Considered “one of the finest studies of the psychopathology of guilt written in any language, Fydor Dostoevsky’s novel Crime and Punishment was first published in twelve monthly installments in 1866. The author had just returned from a 10-year exile in Siberia and he owed large sums of money to creditors. Trying to help the family of his brother Mikhail, he turned to the publisher Mikhail Katkov and offered his story for publication in the monthly journal The Russian Messenger.

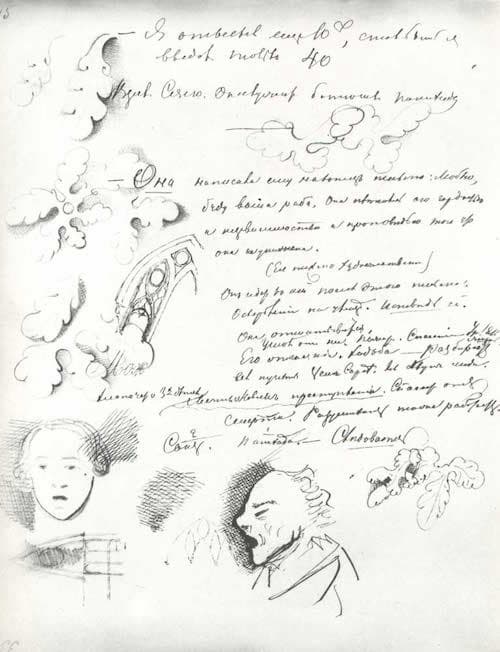

Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment manuscript

Dostoevsky explained that the work “was to be about a young man who yields to certain strange, unfinished ideas, yet floating in the air.” He planned to “explore the moral and psychological dangers of the ideology of radicalism.” Dostoevsky writes, “At the end of November much had been written and was ready; I burned it all; I can confess that now. I didn’t like it myself. A new form, a new plan excited me, and I started all over again.” The story became a novel and a project called The Drunkards became ancillary to the narrative of Crime and Punishment.

Arthur Honegger: Crime et Châtiment, “Générique” (Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra; Adriano, cond.)

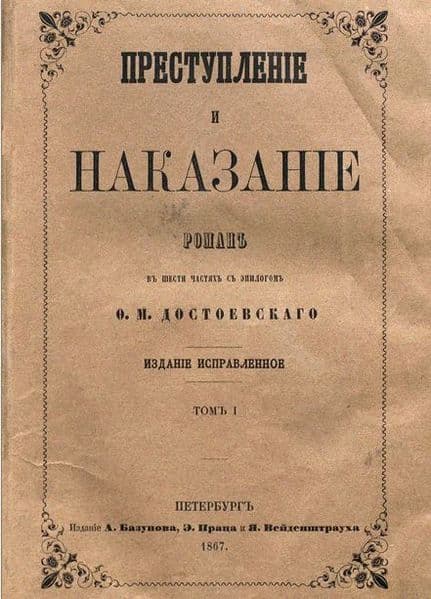

Cover of the first edition of Crime and Punishment, 1867

In Dostoyevsky’s novel, the former law student Raskolnikov lives in a filthy tiny room in St Petersburg in extreme poverty. Isolated and antisocial, he is obsessing on a scheme to murder and rob an elderly pawnbroker. Initially, he is unable to commit the crime and in a tavern he meets Marmeladov, a drunkard who recently squandered his family’s wealth. Marmeladov tells him about his teenage daughter, Sonya, who has become a prostitute in order to support the family. Raskolnikov subsequently receives a letter from his mother, describing a series of tragic events. In a state of extreme agitation, he steals an axe and makes his way to the pawnbroker. He gains access by pretending that he has something to pawn, and kills her with the axe. He also kills her half-sister Lizaveta, who accidently stumbled onto the scene. He steals only a couple of items and returns to his room undetected. Obsessed by the murder he has committed, he becomes involved with Sonia. Racked with confusion, paranoia, and disgust for his actions, his justifications for killing the pawnbroker disintegrate completely. He struggles with guilt and horror, and the more he feels attracted to Sonia, the more he feels the need to confess his crime to the police, who already suspect him but cannot prove his guilt.

Arthur Honegger: Crime et Châtiment, “Raskolnikov-Sonia” (Jacques Tchamkerten, ondes martenot; Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra; Adriano, cond.)

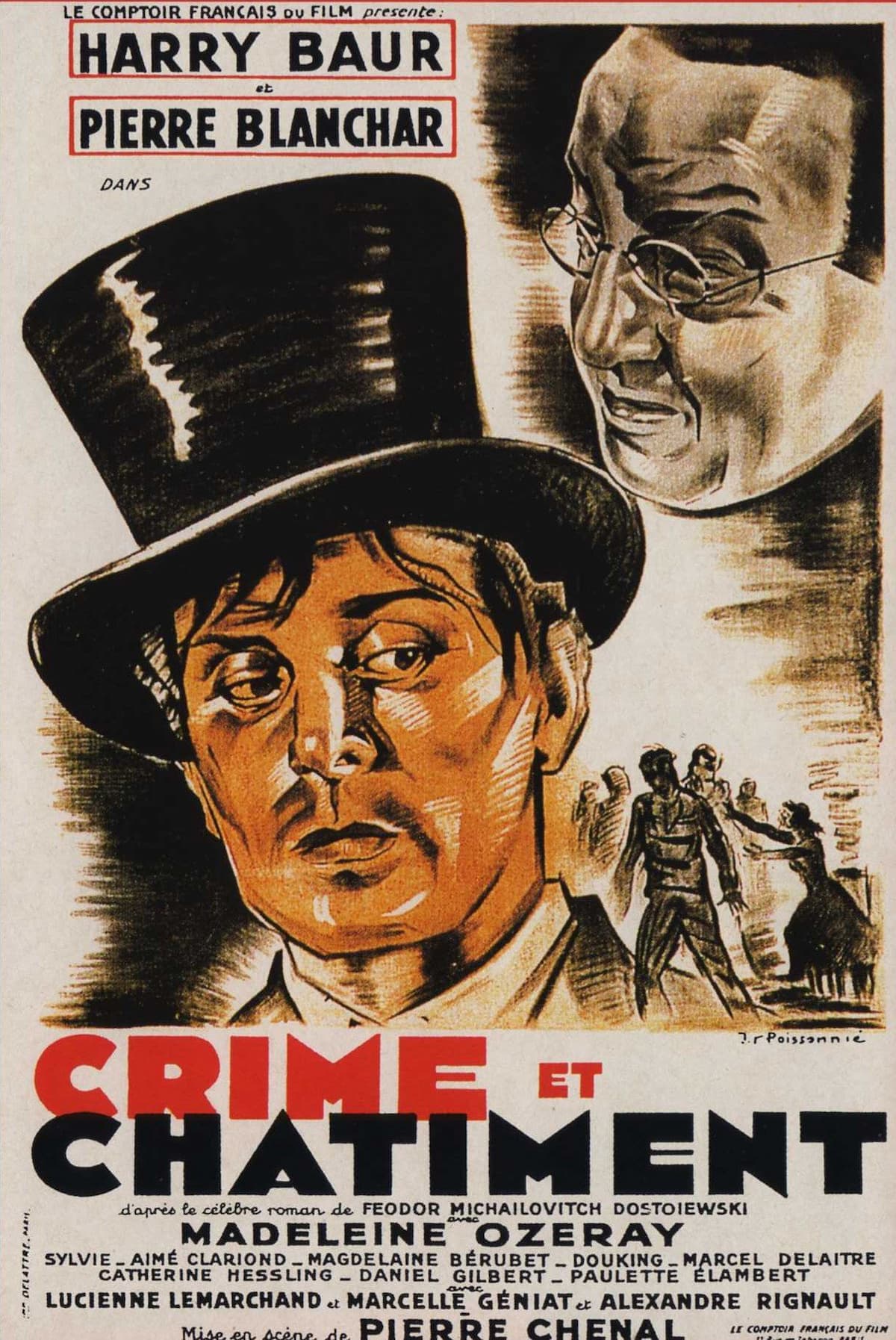

Crime and Punishment, 1935

Eventually, another man confesses to the murder; although Raskolnikov comes clean, he finally confesses to the crime and is sentenced to eight years in prison in Siberia. Sonya follows him but he is initially hostile towards her. He is still struggling to acknowledge moral culpability for his crime, feeling himself to be guilty only of weakness. “It is only after some time in prison that his redemption and moral regeneration begin under Sonya’s loving influence.” Crime and Punishment is frequently cited as one of the supreme achievements in literature and is considered one of Dostoevsky’s greatest works. It is hardly surprising that it has inspired well over 25 film adaptations, already starting in the early days of silent films. The French director and screenwriter Pierre Chenal, best known for his later “film noir’ thrillers, took on the Dostoevsky novel in the 1935 French crime drama film Crime et Châtiment.

Arthur Honegger: Crime et Châtiment, “Départ pour le crime” (Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra; Adriano, cond.)

Film poster of Crime and Punishment, 1935

Produced by Michel Kagansky, it starred Harry Baur as the humanist detective Porfiry, Pierre Blanchar as the sociopathic Raskolnikov, and Madeleine Ozeray as Sonja. Chenal engaged the French art director Aimé Bazin (1904-1984) to design the film sets but rejected the original designs as “too realistic and historically faithful.” Eventually, a more expressionist ambiance was created for the film. The music, in turn, was entrusted to Arthur Honegger (1892-1955). Member of “Les Six,” Honegger was a film enthusiast who was frequently seen on the set during shooting. For him, “cinematic montage differs from musical composition in that, while the latter depends on continuity and logical development, the film relies on contrasts. Music and sound must, therefore, adapt themselves to strengthening and complementing the visual element, while the whole must be an artistic unity, in which the generally visual imagination of the public may be assisted to a greater understanding of the musical message.”

Arthur Honegger: Crime et Châtiment, “Meurtre d’Elisabeth” (Jacques Tchamkerten, ondes martenot; Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra; Adriano, cond.)

Arthur Honegger

Honegger made a substantial contribution to film over the course of some thirty years. In all, he scored forty films, starting with Abel Gance’s silent epic La Roue in 1922. Honegger was lauded as “the true leader of modern film music in France in 1936,” as he regarded the ideal film score “as a distinct component in a unified medium.” In his music for Crime et Châtiment Honegger used the “Ondes Martenot” as a solo instrument “for leitmotifs, as re-enforcement of the bass-line, or as an atmospheric addition to the score.” The leitmotifs of Sonia and Raskolnikov are prominently heard in the second movement. Both are highly lyrical but “differentiated psychologically by their accompaniments.” “Départ pour le crime” is the longest movement in the suite, and it is intended to describe the psychological development rather than the physical action on the screen. “In both “Générique” and “Final,” a theme of Russian flavour is brought to a climax, with very unusual, almost uncanny orchestration.” Honegger explained, “In the case of film music, I need only to see the picture and start my work: the images are still fresh before my eyes. The closer the picture is to my memory, the easier my work is: the most important thing is to transcribe impressions that are still fresh, without delay.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Arthur Honegger: Crime et Châtiment, “Visite nocturne-Final” (Jacques Tchamkerten; ondes martenot; Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra; Adriano, cond.)