Jasha Brodsky, and conductor Charles Munch, the Capet method has been promulgated to large numbers of elite professionals, without due acknowledgement of their sources. It is hoped that the recent (2007) first comprehensive English translation of his Technique would go some way to restoring his stature at the heart of the now world-wide Franco-Belgian violin school, and ensure a wider audience for his recordings!

Debussy String Quartet g-moll op.10