When he went to the US in 1891 to become the head of the American Conservatory of Music in New York, Antonín Dvořák’s patron, Mrs. Jeannet Thurber, intended him to be the founder of not only the first conservatory in the US but also the founder of a national musical identity. It was this outsider from Bohemia that made American composers stop looking toward Europe for inspiration and look closer to home, at the negro spirituals and other native music sources that were to form the inspiration for so much American music in the 20th century.

Antonín Dvořák

Dvořák contributed by writing his American Quartet and the New World Symphony, using native music and even the music of the native songbirds as his inspiration.

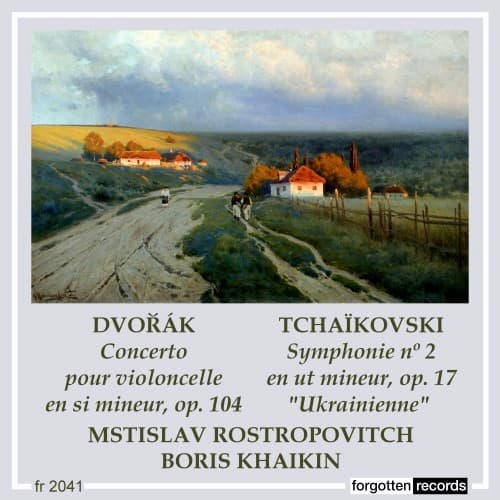

The Czech cellist Hanuš Wihan, one of the greatest cellists of his time, had been asking Dvořák for a concerto, but the composer was not fond of the cello as a solo instrument. He thought it perfect for orchestral music but found its high register to be too nasal and its bass to be mumbling. The middle register was fine, but not the outer registers. It was his view of the great Niagara Falls that he found his inspiration for his Cello Concerto, so the story goes.

He worked on the concerto from November 1894 to February 1895 in New York but did his revisions and created a new ending during the summer of 1895 while he was back in Bohemia. Originally intended to end in a positive mood, the concerto was rewritten in a darker tone after the death of Dvořák’s sister-in-law Josefina Čermáková. Dvořák removed the joyous coda and added a more meditative ending, written as a farewell to the woman who had been his sweetheart before marrying his brother. He said: ‘My finale closes gradually, diminuendo, like a sigh, with reminiscences of the first and second movements; the solo dies down to pianissimo, then swells again, and the last bars are taken up by the orchestra and the whole concludes in a stormy mood. This is my idea and I cannot depart from it!’

This was not how a Romantic concerto was supposed to end: there should be a grand virtuoso cadenza for the soloist but Dvořák was adamant that this not be added, saying to his publisher that if he allowed anyone to add such a cadenza, even Wihan, he would withdraw the work from publication. The work remains with his original melancholic, pensive ending. The work is also considered one of the best cello concertos in the repertoire.

Antonín Dvořák: Cello Concerto in B minor, Op. 104 – III. Finale

Mstislav Rostropovich

This recording was made in 1959 with the cellist Mstislav Rostropovich and conductor Boris Khaikin leading the Soviet Radio Symphony Orchestra. Mstislav Rostropovich (1927-2007) was both a cellist and conductor, considered by many to be the greatest cellist of the 20th century. His position led to the inspiring and commissioning of many new works, perhaps adding as many to the cello repertoire. In August 1968, Rostropovich was playing the Dvořák cello concerto with the Soviet State Symphony Orchestra at the London Proms; the same day Czechoslovakia was invaded to end the Prague Spring uprising. At the end, the orchestra and the soloist were cheered by the audience and Rostropovich held aloft Dvořák’s score to show his solidarity with the city of Prague and Dvořák’s homeland.

Performed by

Mstislav Rostropovitch

Boris Khaikin

Orchestre Symphonique de la Radio de l’URSS

Recorded in 1957

Official Website

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter