Nellie Melba

What do old opera singers do when they age out? The early 20th-century soprano Nellie Melba did a farewell tour and then another one and then another one, so much that Webster’s dictionary made a verb of it. ‘To do a Melba’ is ‘to make repeated farewell appearances.’ For other performers, they just take their love of the stage a little too far, stopping not at the height of their powers, but somewhere at the bottom of the unfortunate descent that follows.

Ezio Pinza and Mary Martin in the final scene from South Pacific

A few singers took their voices to new stages in their later years. Bass Ezio Pinza, for example, made his Met debut in 1926 and retired from that stage in 1948. He then took to the Broadway stage, and in April 1949, made his debut as the French planter Emile de Becque in Rodgers and Hammerstein’s South Pacific. This role earned him a Tony Award.

Rodgers: South Pacific: Some Enchanted Evening (Ezio Pinza, Emile de Becque; Original Broadway Cast Orchestra; Salvatore Sell’Isola, cond.)

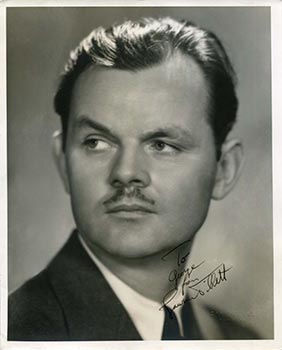

Baritone Lawrence Tibbett made his Met debut in 1923 and concluded his opera career in the 1950s. He also took to the stage, performing as Captain Hook in a production of Peter Pan with music by the young Leonard Bernstein. On Broadway, he replaced Ezio Pinza in Harold Rome’s musical Fanny.

Verdi: La Traviata: Act II Scene 1: Pura siccome un angelo (Lawrence Tibbett, Germont; Rosa Ponselle, Violetta; Metropolitan Opera Orchestra; Ettore Panizza, cond.)

Lawrence Tibbett

Tenor Lauritz Melchior (1890-1973) sang in 519 Wagner performances at the Met between 1926 and 1950, and overlapped this with appearing in 5 Hollywood films between 1944 and 1950. He then made a 19-week vaudeville appearance at the Palace Theatre in New York in 1952, following the model set by Judy Garland, where he appeared with eight other acts, such as Andre, Andree and Bonnie, “The Dancing Mannequins.” Billboard reported his rave reviews, but the theatre’s attempt at reviving vaudeville failed.

Wagner: Götterdammerung: Prologue: Willst du mir Minne schenken (Helen Traubel, Brünnhilde; Lauritz Melchior, Siegfried; NBC Symphony Orchestra; Arturo Toscanini, cond.)

Lauritz Melchior

Those were the successful opera singers who were able to extend their careers by moving to Broadway or Hollywood. Then there are the singers who never gave up soon enough, such as Rosa Ponselle.

Singer Rosa Ponselle (1897-1981) was one of the greatest sopranos of the 20th century, but a 1935 production of Carmen at the Met brought such blistering reviews from the critics that her final years were spent pursuing and singing roles with less-taxing high notes. As her voice faded, her ability to sing her signature roles also faded and she largely sang at home for her friends. Eventually, she took on the task of coaching for the startup Baltimore Civic Opera Company, where next-generation singers including Beverly Sills, Sherrill Milnes, and James Morris benefited from her work.

In this recording, taken from a live broadcast of May 1935, we can hear her making adjustments to avoid some of the now-out of reach top notes.

Verdi: La Traviata: Act I: Follies! Humor! – Always free (Rosa Ponselle, Violetta; Metropolitan Opera Orchestra; Ettore Panizza, cond.)

Rosa Ponselle

When we think of modern singers, who, unlike singers of the past, have their entire career following them on recordings, we see fewer and fewer extensive careers. Singers today also have large bands of internet followers who note their every triumph and disappointment, and do not hesitate to show their own erudition and taste (or lack thereof) in putting their criticisms online. Many opera singers now change from opera singing to singing with orchestras – but it isn’t always to the delight of the audience!