Belinfante Quartet Plays Bosmans

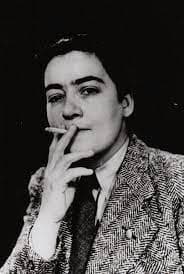

Frieda Belinfante

The Dutch cellist, conductor, and Nazi-resistance fighter Frieda Belinfante led an extraordinary life. Belinfante was born in Amsterdam in 1904, into a musical family, the third of four children. Her father was a prominent pianist who was the first to perform all 32 Beethoven piano sonatas in Holland. She began cello lessons at the age of ten. “Music was our religion.”

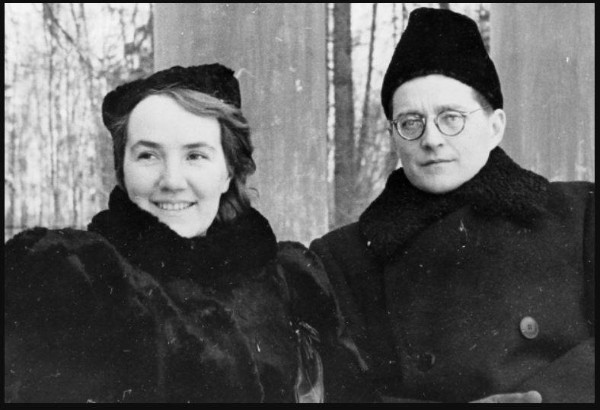

Once she graduated from the Amsterdam Conservatory, Belinfante played professionally but chose to pursue conducting. Although she admitted to being a lesbian and confessed that since the age of 16 she’d been in love with the composer and pianist Henriëtte Bosmans, she married John Falcon in 1931, a prominent flutist after he insisted he couldn’t live without her. (Bosmans actually wrote her second cello concerto for Belinfante and was her partner for many years.)

Henriëtte Bosmans: String Quartet (Utrecht String Quartet)

John took Belinfante under his wing and the couple made music together. By 1937 Belinfante was invited by the Concergebouw management in Amsterdam, to form and direct a chamber orchestra, a position she held until 1941—the first woman to conduct a professional ensemble in Europe. Belinfante also appeared with the Dutch National Radio and other orchestras of Europe as a guest conductor. The Nazi occupation of The Netherlands in May 1940, soon put a stop to her musical aspirations. She was partly Jewish and the members of her orchestra were both Jewish and non-Jewish, which was forbidden. Moreover, Belinfante, unapologetic about who she was during the decades when intense homophobia existed, risked arrest.

Frieda Belinfante and Henriëtte Bosmans

Her friendship with Willem Arondeus the leader of a Dutch Nazi resistance group, an openly gay man, led her to join their efforts. She was after all, divorced, openly gay, and half-Jewish herself. Forging precious documents to allow Jewish people to escape the clutches of the Nazis, and circulating leaflets took courage. But the false documents her group had been forging, as many as 70,000 false IDs, could be compared to the originals in the archives. In March 1943, she hatched a plan to bomb Amsterdam’s population registry office, which held original Jewish ID records—one of the most daring actions of the war. Even within the resisters gender played a role. Prohibited from actively engaging in the raid since she was a woman, she did not participate in the successful firebombing. Thousands of records were destroyed but the eleven perpetrators were caught and executed, Arondeus among them. Before he died he asserted, “Homosexuals are not cowards.”

Belinfante narrowly evaded capture. Realizing the cell group had been betrayed, she didn’t go home, and disguised herself as a man. As a fugitive, wherever she found shelter Belinfante knew she risked jeopardizing others. Belinfante eventually fled. With the help of the French resistance, she and a fellow resister crossed the alps on foot—through four countries and through deep snow, ice, and across a frigid river to Switzerland—a grueling trek taking three months. Once there, the border police picked her up and incarcerated her first in jail, until her swollen knees recovered from the arduous journey, then in a Swiss refugee camp where conditions were dismal. She thought she would never play music again.

Belinfante managed to start a choir, coercing people to sing, and a cello was rented for her. Music offered some solace. Soon rumors circulated that Belinfante was a lesbian and here too she was ostracized.

Belinfante managed to start a choir, coercing people to sing, and a cello was rented for her. Music offered some solace. Soon rumors circulated that Belinfante was a lesbian and here too she was ostracized.

Not until the war ended did Belinfante return to the Netherlands. Her apartment had been sealed by the Gestapo. After learning about the deaths of close colleagues she’d performed with, and resisters she’d collaborated with Belinfante emigrated to the US in 1947.

She joined the music faculty of UCLA in 1949, teaching cello and conducting and she became the music director of the Orange County Philharmonic Society, an orchestra dedicated to giving free concerts to audiences. Belinfante herself appeared as the featured soloist with the orchestra in the 1958-59 season, in Haydn’s Cello Concerto in C-major, and well-known artists were featured guest soloists. Sadly, her recordings have not been preserved. Her final recording included the Haydn Cello Concerto in D major and the Brahms Sonata in E minor for cello and piano.

Joseph Haydn: Cello Concerto No. 1 in C Major, Hob.VIIb:1 – I. Moderato (Marie-Elisabeth Hecker, cello; Kremerata Baltica)

As a cellist and viola da gamba player, Belinfante was drawn to the music of Johannes Brahms and Johann Sebastian Bach, especially the latter’s Suites for Solo Cello. Critics and audiences were impressed by her beautiful cello sound, flawless intonation, solid technique, and her deep musical interpretations.

As a cellist and viola da gamba player, Belinfante was drawn to the music of Johannes Brahms and Johann Sebastian Bach, especially the latter’s Suites for Solo Cello. Critics and audiences were impressed by her beautiful cello sound, flawless intonation, solid technique, and her deep musical interpretations.

Once again rumors circulated about her personal life and the world seemed not yet ready for a female conductor. In 1962 her contract was not renewed.

Eventually Belinfante’s heroism was recognized by the Dutch government. The first time she shared her experiences, when she was 90 years old, was in an extensive aural and video interview recorded by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Belinfante admits to her aversion about speaking of the dark moments of her life, the evil she saw in the human race, and how long it took her to be able to make music again. Her over 80-page complete testimony in the link below, although rambling at times, describes much more than is possible in just one article. Below is also a short film about her life—a resistance fighter whose story was suppressed due to her sexual orientation.

As a trailblazer for the arts, Orange County finally recognized her artistic achievements and designated February 19th as “Frieda Belinfante Day.” She moved to New Mexico in 1991 and passed away there four years later. A film But I Was a Girl—the Life of Frieda Belinfante was made in 1998—A truly extraordinary woman who showed what a difference an individual can make.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Belinfante short video interview

Defying Nazi Persecution: Freida, and Wilhelm

What an interesting, remarkable story. I don’t think I had ever heard of Belinfante before. How boring most of our lives are when hearing about hers.

Frieda Belinfante was my cello teacher from 1962 – 1967. A remarkable woman who became a close friend. She shared many incredible stories with me over the years.