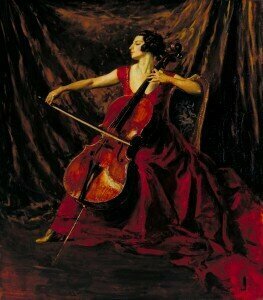

Madame Suggia 1920-3 by Augustus John OM 1878-1961

Today we are amused when we see photos of women playing the cello side-saddle—a dignified position. During the late 1800s, the cello was unwieldy to play, even for men, certainly unfeminine, until the end-pin—the metal spike extending from the bottom—was established at the end of the 19th century, liberating the player from having to hold the instrument with their knees.

Suggia began cello studies at the age of five with her father, Augusto, a distinguished cellist. She made rapid progress on a ¾ sized instrument (with an end-pin) and soon performed joint piano-cello recitals with her older sister Virginia, attaining celebrity status in the soiree scene. The girls were fortunate to be growing up in Porto, a city with a rich and varied musical life. One day in 1898, the 22-year-old cellist, Pablo Casals, came to perform. His cello recitals caused a stir, and naturally, Augusto was eager to have his young daughter play for Casals. Once Casals heard Suggia he immediately agreed to give her weekly lessons.

Guilhermina Suggia

The family tried to accommodate. Augusto gave up his career to travel with Guilhermina but financial difficulties rapidly ensued even though Virginia sent money from her piano-teaching earnings to her father and sister. Suggia had to succeed and to succeed quickly. The opportunity came in 1903—her debut with the Gewandhaus Orchestra, Arthur Nikisch conducting. The tremendous ovation that followed her performance of the Volkmann Concerto induced her do something quite unconventional. She played the entire concerto a second time! A few days later, another concert broke with tradition. The cello duo program, featured Guilhermina playing the first cello part, her teacher, Klengel, the second. What a triumph for the 18-year-old.

From 1903-1906 Suggia played in all the major centers of Europe—Vienna to Berlin, Budapest to Brussels, and then, Paris. She remained there for seven years inspired, but overshadowed by Pablo Casals.

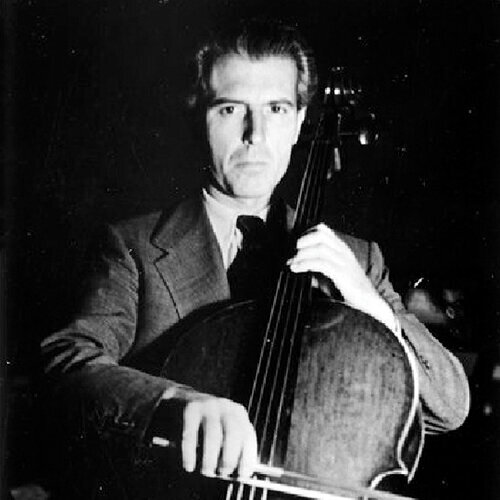

Casals and Suggia

Within a decade of her arrival there, audiences adored “La Suggia.” A consummate musician with a mesmerizing personality, perhaps the first woman soloist who might be called a diva, she dressed in the latest haute couture, which contributed to her vivid stage presence. Although at the time female cellists were derided, Suggia flaunted her femininity, and proved she could play with great power, finesse and scope.

Haydn: Cello Concerto in D – Suggia/Barbirolli 1st Recording

In 1924 Suggia returned to her beloved Porto, Portugal, and eventually married at the age of 42. Despite her marriage, she continued a busy concert schedule until World War II erupted in 1939. During the war years she suspended concertizing and dedicated herself to teaching and to volunteer work.

Suggia, returned to the concert stage in the late 1940s, by then in her sixth decade of her life. According to reports her performance at the Edinburgh Festival in 1949, “the queen of cellists …Suggia is still a supreme artist and a personality of unique distinction…the same grace of line in her bowing, the same mastery of her instrument…”

A dedicated teacher, she left part of her estate to encourage talented cellists. Each year The Suggia Prize is awarded to an exceptional cellist at the Porto Conservatory, and The Suggia Trust, established in the UK, is awarded to young cellists of any nationality. Once Suggia’s treasured 1717 Stradivarius cello was sold, the funds were bequeathed to the Royal Academy of Music in London. In 1955 a recipient of the Suggia Prize was ten-year-old prodigy, Jacqueline du Pré.

By the time Guilhermina Suggia passed away in 1950, women had become accepted as professional cellists. We owe our success to her pioneering efforts and great artistry. Moreover, she set the stage for all women performers of today, impeccable artists such as Anne Sophie Mutter and Yuja Wang, who present themselves unabashedly and with assurance.

Suggia plays Kol Nidre by Max Bruch

It is good to have a tribute to Madame Suggia, who tends to be known for her portrait alone. She recorded about 27 record sides, including movements of baroque sonatas and of the Bach C major suite, apart from the four pieces that you mention. Some of these involved as many as six takes. All this hardly ties in with your suggestion that she eschewed recording. Casals began recording for Victor in the USA in 1925; those recordings were issued internationally on HMV. Effectively Suggia was competing with Casals in the HMV recording limelight.