C.P.E. Bach (1714-1788), second surviving son of Johann Sebastian Bach and Maria Barbara Bach, was the true successor to his father’s legacy. Considered by his contemporaries as one of the most important composers and harpsichordists of their time, his enormous output has however been overshadowed by the resurrection of his father’s work in the early 19th century. Only in recent years have many of his works been rediscovered; many more await their first publication in modern editions and so their first performance in concert halls around the world. One reason for this neglect is the fact the music historians generally judged music of the Baroque and Classical periods superior to the style of the mid-18th century, which was considered insignificant and ‘transitional’. This musical style — which has been called in turn, ‘style gallant’, ‘Empfindsamkeit’ (‘sensibility’) and ‘Sturm und Drang’ (Storm and Surge) — emerged during the period known as ‘Rococo’ in art and architecture.

C.P.E. Bach (1714-1788), second surviving son of Johann Sebastian Bach and Maria Barbara Bach, was the true successor to his father’s legacy. Considered by his contemporaries as one of the most important composers and harpsichordists of their time, his enormous output has however been overshadowed by the resurrection of his father’s work in the early 19th century. Only in recent years have many of his works been rediscovered; many more await their first publication in modern editions and so their first performance in concert halls around the world. One reason for this neglect is the fact the music historians generally judged music of the Baroque and Classical periods superior to the style of the mid-18th century, which was considered insignificant and ‘transitional’. This musical style — which has been called in turn, ‘style gallant’, ‘Empfindsamkeit’ (‘sensibility’) and ‘Sturm und Drang’ (Storm and Surge) — emerged during the period known as ‘Rococo’ in art and architecture.

In architecture, ‘Rococo’ is considered the late phase of the Baroque. The term itself comes from the French ‘rocaille’ (shell), used in France in the decoration of palaces, garden grottos, etc. An early form of this style appeared during the latter part of the reign of Louis XIV (ruled 1643-1715), of which the Château de Marly is a perfect example, and came into full bloom during the reign of Louis XV (ruled 1715-1774). The Rococo style is generally considered lighter and more delicate, intimate and elegant than the Baroque. Decorative details are irregular and decorations echo the natural appearances of garlands of fruit, leaves, flowers and shells. Rather than the gilded, overly decorated interiors of the Baroque, pastel colors such as ivory, pale yellow, and light blue become the choice of Rococo architects. Important painters of the period, such as Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1732-1806) and François Boucher (1703- 1770), the favorite painter of Louis XV’s mistress, Madame de Pompadour, depicted members of the aristocracy in bucolic settings, engaged in romantic pursuits, dressed as shepherdesses and shepherds. Often the paintings were inserted into and occupied entire walls, rather than being displayed in frames, to give the illusion of the interior of rooms as settings in nature.

In architecture, ‘Rococo’ is considered the late phase of the Baroque. The term itself comes from the French ‘rocaille’ (shell), used in France in the decoration of palaces, garden grottos, etc. An early form of this style appeared during the latter part of the reign of Louis XIV (ruled 1643-1715), of which the Château de Marly is a perfect example, and came into full bloom during the reign of Louis XV (ruled 1715-1774). The Rococo style is generally considered lighter and more delicate, intimate and elegant than the Baroque. Decorative details are irregular and decorations echo the natural appearances of garlands of fruit, leaves, flowers and shells. Rather than the gilded, overly decorated interiors of the Baroque, pastel colors such as ivory, pale yellow, and light blue become the choice of Rococo architects. Important painters of the period, such as Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1732-1806) and François Boucher (1703- 1770), the favorite painter of Louis XV’s mistress, Madame de Pompadour, depicted members of the aristocracy in bucolic settings, engaged in romantic pursuits, dressed as shepherdesses and shepherds. Often the paintings were inserted into and occupied entire walls, rather than being displayed in frames, to give the illusion of the interior of rooms as settings in nature.

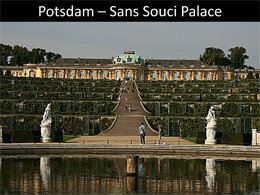

Sanssouci Palace, on the outskirts of Berlin in Potsdam, is representative of the Rococo style in Germany. Conceived as the summer palace of Frederick II of Prussia, better known as Frederick the Great (1712-1786), and based on Frederick’s own original drawings, Sanssouci was started and built as a single-story palace by the great architect Georg Wenzeslaus von Knobelsdorff between 1745 and 1747, and was finished by the Dutch architect, Jan Bouman. Here, Frederick the Great could relax (‘sans souci’ translates as ‘without worry, without care’) and hold his famous musical and dinner soirées in the circular Marble Hall of the Rotunda. Here, he received famous guests, such as Voltaire, Casanova, La Mettrie and many others. Elegant steps through terraced gardens, where grapes, figs and espaliered fruit trees were planted, lead to the south side of the palace, which rises above the terraces, seemingly one with nature.

Frederick II

Frederick II

Sinfonia in D Major

The king was an accomplished flutist and even composed symphonies and flute concerts, such as the ‘Concerto for Flute, Strings and Basso Continuo in G-major’ and the ‘Symphony for two Flutes, two Oboes, two Horns, Strings and Basso Continuo in D-major’, just to name two of many. The painting by Adolf von Menzel, ‘The Flute Concert’, shows Frederick the Great in the center, playing the flute. Set in the Marble Hall of Sanssouci Palace, the painting also shows C.P.E. Bach at the harpsichord (he had been appointed court harpsichordist in 1740) and Johann Joachim Quantz (1697-1773), composer and flute instructor to Frederick the Great, to the right of Bach, leaning toward the frame of the painting.

CPE Bach

Keyboard Sonata in F Major, Wq. 48/1, H. 24, “Prussian Sonata No. 1”

The harpsichord (called either ‘Clavier’ or ‘Cembalo’ in German and ‘clavecin’ in French) was Bach’s favorite instrument. He owned one of Georg Silbermann’s (Master Organ Builder, mentioned in my previous article on J. S. Bach) legendary harpsichords, probably a gift from his father when he left Leipzig to assume his position at Frederic’s court. C.P.E. Bach’s early major works all featured the harpsichord, such as the ‘Prussian Sonatas’, dedicated to Frederick the Great, which led him to the publication of one of his major theoretical works in 1753, “Versuch űber die wahre Art das Clavier zu spielen” (Essay on the true manner in which to play the harpsichord). Musically, we can hear the shift from the more ‘serious’ polyphonic style of his father, J. S. Bach, to a more ‘gallant style’ expressed in his statement “Mich deucht, die Musik műsse vornehmlich das Herz rűhren” (“It seems to me that music above all has to touch the heart”). Feelings, melodic lines and a new ‘cantabile’, perhaps stemming from Italian influences such as Vivaldi and Scarlatti, make an appearance. A new freedom from conventional rhetorical norms such as counterpoint, leads to different musical concepts in which unusual, sudden stops, interruptions, different harmonies, more expressive musical lines, as well as puns and light-hearted subjects (such as C.P.E. Bach’s composition “Farewell to my Silbermann Clavier”) and songs in the folksong tradition, such in his ‘Der Wirt und die Gäste’ (The innkeeper and the patrons), become the norm. C.P.E. Bach is here well ahead of the developing German literary traditions of the same era — those of Klopstock, Herder and the young Goethe (‘The Sorrows of Young Werther’) — which were the precursors of the ‘classical’ and ‘romantic’ literary traditions.

The harpsichord (called either ‘Clavier’ or ‘Cembalo’ in German and ‘clavecin’ in French) was Bach’s favorite instrument. He owned one of Georg Silbermann’s (Master Organ Builder, mentioned in my previous article on J. S. Bach) legendary harpsichords, probably a gift from his father when he left Leipzig to assume his position at Frederic’s court. C.P.E. Bach’s early major works all featured the harpsichord, such as the ‘Prussian Sonatas’, dedicated to Frederick the Great, which led him to the publication of one of his major theoretical works in 1753, “Versuch űber die wahre Art das Clavier zu spielen” (Essay on the true manner in which to play the harpsichord). Musically, we can hear the shift from the more ‘serious’ polyphonic style of his father, J. S. Bach, to a more ‘gallant style’ expressed in his statement “Mich deucht, die Musik műsse vornehmlich das Herz rűhren” (“It seems to me that music above all has to touch the heart”). Feelings, melodic lines and a new ‘cantabile’, perhaps stemming from Italian influences such as Vivaldi and Scarlatti, make an appearance. A new freedom from conventional rhetorical norms such as counterpoint, leads to different musical concepts in which unusual, sudden stops, interruptions, different harmonies, more expressive musical lines, as well as puns and light-hearted subjects (such as C.P.E. Bach’s composition “Farewell to my Silbermann Clavier”) and songs in the folksong tradition, such in his ‘Der Wirt und die Gäste’ (The innkeeper and the patrons), become the norm. C.P.E. Bach is here well ahead of the developing German literary traditions of the same era — those of Klopstock, Herder and the young Goethe (‘The Sorrows of Young Werther’) — which were the precursors of the ‘classical’ and ‘romantic’ literary traditions.

Many of C.P.E. Bach’s works should not be underestimated — they deserve re-evaluation in order to find their rightful place in the history of music in the 18th century.

More Arts

- Alexandre Dumas (1802-1870)

“Music is the only noise for which one is obliged to pay” We look at his collaborations with composers on operas and more! - “In the Hall of the Mountain King”

Henrik Ibsen in Music "Peer Gynt goes very slowly. It is a horribly intractable subject except for a few places… " - Edgar Degas (1834-1917)

“No art could be less spontaneous than mine” Look at Degas' burning passion for opera from his artwork - Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669)

Born on 15 July Learn about his ancestry, childhood and more